The right leader at the right time

On the eve of president Torgersen's retirement, here's a look at his leadership and legacy

by Jill O. Elswick

Let's say that you've come back to Virginia Tech to attend a conference at the Donaldson Brown Hotel and Conference Center. Classes are in session; the campus is abuzz with activity. You receive your visitor's pass and drive to the parking lot across from Squires Student Center. You circle the lot for an empty parking space--no luck.

"Nothing's changed," you grumble. You park illegally by a curb. At the end of the day, a fluorescent orange ticket glares from your windshield. Furious, you shoot off an e-mail to Virginia Tech president Paul E. Torgersen. You remember his e-mail address: tennis@vt.edu. You had read somewhere that he chose this address because of his love of the sport.

You don't expect a reply. You just want to vent. And where better to complain than to the very top?

Imagine your surprise when, the next morning, you receive a personal message from Torgersen himself. The president says that since you have decided to hold him responsible for your parking ticket, he will pay the fine for you. "Wow!" you say. "He's paying my ticket!" Then--gulp. You realize that what he's really telling you is you've lost perspective on a trivial matter.

The above scenario is admittedly hypothetical. Of course you would never bother the president of a large public institution with your petty problems. But others have. And Torgersen has been known to use any diplomatic means at hand to keep shrill voices at bay--including paying a parking fine here and there--so he can get on with his real job of leading the university.

|

It's a job that, in a sense, he's held three times during his 33-year ("one-third of a century," he likes to say) career at Tech. Torgersen was interim president from William Lavery's retirement on Dec. 31, 1987, until James D. McComas took over in September 1988. In late 1993 he became interim president again, when McComas stepped down for health reasons. The board of visitors soon unanimously concluded that Torgersen was the right person to become Tech's 14th president; he was inaugurated on Jan. 1, 1994. |

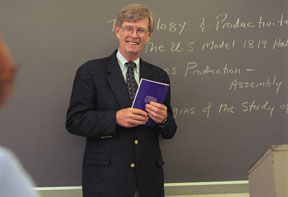

| "I consider myself a professor who is also president," says Torgersen, who has taught at least one class per semester during his entire tenure as president of Virginia Tech. |

Torgersen already held an exemplary record of leadership at Tech. As dean of the College of Engineering from 1970 to 1990, his emphasis on recruiting top-notch faculty members and attracting research dollars helped lead that college into national prominence. Many believe the college's ascendance positioned the entire university for the great leap in public esteem it enjoys today and continues to cultivate through its academic programs, research achievements, and outreach services.

One of Torgersen's first objectives as president was to identify a distinct academic focus that set Tech apart from prestigious competitors such as the University of Virginia and the College of William and Mary. Throughout the campus and across all disciplines, Torgersen saw excellence in information and instructional technology, which he vowed to coalesce into a unified thrust. "This is our horse to ride," he told his staff.

Torgersen had always championed new technology. At the very dawn of the desktop computing era in 1984, when he was dean of engineering, he required all engineering majors to own personal computers. (The university extended this requirement to all incoming students in 1998.) He served from 1982-84 on the Governor of Virginia's Task Force on Science and Technology, which led to the founding of the Virginia Center for Innovative Technology. Torgersen was Tech's first president to use e-mail and to use a laptop computer to make presentations to legislators.

Tech's information and instructional technology initiative already had a life of its own when Torgersen became president. But Torgersen amplified it. He encouraged the already established and highly praised Faculty Development Initiative to quickly infuse the use of computers throughout the curriculum. Proud that Tech was among the first "wired" campuses, Torgersen handed out newspaper and magazine clippings about the world-renowned Blacksburg Electronic Village (see www.bev.net and Virginia Tech Magazine, Winter 1998, Vol. 20, No. 2) everywhere he went.

Torgersen also actively supported the development and construction of the Math Emporium, where hundreds of Tech students now learn math at their own pace on computers. So that Tech researchers may develop wireless internet technology, Torgersen supported the purchase of a broad-bandwidth high-frequency spectrum; Tech is the only university in the nation to own such a spectrum. During his tenure, the university also developed Network Virginia, a broad-bandwidth network for Virginia that is considered a model for the next generation Internet.

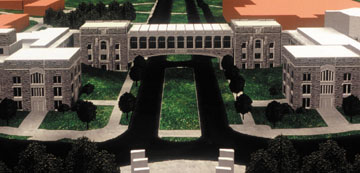

The crowning emblem of Tech's emphasis on information and instructional technology will be the Advanced Communications and Information Technology Center (ACITC), to be housed in a Hokie-stone building that, when completed next year, will arch across alumni mall to link with Newman Library. "Aesthetically what we're going to do is complete a horseshoe of Hokie-stone facilities around the Drillfield," says Torgersen. "It's an incredible location." The center will be available to all Tech students and faculty members on an interdisciplinary basis for communications and information technology research.

The boom in campus construction during Torgersen's presidency has seen the following buildings completed: the Northern Virginia Center in Alexandria; a new engineering building; the architecture program's underground facility, Burchard Hall; the athletic program's Merryman Center; McComas Hall for student exercise and recreation; the Johnson Miller Track Complex; the Fralin Biotechnology Center; and three new dormitories. Also during Torgersen's tenure the Hotel Roanoke reopened, completing an initiative begun in the McComas era.

But Hokie stone and mortar don't go up by magic; it takes money, and lots of it. From day one, Torgersen assumed the role of breadwinner for the university. He traveled throughout Virginia to build relationships with senators and delegates of the General Assembly. Weakened by years of budget cuts, Tech urgently needed resources. Faculty salaries at Tech, for example, had fallen within a margin of 30 percent less than those at peer universities.

Torgersen set out to bring Tech's resources up to snuff, not only by making a case with the legislature, but also through spearheading the university's $225 million capital campaign--a campaign so successful it far surpassed its goal, for a total of $337 million. "There's a margin between being a halfway decent institution and a truly distinguished institution, and that margin is largely determined by private funds--professorships, chairs, scholarship monies--that permit you to attract better students and keep good faculty members," says Torgersen.

Funds for the ACITC came in part from the Virginia legislature and from the U.S. Congress but fell short by more than half of the $27 million needed to construct the building. Torgersen's campaign to raise private funds for the building met with astonishing success; one anonymous donor gave $5 million. Upon realizing that the building was $2 million over budget, Torgersen pleaded with the General Assembly to provide the final sum--and got it.

One of Torgersen's strongest arguments for legislative funding has been Tech's impact on economic growth in Virginia. In a 1994 speech to the Economic Developers Association, Torgersen stressed the land-grant university's mandate to bring "real-world solutions to real-world problems" to the "farms, homes, and workplaces of ordinary citizens." At that time, Tech was fulfilling its mandate through incentives for faculty members to commercialize research and through research partnerships with businesses. The not-for-profit corporation Virginia Tech Intellectual Properties was marketing the university's intellectual properties; and the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center (CRC), which Torgersen headed as president from 1990 to the time of his inauguration, had become an incubator for fledgling businesses begun by Tech faculty members.

Torgersen elevated the university's role in economic development by creating a full-time senior position to coordinate Tech's economic initiatives. That office is the university's "front door for businesses," says Torgersen, who adds that as a result the university is much more coherent in its response to business inquiries.

Yet Torgersen was more likely to downsize than to create new positions at the university. He explains his decision to run a small staff: "I think the president's office has to set an example for using resources wisely. You can't go out into the colleges and say, 'We really can't afford this new chemistry lab,' when they see a lot of fat in the operation of your office." He believes that a small, well-chosen staff can achieve more because no one gets in anyone else's way.

Like all leaders worth their salt, Torgersen is known for making shrewd staff appointments. He hires the right people, he says, then leaves them alone to do their jobs. But if he feels that someone is not pulling the proper amount of weight for the university or has developed a self-serving focus, he takes action. His tactics have ranged from one-time reprimands to "or else" demands that the person live up to his or her job description.

By and large, however, Torgersen's relationship with his co-workers has been one of mutual admiration. A great sender of thank-you notes, he never fails to give credit where it's due, says Carole Nickerson, Torgersen's hand-picked executive assistant. With his informal management style, he is eminently approachable. He takes pains to get his paperwork done before business hours and on weekends so he can leave his door open in case staff members--or others--want an ear with the president. He solicits everyone's ideas, believing that a collaborative approach leads to a richer result.

Torgersen listens to everyone--almost. "He has a harder time with people who are grim and hopeless about things," says Nickerson. A problem-solver and an optimist, Torgersen is often heard to say, "We're gaining!" or "This is going to work out." He doesn't dwell on the past; he has little time for post-mortems.

But while Torgersen may be impatient with pessimists, he has a great deal of compassion for people who are simply having a hard time. "He keeps track of who's in deep water or is experiencing a personal tragedy," says Nickerson. Torgersen often makes rounds in Burruss Hall and throughout the campus to encourage people. "He does more of what my friends in the Jewish faith call 'mitzvahs' than people would imagine," says Nickerson, who defines 'mitzvah' as a kindness or small blessing.

While it has not been highly publicized, Torgersen has also performed small blessings for several of his students, buying textbooks, for example, for the cash-strapped. When one of his students learned that his father was dying, Torgersen bought the student an airline ticket to go visit his father. On a smaller but still significant level, Torgersen regularly purchases miniature chocolate bars to keep the crystal bowl in his office brimming with sweets for visitors. "It's his way of humanizing the space," says Nickerson.

The chocolates, it seems, are more important for Torgersen to have in his office than new furniture or upscale carpeting. He has refused to have the stained wallpaper behind his executive desk replaced. He agreed to purchase new chairs when the stuffing started coming out of the old ones--but used private dollars to fund them. On his trips to meet legislators, he drives a modest Chevy Cavalier from the motor pool. He avoids luxury hotels and insists on the government rate for lodging whenever it is available. Torgersen strongly believes that a president's duty is to uphold the values of the organization--in this case, the wise use of resources.

A good leader, says Torgersen, is also an opportunist. Someone who by design takes advantage of chance; someone who can "go with the flow" and still accomplish the organization's objectives. "I'm a great believer in planning," he says, "but only up to a point. You have to seize the moment. In part it falls together and in part you orchestrate it."

| Examples abound of Torgersen's ability to make difficult decisions at opportune times. When the deanships in the College of Education and the College of Human Resources were both vacant by coincidence, Torgersen seized the chance to merge the two colleges, which not only saved money, but "was a natural merging of disciplines," he says. |  |

| Torgersen lobbied hard for the $27 million needed to construct the Advanced Communications and Information Technology Center, which will be open to all Tech students and faculty members on an interdisciplinary basis for communication and information technology research. |

When Tech was plagued by an e-mail insulting to African-Americans, and ensuing weeks revealed profound social rifts in the campus community, Torgersen established a new senior level position, vice president of multicultural affairs. Following a national search, Benjamin Dixon took office over a year ago.

Faced with a number of embarrassing Tech football player arrests in 1996, Torgersen appointed athletic director Dave Braine to chair a committee to devise checks on athlete misbehavior; the resulting Comprehensive Action Plan has become a model for other colleges and universities. Braine, now athletic director at Georgia Tech, recalls, "He directed me to put together an action plan and said he expected the problems to stop, simple as that. And they did." Torgersen's disciplinary action was deemed an act of "tough love" because of his well-known pride in Tech's athletic program, which rose to national prominence during his watch--football coach Frank Beamer led the Hokies to a bowl game every year of Torgersen's tenure.

But academics, not sports, comes first with Torgersen. He refused to match Georgia Tech's salary offer to the hugely popular Braine because it would have sent the wrong message to pay an athletic administrator substantially more than the highest ranking academic, the provost.

Torgersen, moreover, has always seen himself as a teacher first: "I consider myself a professor who is also president," he says. The John W. Hancock Jr. Chair in Engineering, Torgersen enjoys--and values--teaching so much that, even as president, he has taught at least one class per semester since he joined the engineering faculty in 1967. In 1984 undergraduate engineering students raised $20,000 to endow a scholarship in his name. In 1992 he received the student nominated Sporn Award in recognition of teaching excellence.

While president, Torgersen enacted the University Pledge, which promises that 90 percent of Tech's courses will be taught by professors, not graduate students. Among the other academic accomplishments of the Torgersen years: the intelligent-vehicle test bed dubbed the "Smart Road" began construction, the School of the Arts was established, and the School of Public and International Affairs was established.

Torgersen has made an indelible mark on Virginia Tech, and there's an uncanny sense that he was exactly the right leader at the right time for the university. Through it all, Torgersen graced the role with a disarming sense of humor. In the reception area of the president's office stands a photo of his grandchildren's dog; the dog sits sweetly on Torgersen's executive chair. "See how hard it is to be president?" Torgersen would joke with his staff, implying that even a dog could do it.

But if leading the university looked easy for Torgersen, it was only in the same way that it looks "easy" for a Wimbledon champion to serve an ace. Torgersen's successor will be blessed to find Virginia Tech at the height of its game and ready for new victories.

Home | News | Features | Philanthropy | Athletics | Alumni | Classnotes | Editor's Page