FEATURE

In a Midwestern studio this fall, a likeness of President Charles W. Steger awaited John Boyd Martin, the renowned painter who has done the portraits of the past three Virginia Tech presidents.

To the artist, the image—a painting study—represents the sum of his impressions from a spring visit to Blacksburg. Martin dined with Steger, observing the president's mannerisms and personality. He shot black-and-white photos and then conducted the painting study, a two- to three-hour sitting that helped him record skin tones.

"Being around them [portrait subjects] is how you bring out the personality," Martin said in his studio in Overland Park, Kan. "We did the sitting at his home, and I felt very comfortable. I think he has a down-to-earth quality that was resonating."

When asked what he saw in Steger's personality, Martin pointed to the painting study. "That image tells you somewhat because of the thoughtful look," he said, adding that he found Steger to be very much "at ease, very relaxed," articulate, and well-versed on student and university concerns.

It will take Martin an estimated one month of eight- to 12-hour days to complete the life-size painting that will one day be displayed in Burruss Hall, thus preserving the legacy of Charles W. Steger at Virginia Tech.

On a much larger canvas, with much broader strokes, Virginia Tech's 15th president has brilliantly colored the campus, the commonwealth, and the globe.

At his inauguration in April 2000, Steger outlined a bold vision. He pledged to focus on research, economic development and outreach, partnerships with other universities and the private sector, innovations in information technology, and more. He challenged the university to rank among the top 30 research universities in America, increase enrollment and diversity, address critical space needs, enhance the arts, significantly increase private giving, and recruit the best and brightest students as ways to stimulate the entire academic enterprise.

In May, the president announced his intention to step down. The search for his successor is under way, and Steger will stay on board until a new president takes office. Taking stock of his tenure, one could almost call his 2000 speech prophetic. Virginia Tech's architect of growth, Steger has achieved the majority of his goals through a rare ability to exhibit both the artistic touch to craft a vision and the pragmatic know-how to implement it, along with an aptitude to spot and interpret trends well ahead of others and empower a dedicated leadership team to help him position the university on the right trajectory.

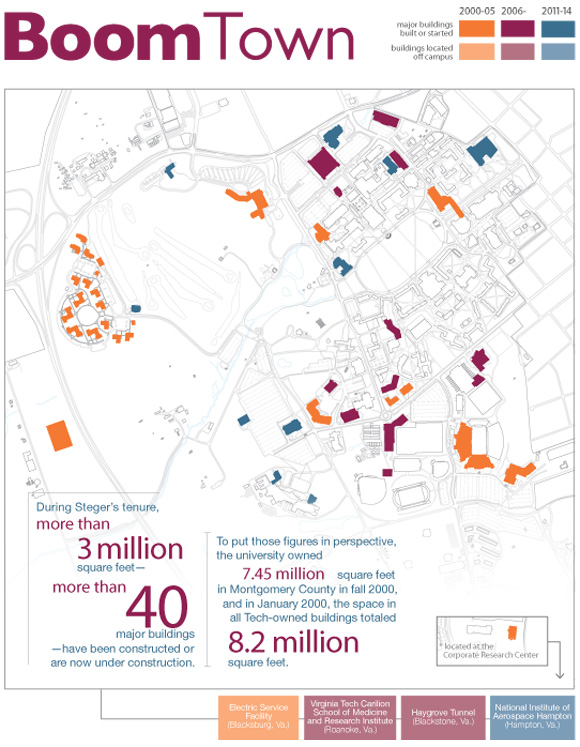

Since 2000, Virginia Tech has increased its total research expenditures from $192 million to more than $450 million, increased graduate enrollment by 12 percent, raised more than $1 billion in private funding, finished or started building more than 3 million square feet of space, formed a school of biomedical engineering and a school of medicine, and much more. The university has exported its excellence out of Blacksburg, expanding its presence in Roanoke, Southside Virginia, Northern Virginia, Europe, Asia, and elsewhere.

"I think [Steger] has provided visionary leadership," said T. Marshall Hahn Jr., Virginia Tech's president from 1962 to 1974. "You could tick off just a number of things and hardly scratch the surface. He's driven the university forward on all fronts."

The notion of accelerated growth was launched in 2000 by Steger's stated emphasis on research. "When he became president, the single most powerful and effective thing he did was to raise the bar in terms of the top-30 rhetoric," said University Distinguished Professor and Senior Fellow for International Advancement Paul Knox, the College of Architecture and Urban Studies (CAUS) dean from 1997 to 2006. "That is a simple strategy or tactic, but it really thoroughly ran through the whole university."

"One of the things that [Steger] never lost sight of is if we want the university to grow to a higher level of distinction, then incremental growth is not going to be sufficient," said Virginia Tech Provost Mark McNamee, hired by Steger in 2001. "We thought in terms of big leaps forward. And I think Charles' legacy is going to be defined by those big, giant steps."

Steger knew that Virginia Tech couldn't accelerate its position as a major university by chasing the the likes of Harvard. "Instead of climbing the ladder, I view it as a pole-vaulter. You've got to have a pole that's got some flex in it and some elasticity and some potential energy that flips you over the bar. You can't get there by playing the existing game. You have to create the new environment," Steger said in an interview in August.

The strategy to achieve such an audacious vision—one of giant steps and new environments—arose from a mind uniquely suited to the university presidency, from a man of international standing who puts students at ease, from a man who renders the complex simple and inspires the talent around him. What's more, this architect-president—a three-time alumnus with bachelor's and master's degrees in architecture and a Ph.D. in environmental engineering and sciences—was laboring on behalf of his alma mater.

Steger's architectural training has served him well. An architect in the early phases of design deals with complex problems with many variables, some unquantifiable. "It requires a level of creativity, a development of other areas of the intellect for complex problem-solving and pattern recognition, basically, and then a sense of judgment of aesthetics," Steger said. "And I don't mean it just in terms of what one thinks is pretty, but in terms of efficiency and economy and beauty and all these things at the same time, in the same way that a mathematical equation can be aesthetically pleasing. You solve the problem in a way that's most efficient and most elegant."

When retiring Clemson University President James F. Barker accepted the dean's post in Clemson's College of Architecture in 1986, he sought out the advice of Virginia Tech's then-CAUS dean, Charles Steger. "I've observed that an architectural education is not deep, but it is wide," Barker said. "That kind of wide thinking is what a president's job requires. You must lead teams of creative people to make connections and solve problems. Charles Steger has excelled in this role."

"People in [architecture] … understand and can see patterns of things—whether it's patterns of opportunity [or] patterns of design in a building. It's part of the DNA. And [Steger] has that—to be able to see patterns, to connect the dots that other people maybe can't see as easily," said Jim Bohland, professor emeritus of urban affairs and planning in the School of Public and International Affairs and the interim vice president and executive director of National Capital Region (NCR) Operations.

After finishing his master's degree, Steger joined Wiley and Wilson, an architectural and engineering firm in Lynchburg, Va., where his capacity for planning—and overall skill—was quickly recognized. In his mid-20s, he was placed in charge of the firm's urban-planning division.

Meanwhile, the last-minute departure of a faculty member at Virginia Tech opened a spot for Steger as a visiting lecturer in 1973-74. As he also managed an environmental impact study on a highway relocation for Wiley and Wilson, with 13 Ph.D.-level consultants evaluating everything from noise radiation to sedimentary build-up in streams, Steger recognized the ecological movement's emergence and that he needed a doctorate to become a better architect and planner.

As Steger studied for a Ph.D. in environmental engineering and sciences and taught in CAUS, Wiley and Wilson wasn't ready to let him go. The firm continued to pay him the same salary, minus the work duties, and iced the cake with an IBM Selectric typewriter and a year-end bonus. But Steger, hooked on the academic environment, opted to stay on at Tech. By 1976, when he was in his late 20s, he was named chair of the urban-design graduate program.

A short time later, Charles Burchard, founding dean of CAUS, who had decided to retire, was walking across the Drillfield with then-Provost John Wilson. Said Steger, "He asked Burchard, 'Is there anyone in the college you think should succeed you as the dean?' And so Burchard gave him my name. Wilson later told me, many years later, 'I thought the man had lost his mind.'" Steger was a candidate that time around and wasn't chosen, but the position soon opened up again—and at the age of 33, Steger became the youngest dean of an architecture school in the nation.

The new dean took care to understand the pedagogy of the college and to preserve the essence of Burchard's legacy. "You had to be the guardian of those key things," he said, "so that's what I tried to do."

Steger intuitively grasped how the college could participate in the university's growth, and the college's research program tripled, becoming one of largest in the nation. Said Knox, "I remember when I first came to the college [in 1985]. [Steger] was dean and drew a small number of us aside because, even back then in the mid-80s, he was aware that the university … was going to be having to rely more on externally funded research. And that was our charge … to increase that as fast as we could."

Steger was already thinking boldly. Building upon the university's land-grant mission, Steger, as dean, established an architectural presence in Northern Virginia. The Washington-Alexandria Architecture Center now encompasses five buildings and hosts an international consortium of architecture schools.

"[The center] was impressive. That was entirely Charles' doing," said David Roselle, Virginia Tech's provost from 1983 to 1987, who later served as president of the University of Kentucky and the University of Delaware. "When he became dean, there was no real concern about that aspect of architectural education. He saw it, he designed a solution, [and] it was pretty bold for the time." Added Roselle, the center was "a precursor of what he's done, locating people away from Blacksburg and in other parts of the state."

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Steger, who as student-body president at Henrico County High School in Richmond, Va., had brought the first-ever international student to the school, would later internationalize his collegiate alma mater.

In Riva San Vitale, Switzerland, Virginia Tech's Center for European Studies and Architecture was once a study-abroad program led by Olivio Ferrari, an Alumni Distinguished Professor and a masterful design teacher, Steger said. Recognizing that Ferrari was irreplaceable and that the program needed a permanent facility, Steger started the process to acquire a building. "Believing in the value of this international study, I wanted to institutionalize the international study dimension by having a facility," Steger said. "I wanted to own something and not have it rented or leased, because I wanted it to be permanent."

Steger's philosophy of planting the Tech flag beyond Blacksburg is partially pinned to perception. "Without these other dimensions, we would be perceived as being parochial in a way," he said. "And so this provides an opportunity for our students to work and travel and have internships all over the world. It really adds another set of dimensions to the educational experience for the student. It also raises our visibility tremendously."

In the Ag Quad in August, Steger posed for the first of a series of photos for the magazine. The overcast afternoon was sweltering, but Steger wore a suit and tie. "It's my uniform," he said.

Donning the uniform as the public face of Virginia Tech, its primary lobbyist, is one of Steger's most critical functions—and he excels, according to Ralph Byers, executive director of government relations. "The fact is, if you're president of a major state university, just about anything that happens can become a political issue," Byers said. "And [Steger] is very attuned to that and has maintained his relationships with successive governors and state legislators, members of Congress, senators, representatives. … It's a tremendous job, and he has never let up."

The relationships with lawmakers are based on trust, said Steger, drawing an example from his meetings with former U.S. Sen. John Warner. The chairman of powerful committees would have 10 aides in the room, all of whom already knew what Steger would request. "If Warner gave the nod, it happened. If he didn't give the nod, it didn't happen. And it was my job to get him to nod in the right direction," Steger said. "And a lot of it is that confidence in the university—Virginia Tech is very highly regarded by these people—and the fact that they trust you. It's the institution, but there's also a personal side to this that you can't underestimate."

Steger understands the personal side well. Warner, as a young man, spent his summers working on a farm owned by a family full of Hokies, and Steger knew of the affection Warner had for the university. When other presidents might tend to press him for money, Warner said, his conversations with Steger centered on agriculture, football, and mining. "I always looked forward to his visits," said Warner, who served in the Virginia Senate post from 1979 to 2009. "I've never questioned his veracity ever. Ever."

State Sen. John Watkins (horticulture '69), who served as a state representative from 1982 to 1998 before his election to the Senate, said that Steger always took the time to listen. "And he's done his homework. He's not over the top, but he doesn't leave you with a lot of questions," Watkins said.

"One reason [Steger] has the respect he does is that he's always so modest and self-effacing," Byers said. "Especially since he's from Virginia, his style is something that fits very naturally with the political culture of the state. He just instinctively understands how to deal with different types of people in different situations. ... He makes it seem easy, but it's a very tough thing to do."

The journey has not always been smooth, however. In fall 2010, Virginia Cooperative Extension (VCE) responded to a General Assembly request to reduce costs, yet maintain a local presence throughout the commonwealth. The proposed restructuring plan came under fire as the public and lawmakers debated which offices to cut and how scarce resources should be allocated. Steger, as agency head, bore the brunt of displeasure toward VCE's plan to meet the legislatively mandated budget cuts. In consultation with legislators and constituents, he decided to withdraw the plan and go back to the drawing board. A dynamic, new Extension director was hired, and funding was restored by the General Assembly. Today, Extension is thriving, with more agents across the state than have been seen in many years.

Largely, however, the relationship equity that Steger built up with lawmakers paved the way for beneficial ventures, particularly the public-private partnerships that he set out to achieve in his inauguration speech. The plan to form the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute was announced in early 2007, and the first class of medical students started in fall 2010. "That was a decision that evolved very quickly and could've been stalled at any point. It was not the typical thing universities did," said McNamee, who added that Steger's clear vision and focus carried the project through.

In true land-grant fashion, the medical school and research institute aren't powering only Virginia Tech forward. Both are a "major game changer for Roanoke," said John Dooley, the former vice president for Outreach and International Affairs who is now the Virginia Tech Foundation's CEO. "It's going to position [Roanoke leaders] to be able to develop a new and different economic strategy that better leverages the health resources there, but also attracts entrepreneurs to the area."

Early in his presidency, Steger became a leader of the commonwealth's Council of Presidents, where he represented the interests of both Tech and Virginia's higher-education community. Nationally and internationally, Steger was able to offer learned wisdom to other presidents without being "arrogant or aloof, which can happen with such a large, dynamic university," said Linwood Rose (economics '73), James Madison University president from 1998 to 2012. "I think that's his real legacy. … So often, Charles would certainly be looking out for his institution, but would have a statesman's hat on and look out for the other institutions and how they could be involved."

Under Steger's leadership, Virginia Tech partnered with the University of Virginia (U.Va.) and the College of William & Mary to persuade state lawmakers to approve the Restructured Higher Education Financial and Administrative Operations Act in 2005. The act gave the university greater flexibility in capital outlay and new construction, long-range planning, revenue streams, personnel, purchasing, information technology, and other administrative areas.

John Casteen, U.Va. president from 1990 to 2010, credited much of the restructuring effort's efficiency to Steger, explaining that Steger was able to carry the torch for Virginia's higher-education community. "Good presidents are never cowboys," he said, referring to Steger's ability to collaborate and share the podium with others.

"One of the great qualities that Charles has is he has great foresight," said Dooley. "He can, to some degree, predict opportunities five, even 10 years out. He's got this uncanny way to look at what is, but also project what could or should be. He's always doing that."

With Steger, substantive action follows those predictions. Cognizant of the federal government's trend toward funding large multidisciplinary grants rather than individual projects, Virginia Tech shifted toward cross-cutting initiatives using a business model that invested in seven large research institutes. The institutes' managerial structure allowed the university to compete for and win larger research awards while also focusing resources in areas of strength so that the university could complete globally for the best and brightest minds.

With the likes of the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute (VBI), the university was also responding to shifts in how the federal government prioritized research spending toward, for instance, life sciences. Founded in 2000, VBI now employs more than 250 faculty and staff and has amassed more than in $100 million in research projects.

The institutes are an important part of why Tech's research funding has skyrocketed. And even if the notion of becoming a top-30 institution wasn't reached, the ambition yielded substantial results. "The significant part is that we've moved one heck of a long way from where we would have moved had we not had such a goal," said Ray Smoot (English '69, M.S. education administration '71), a long-time administrator and former CEO of the Virginia Tech Foundation. Smoot also pointed out the benefits associated with the research component—graduate placement rates, corporate philanthropy, and university reputation.

Another critical trend Steger detected was that major research institutions would get bigger—and he knew that Virginia Tech could not be left behind. In the "bimodal distribution of institutions," Steger said, "the strong major institutions are getting stronger at an accelerating rate. … The resources are flowing to those institutions. … If you have one machine that costs $750,000 that someone in electrical engineering needs, they can't do half their work for [half of that]. They don't do it all. It's like the rocket. Either you reach the speed to get into orbit or you don't get there; you crash. And so that's why we had to grow. That was part of the reason for the emphasis on research. We had to grow the critical mass of capital that we could invest in the future of the institution. We still need to grow the enterprise. I'd like to see us get to about $600 million [in research], and I think we will over time."

The grand goals in the 2000 inauguration speech grew out of Steger's ability to crystallize and articulate a vision and then draw others into the plan. Indeed, the seeds of ideas planted during his career would be nurtured by the talent around him.

After a three-year stint as acting vice president of public service, a role he held concurrently with the dean's post, Steger was named vice president for development and university relations in 1993. As he led the university from the perspective of fundraiser-in-chief, Steger further considered how to advance the institution. By the time he was named president in late 1999, he was more than ready to outline his strategy.

"I'd been thinking about [the goals] for a long time," said Steger, who, as a dean, had chaired the university's strategic planning committee. "When … I met with the [presidential] search committee, I said, ‘If you choose me, this is what I'm going to do, and it's going to be a very aggressive program.' And so they said, ‘Okay.'"

Soon after taking office, the president met with key administrators and Board of Visitors (BOV) members to map out the university's path forward. According to those who have worked with him for decades, Steger sets broad parameters and then steps back to let his team enact the plan. "I'd give him high marks in understanding this, the importance of having a solid team and engaging that team in the process," said Minnis Ridenour, who was executive vice president when Steger took office. "And that was one of the pleasures I had of working with Charles … being part of his team and feeling like you really were empowered."

"He set expectations and did not meddle as long as he felt his senior management team was working to make significant things happen," Smoot added.

Current BOV Rector Michael Quillen (civil engineering '70, M.S. '71) marveled at the audiences a president must satisfy, from athletic and elected leaders to physical-plant personnel and fundraisers. "There are a lot of different constituents that see things so differently, but the president is required to manage all of those, so it's a very complex job, similar to being CEO of a major corporation," Quillen said. "Just managing all of that has been the thing that has impressed me about Charles the most."

Steger's unpretentious personality may just be disguising a brilliant intellect. Serving on the CAUS advisory committee, G.T. Ward (building design '51, M.S. architecture '52) got to know the dean well in the 1980s. "Even then, [Steger] knew a lot about every major, every curriculum, every college," Ward said. "He's able to converse with anyone on campus about almost any intellectual [subject]."

In 2000, Stephan Bieri was the CEO and vice president of the board for the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, an educational system that partnered with Virginia Tech and the World Bank to create the World Institute for Disaster Risk Management (DRM) and conduct research on mitigating global natural disasters.

By way of DRM and also VBI—whose scientific advisory board Bieri chairs—Bieri came to appreciate Steger's intellectual capacity and academic vision as the two men explored topics with faculty members. "He wasn't just swimming on the surface, but [was] deep into the problem," Bieri said. "You cannot have such a job as [Steger] has had without the intellectual capacity yourself. This is not only a management job. Virginia Tech has an intellectual person of great analytical depth as the leader."

Even so, said McNamee, "He's very modest about his ideas. He'll sometimes preface and say, ‘This may be the worst idea in the world, but I've been thinking about X.' And it's actually a pretty good idea."

It's in Steger's nature to put people at ease. "He was able to make [people] feel good when [they] went to his office—he still does," Knox said. "One of those notorious things about President Steger is that he puts people at ease. There's a phrase, ‘He can walk with commoners and talk with kings.' He's that kind of person."

As a high school student-body president, Steger learned to tailor his messages for the ages of his various audiences. Even today, he connects well with students. Brian Montgomery (industrial and systems engineering '03), the 2001-02 Student Government Association president and a 2002-03 BOV representative, recalled how Steger encouraged him and other students to move ahead with their bold ideas—Relay For Life, the Big Event, and Hokies United. "It would've been much tougher to get those events off the ground without his support," Montgomery said. "For both the Big Event and Relay For Life, he came out in the pouring rain during the first year to support them."

Steger's rapport with alumni is similar, said Montgomery, who now serves on the Alumni Association Board of Directors. "His level of engagement and dedication and ability to network is second to none. He makes a lot of alumni feel connected to the university still today."

A sunny outlook despite the rain may characterize Steger best. "He has this sense of optimism about the future, and I think that colors his way of looking at a situation or creating a goal that's really achievable," said Tom Tillar, Class of 1969 (biological sciences '70, M.A. student personnel services '73, Ed.D. '78), the vice president for alumni relations. "He's never one to ignore challenges or perhaps the downside of trying something, but he is one who can see more clearly than anyone I've known at Virginia Tech that something can be achieved."

In the dark days and months following the tragedy of April 16, 2007, Steger's steady hand of leadership and his personal resolve inspired the university to pull together and recover.

Casteen, the former U.Va. president, commended Steger's statesmanlike, kind, and thoughtful response to the unprecedented event and found especially striking the "self-control and selflessness" that Steger and his team exhibited. "I remember wondering whether we would have the grace and the wisdom in a hard time to do the same," Casteen said.

Said Smoot, "The way he was able to keep this university together—students, faculty, staff, alumni—and continue at the same time, after a momentary pause, to advance the programmatic agenda … is absolutely incredible to me. To me, that is just real leadership that you don't often see."

In special remarks at the May 2007 Commencement, Steger shared one of the thousands of messages of sympathy and condolences the university had received: "Your loss is great, but your goal is our children's future." Continuing, he told the crowd, "How can we not be resolute and determined to go forward when we are reminded so poignantly—and by so many—of why Virginia Tech is here and what it stands for?"

"I think it was critical that we had this sense of community and [that] great affection for the institution was well entrenched before the tragedy occurred," Steger said in August. "And there's a lesson there in terms of how you manage relationships, whether with the town or whatever else or business problems. If you don't have a relationship before the problem, you can't build it after the problem occurs."

Steger recalled the days and weeks after the tragedy, sleeping only a couple hours a night and being escorted everywhere by security guards. When he speaks annually to business students at a management symposium, he emphasizes the lifelong process of developing values. "You work on it your whole life. But you have to start. You have to start today," Steger said. "When these types of very trying circumstances emerge, that's when you really have to look into yourself and know what you believe and have the internal strength to survive."

A hallmark of Steger's legacy is the way in which he has deepened the definition of the modern land-grant university, increasingly utilizing the university's intellectual capital to generate economic development as a way to meet society's needs. As corporate research and development funding shifts toward development alone, research—the discovery and pursuit of knowledge—is increasingly the domain of the university. The new model of innovation, then, is "combining the fruits of academic research with the spirit of entrepreneurism into commercial ventures that create new jobs," Steger wrote in a white paper on the subject.

The concept is uniquely embodied in the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research (IALR). Not long after Steger had been named president, a group of business and community leaders from Danville, Va., approached him. Long dependent on the declining tobacco and textile industries, the Southside region was struggling, and the group hoped Virginia Tech could help jumpstart the economy.

Ben Davenport (business administration '64), a former BOV rector, was part of that team of civic leaders. "I met with him one-on-one," said Davenport. "I never will forget; I went in there believing he was going to say no. He said, ‘I feel that Virginia Tech, as a land-grant university, needs to do what we can to help the different economies in Virginia, especially those that are in dire need.'"

Today, in large part because of IALR, the economy in Southside Virginia has found new life, attracting such companies as IKEA and General Motors. "As much as anything, it's made an impact to win people's minds and souls back in the region. Many of them felt downcast, but now they're feeling much more hopeful about the region," Davenport said.

"Charles has been a significant contributor at the national level in helping define what a contemporary land-grant university should be," said Dooley. "[IALR] is part of that. ... It contributes to the local region and leverages the unique assets of the university to help that region."

The same model applied to another region with entirely different circumstances: Northern Virginia, a hub for technology research, especially in fields such as cybersecurity and national security. Steger and others wanted to connect Tech's research capabilities to private and public sector organizations. Now, the Virginia Tech Research Center — Arlington, completed in 2011 and located in the city's Ballston district, operates near federal science and research agencies and private-sector technology companies. "[The center] enhances our ability to be a key player in research and development as a whole for the state," said Bohland. "We've helped the state develop a major presence in cybersecurity that it did not have before."

On campus, the Corporate Research Center (CRC) is expanding to double its square footage, and the university is exploring a research park in Newport News. "[Steger's] fingerprints are on the desire of the university to be more relevant to all the people in the state of Virginia, not just what goes on in Blacksburg," said CRC president Joe Meredith (aerospace engineering '69, Ph.D. industrial and systems engineering '97).

Deborah Wince-Smith is president and CEO of the Council on Competitiveness, a national coalition of CEOs, university presidents, and labor union leaders that pursues policy solutions to enhance U.S. competiveness in the global marketplace. She cited Steger's role in bringing a Rolls-Royce aerospace facility to Virginia as a model for the country in how collaboration allows both the "industry and [the] university [to] derive value for their core missions," while also spotting the same level of innovation in Tech classrooms. "Not only has the university really developed 21st-century oriented curricula, but [it] has linked their research capabilities into the education of undergraduates," she said. "[Steger is] not just a promulgator of next-generation thought, but a leader who has a capacity to implement [a vision] and show that these ideas work."

Casteen worked alongside Steger in a global collection of university heads, government officials, and corporate and foundation CEOs who meet periodically at Windsor Castle in England for the purpose of acting on significant issues. There and in other arenas—whether in Switzerland or in India, where Tech is now launching a campus with a substantial research presence—Steger has sought to engage Virginia Tech's experts in addressing global problems.

"Charles had no doubt that the world was moving toward a global arrangement and the university needed to expand out from Blacksburg," said Jaan Holt (architecture '64), who has directed the Alexandria architecture center since Steger appointed him to the role in the '80s.

Said Steger, "There are many nodes of innovation around the world, and you have to be plugged into them to stay ahead of the curve. And I want to institutionalize this."

Given the revolution in communications and information technology, the game has changed. "As a result of that, to be a major institution the standard of quality changes," Steger said. "It's not who's the best engineering school in Virginia. Nobody cares. The question is, who's the best in the world?"

"The whole effort [of outward expansion] was basically predicated on the notion that universities in the next 10 to 15 years are going to have to behave differently," Bohland said. "They can't be insular—they can't be just a residential campus. They've got to look at where the centers of excellence are in terms of innovation."

Born in 1947 in Richmond, Steger, the oldest child, has two sisters and a brother. His father worked for C&O Railroad, now part of CSX. Coming to college, Steger and other members of the Class of 1969 set foot on a campus inspired by growth. (Perhaps it comes as no surprise that so many of Steger's colleagues at the university came from the much-heralded class.)

"We came here when Marshall Hahn was about three years into his presidency, and the excitement that he had created—about expanding the size, the array of academic offerings, the athletic program, [and] the engagement within the state … was large," said Smoot. "Charles and I—and many, if not most, others—got caught up in that excitement. Everything [Steger] has done over the last 40 years is related to making significant and good things happen for Virginia Tech. He enjoys seeing significant things happen."

Tillar and Steger met each other in the first week or so. Their small group of friends, living on the same floor of Vawter Hall, dined together, laughed together, and secured rooms closer to each other in their sophomore year. "There was something unique about Charles that struck me then," Tillar said. "He had a great wit. He could talk on any subject, broadly educated.'"

As enrollment mushroomed with an influx of baby boomers, the campus expanded to keep up with the demand. "We saw the campus as a place under construction," Tillar said. "Just over from where our residence hall was, there were two dorms under construction, O'Shaughnessy and Lee. Lane Stadium was under construction. Virginia Tech to us represented this growing institution that was offering a lot of opportunities for students to come to college."

In the architecture college, created in 1964, Steger found himself face-to-face with Dean Burchard and other faculty members. Burchard had studied under the founder of the Bauhaus movement, which transformed the field and "defined a whole new path in architectural design," Steger said. "When I came, I didn't realize that I was lucky enough to arrive in a sort of golden age. … [The] period was extraordinary in terms of the level of innovation in architectural education."

As Steger completed his bachelor's and master's degrees, his high school sweetheart, Janet—one year behind him academically—transferred to Virginia Tech for her senior year, earning a bachelor's in art in 1970. The couple married in September 1969.

Known as "Crane City" during Hahn's tenure in the '60s and early '70s, the university has expanded even more under Steger. In fact, the campus footprint has grown more in Steger's 14 years than in the entire period from 1872 to 1960. During Steger's tenure, 40 major buildings totaling more than 3 million square feet have been constructed or are now under construction.

Continuous construction, of course, can't happen without funding, and the president brought his background in raising private funds to Burruss Hall. The Signature Engineering Building is a prime example of how Steger and his team have leveraged philanthropy to take big leaps.

"The resources needed to propel the university in the direction we want are not provided by the state—not just the issue of quantity, but also in terms of flexibility," Steger said. "I'd say virtually every innovative thing we do builds upon our private financial basis."

In the equation of capital construction, philanthropy has a multiplying effect. Seeking state support, the university proposed splitting the engineering building's cost 50-50. "That's a very powerful tool," Steger said.

Donations also beget other donations. "These are coupled equations," said College of Engineering Dean Richard Benson. "In other words, the willingness of alumni, friends, and others to come forward in support of a project helps sell the state on funding it. But meanwhile, the state's willingness to invest also helps bring in philanthropic dollars. They go together."

The project attracted donations from alumni, friends of the college, and corporations. One firm that gave generously toward construction was Newport News Shipbuilding. "We have a long and very successful relationship with Virginia Tech, which will continue with the opening of the new engineering building next fall," said Matt Mulherin (civil engineering '81), president of the shipyard. "As a Hokie, I am personally very proud to be associated with this project. As the largest industrial employer in Virginia and builder of the most-complex nuclear-powered ships in the world, we have a continuous hiring demand for engineers. This new facility will not only help produce great engineers, it will help us produce our next generation of great shipbuilders."

Knowing that the college competes at the highest echelon for engineering talent, alumni rallied to the cause, as did Steger, Benson said. "We couldn't have done it without them," Benson said, adding that Steger "has played a vital role as president. In critical moments on both sides, for donations and state support, he has come forward and put the prestige of his office, his own personal track record, behind it, and this is influential."

The Signature Engineering Building does more than serve a single college. Vice President for Administration Sherwood Wilson explained the symbolism of the entire north end's redevelopment. "In the past, when you came to campus on Prices Fork your first impression was formed by Derring Hall and a gravel parking lot. You were essentially coming in the back door where the power plant was the most iconic feature. The Signature Engineering Building and redevelopment of the north end provide a new front-door experience that reflects the university we are today. We are an internationally renowned research university, and it's important that the campus reflect that," Wilson said.

Leading the university through The Campaign for Virginia Tech: Invent the Future, which raised more than $1.1 billion, Steger has guaranteed a lasting legacy. "Having a president with Charles Steger's fundraising experience, not to mention his charisma and leadership, has made it possible to engage donors in a tremendously effective manner," said Vice President for Development and University Relations Elizabeth "Betsy" Flanagan. "Fundraising is so important in higher education, and our president's strength in this regard has made an impact not only across campus but throughout this region and the world."

Ushering Virginia Tech into the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) was a key development in Steger's presidency. There was a time, said Director of Athletics Jim Weaver, when Tech was seen as being left out in the cold. "Dr. Steger was very instrumental in getting us involved in the process," he said, particularly in collaborating with then-Gov. Mark Warner in order to earn an invitation. "That has been a very important accomplishment for us, especially the way it's unfolded the last 10 years."

Smoot said the move to the ACC is indicative of Steger's focus on big leaps: to recognize that the ACC meant a boost to athletics—and then much, much more. "It has to do with the perception of the university, the engagement with alumni and friends," Smoot said. "It provides a window, if you will, in the media to showcase the university."

On a national scale, Steger led fellow university presidents toward a decision that yielded the football playoff system. Chairing the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) Presidential Oversight Committee, Steger started one discussion by outlining the likely reactions from sports fans if the group didn't come to a consensus on a playoff. "That's Charles," said Bill Hancock, executive director of the BCS and the college football playoff, with a laugh. "He wants to be prepared.

"He has remarkable intelligence, and his wit allows him to get along with people so well," Hancock said. "We needed a consensus builder. … He was the right person at the right time for us, and the right person at the right time for college football. I suppose they might've gotten there without Dr. Steger, but I'm glad we didn't have to find out."

Steger, a cross-country runner in high school, likely relates well to the advice former president Hahn offered to the next Virginia Tech president. "The next president needs to always keep in mind that the responsibility is not a sprint; it's a long-distance race. You keep the goals constantly in mind. You may get pushed off the track here and there, but you keep focusing on the long-range goals, and that Charles has done extremely well."

On a Saturday morning in early September, however, Steger had lighter matters on his mind. Two hours before the Hokies kicked off versus Western Carolina, The Grove's front doors were wide open for a pregame reception on a gorgeous fall day, the sky painted such a perfectly clear blue so as to be unfair to other climates that claim to have good football weather. Steger and his wife circulated around the first-floor rooms and the patio, pleasantly engaged in their role as the university's hosts. Even the Stegers' dog worked the room, greeting guests and searching for dropped crumbs. A name tag identifying him as "Bo Steger" dangled off his collar, nearly reaching the ground. Naturally, he's named after a famous architect, Mario Botta.

Dressed in a tie and blazer and cloaked in a lifetime of dedication to Virginia Tech, President Steger wears his uniform well. He mirrors the university, and the university mirrors him.

"His personality and what it reflected are really the personality of the institution, and it would be really hard to separate the two," said Rose.

Produced by University Relations