by Mason Adams and Jesse Tuel

Photos by Logan Wallace

"They did nothing to deserve this."

"They did nothing to deserve this."

— Siddhartha Roy, Virginia Tech civil engineering

doctoral student

In January, Lee-Anne Walters picked up two bottles of filthy, yellow water and turned to her twins, Gavin and Garrett, in a Durham Hall laboratory on Virginia Tech's campus.

"Let's see if you guys remember this," she said, holding up the bottles. "Do you remember what this is? What is that?"

That's the yucky water," Gavin replied.

The boys understood. And their mother understood all too well.

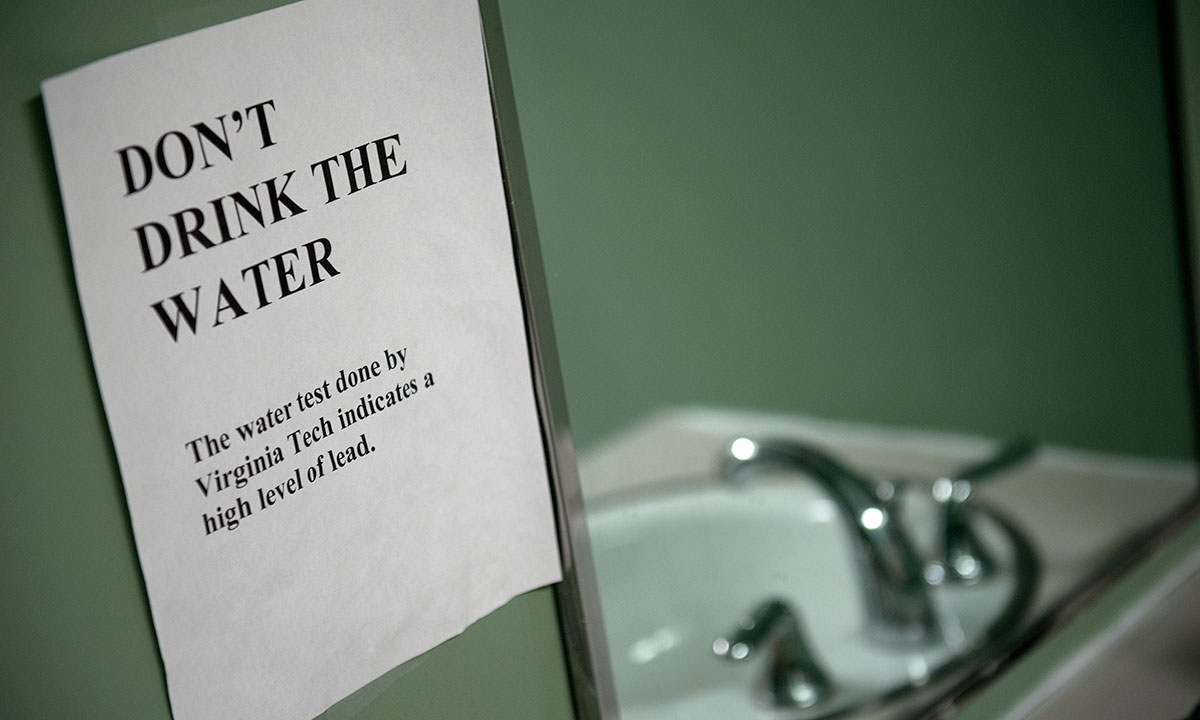

In late 2014 at her home in Flint, Michigan, Walters was at a breaking point. The tap water was giving the twins persistent rashes. Her eyelashes had begun to fall out, as had her older daughter's hair, and her older son suffered from abdominal pain. City testing found high levels of lead in her home's water, but she couldn't get further help from city and Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) officials.

An Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) official referred Walters to a scientist whose reputation for protecting the public preceded him: Marc Edwards, the Charles Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Virginia Tech.

By then, Walters, out of necessity, was fast becoming a citizen-scientist and advocate for Flint residents. In an April 2015 phone call, Edwards taught Walters how to properly collect water samples from her faucets.

Of the 30 samples Edwards tested in his lab at Virginia Tech, the lowest lead level was 300 parts per billion (ppb). The average was 2,000 ppb, and the highest was more than 13,000 ppb.

The level regarded as actionable by the EPA? 15 ppb.

The level regarded as safe? Zero ppb.

"That was a sleepless night," Edwards said. "We got [the testing] done within 24 hours. We didn't believe it. We ran the samples again the next day. Unfortunately, the results were correct. It was the worst lead in water I'd seen in 25-plus years, and I'd seen a lot."

The world now knows what happened next: Edwards and a team of student researchers determined that Flint faced widespread elevated levels of lead and dangerous Legionella bacteria; united a coalition of Flint residents and others; and helped to expose a citywide health crisis that should serve as a warning for all communities facing crumbling infrastructure.

"The most powerful force in the universe"

Gavin Walters, with his mother Lee-Anne, holds a bottle of water taken from his home in Flint, Michigan—water that gave him lead poisoning.

In late January, Walters and her family traveled to Blacksburg, where she received a heroism award during a presentation by Tech's Flint Water Study research team. In opening remarks, Provost Thanassis Rikakis called the work a stellar example of a contemporary land-grant university solving problems in a real-world context, with Flint as the classroom.

More than 500 people filled the Quillen Family Auditorium and two overflow rooms at Goodwin Hall, and 1,900 others watched a livestream broadcast to hear from the Hokies who had merged their academic skills with the spirit of Ut Prosim (That I May Serve) to champion and safeguard the health of Flint residents—affectionately known as "Flintstones"—and expose governmental malpractice.

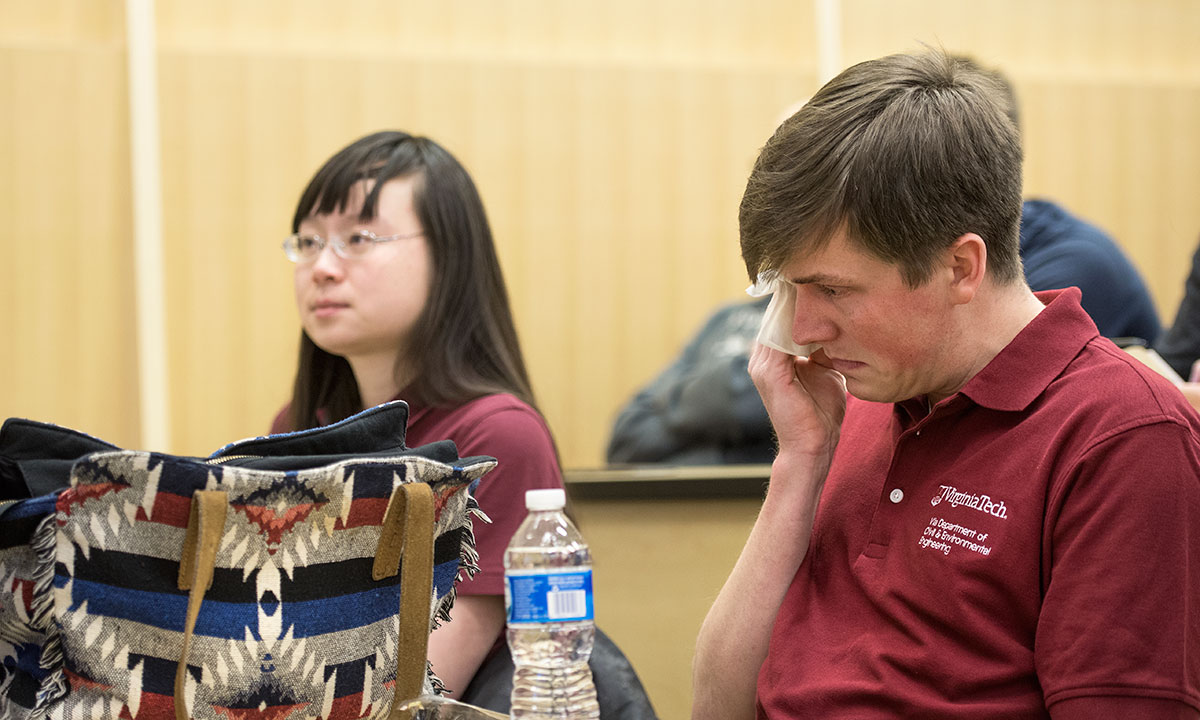

That evening, student researchers described how they had detected high lead levels, the presence of dangerous microbes, and the lack of proper corrosion control in Flint water. Some fought back tears as they described their interactions with both frightened residents and skeptical bureaucrats who had openly questioned the Tech team's methods and reputation and denied the existence of a problem even after the team had announced its results.

"For 18 months, 100,000 residents were exposed to toxic water," said Siddhartha Roy, a civil engineering Ph.D. student. "They did nothing to deserve this. Nine thousand kids were potentially exposed."

Lead poisoning causes irreversible damage: learning disabilities and mental impairment, along with a variety of physical symptoms, including abdominal pains, fatigue, headaches, loss of developmental skills, and more. In Flint, the poisoning was widespread: In some zip codes in summer 2015, 1 in 10 children had elevated blood lead levels.

Speaking in the Quillen auditorium, Roy described a call he had received from a woman who was in tears because she had given her children and grandchildren tap water. "She told me she poisoned her kids," Roy said. "It wasn't her fault. But a mother's heart could never accept that. She thanked all of us for what we did. This is why we spent the last six months of our life pulling all-nighters, pulling weekends together, because we cared. And it changed who we are as human beings."

Edwards, the driving force behind the Virginia Tech effort, turned the credit back toward Flint residents—specifically Lee-Anne Walters.

"I tell my students if they learn one thing from their class, it's that the most powerful force in the universe is a mother worried about the health of her child," Edwards told the crowd. "If you threaten that, Mama will come and mess you up, even if you're a powerful government agency."

Corrosive lessons

Like many of the industrial cities in the Rust Belt, Flint has struggled, its population falling from about 200,000 in 1960 to 100,000 today, with about 40 percent of its residents living below the poverty line. These economic pressures point to a unique trait in Michigan governance—emergency managers—that played a role in the water crisis.

When a school district, city, town, or county is in severe financial stress, the state can appoint an emergency manager with power to overrule local elected officials, said Curt Guyette, a reporter for the Michigan American Civil Liberties Union, who has written extensively about the situation in Flint. During the Flint crisis, the emergency manager position changed hands, introducing even more volatility to an already difficult dynamic.

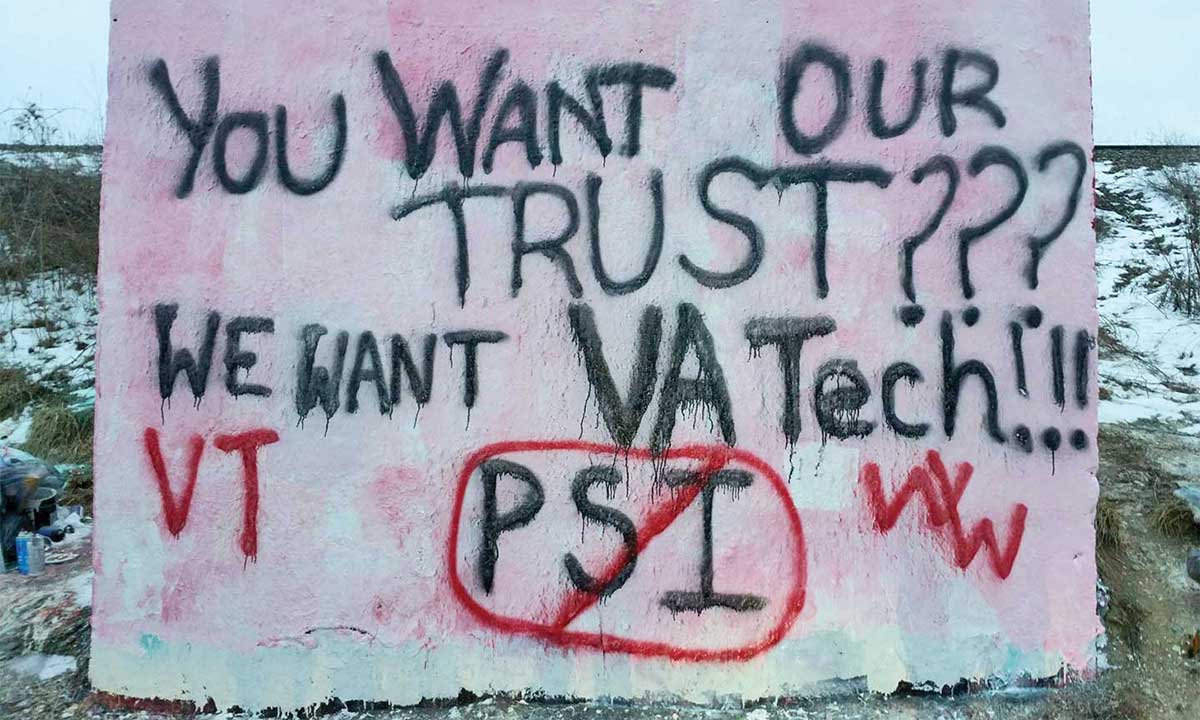

In March 2013, the Flint City Council opted to stop buying water from Detroit and to join a regional water authority that would draw water from Lake Huron and send it to Flint by pipeline. While the pipeline was under construction, a process that continues today, the emergency manager decided that Flint should use the Flint River as its water source. As soon as the switch was made in April 2014, residents began complaining about the smell, taste, and color of their new water. Protesters soon packed city hall with bottles of discolored, cloudy water.

In a June 2015 memo, Miguel Del Toral, the regulations manager in the EPA's groundwater and drinking water branch, who referred Walters to Edwards, released a memo based on Edwards' testing of Walters' 30 samples, outlining the astronomical levels of lead, the timeline of events, and the laws (i.e., corrosion control) the city wasn't following. An EPA official above Del Toral tried to bury the memo, and state officials downplayed the results.

Edwards, unfortunately, recognized what could be happening. More than a decade ago, the Washington, D.C., water utility had invalidated samples that pointed to rising lead levels and had issued a report claiming the water met federal standards, while the Centers for Disease Control claimed the water was safe and that no D.C. residents had been harmed. Edwards, dubbed "The Plumbing Professor" by Time magazine in 2004, spent years fighting the agencies—with his own money and reputation on the line—in order to protect D.C. residents.

In other cities, too—Durham and Greenville, North Carolina; New Orleans; and more—Edwards has uncovered lead in the water and fought for the public. "It's the same movie," Edwards said. "It's the same ending. It's the fifth time I've seen it, so it's a little sad."

Learning from experience

The lessons of D.C. formed the core of a graduate-level course, Engineering Ethics and the Public, taught each fall in Blacksburg by Edwards and Yanna Lambrinidou, an adjunct assistant professor in the Department of Science and Technology Studies in Tech's National Capital Region, who collaborated with Edwards on the D.C. crisis.

Taught since 2010, the course has had a powerful influence on the Flint team's students, and Flint has influenced the course: The crisis served as a case study in the fall 2015 semester. Of primary importance in the curriculum is the first, fundamental canon in the National Society of Professional Engineers' code of ethics: to hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public. In recent years, however, and perhaps with increasing frequency, Edwards said, scientists and engineers avoid engagement by claiming that they only play an objective, numbers-based role.

"There's a role that scientists and engineers need to play and that society expects them to play, which is to act and react when they see wrongdoing," Lambrinidou said. "Through inaction, you're enabling the biggest or most powerful and oftentimes the most dangerous and harmful fish in the pool to win. You're taking an active part in reinforcing existing infrastructures and existing imbalances and injustice by staying silent."

Lambrinidou said that in both Washington, D.C., and Flint, residents and citizen-activists were the first to sound alarms about problems with the water. "It was ordinary people, non-experts, parents who discovered their children had elevated blood lead levels and called begging to have their service lines replaced," Lambrinidou said. "We end up as a society and culture [creating] these narratives where we almost invariably place expert knowledge above the knowledge of ordinary people. Ignoring those [ordinary] voices is very, very risky."

By listening to and collaborating with local experts and mobilizing to address the complex problem on-site, the Tech research team perfectly embodies the powerful model for problem-solving that few institutions, apart from the contemporary land-grant university, have offered. In fact, water as an area of excellence is an emerging priority for Virginia Tech.

In a May 2015 speech on academic freedom that Edwards delivered just before analyzing Walters' water samples, the professor quoted Abraham Lincoln, who established the land-grant university system by signing the Morrill Act: The "system is being built on behalf of the people, who have invested in these public universities their hopes, their support, and their confidence." Added Edwards, "The 21st century will surely provide us with many opportunities to prove ourselves worthy of the people, their hope, and confidence… but only if we can find the courage and strength to act on our convictions."

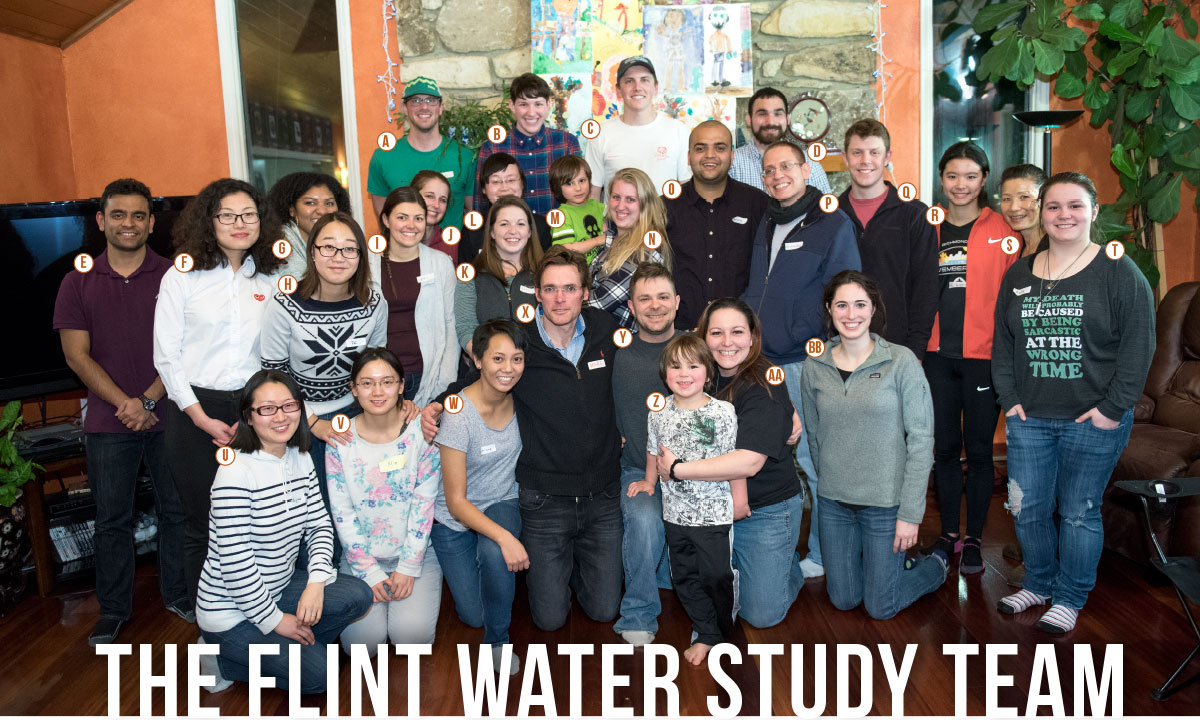

In late January, the Walters family gathered with some of Tech's Flint Water Study team for a potluck dinner at Professor Edwards' home. When the team mobilized—going "all in for Flint," as Edwards said—the students found themselves fighting alongside citizen-activists for the safety of the city's residents.

• NAMES

A. Owen Strom: 25, 32, 34, 36

B. Maggie Carolan: 10, 24, 33, 36, 46

C. William Rhoads: 5, 8, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39

D. Robert Bielitz: 14

E. Siddhartha Roy: 7, 8, 20, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 38, 43

F. Ni "Joyce" Zhu: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 44

G. Taylor Bradley: 26

H. Fei Wang: 6, 32, 34

I. Victoria Nystrom: 9, 22, 32, 34, 38

J. Laurel Strom: 9, 32, 34, 36, 38

K. Emily Garner: 8, 32, 36, 38, 39

L. Pan Ji: 8, 32, 36, 38

M. Gavin Walters: 50

N. Christina Devine: 8, 15, 32, 37

O. Anurag Mantha: 8, 32, 35, 38, 40, 45, 46

P. David "Otto" Schwake: 6, 36, 42, 44, 46

Q. Donnie Martin: 49

R. Ailene Edwards: 48

S. Jui-ling Edwards: 47

T. Kaylie Mosteller: 50

U. Dongjuan Dai: 6, 28

V. Min Tang: 8, 21, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44

W. Kristine Mapili: 11, 34

X. Marc Edwards: 1, 42, 43, 45

Y. Dennis Walters: 50

Z. Garrett Walters: 50

AA. Lee-Anne Walters: 51

BB. Rebekah Martin: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42

• NOT PICTURED

Amy Pruden: 2, 4

Joseph Falkinham III: 3, 4

Brandi Clark: 5, 6, 16

Sheldon Masters: 6, 17, 28

Jeffrey Parks: 6, 18, 29, 30, 32, 35

Kelsey Pieper: 6, 19, 32

Jake Metch: 8, 32, 36

Colin Richards: 9, 32, 34, 42

Catherine Grey: 9, 23, 33, 35, 46

Kim Hughes: 13, 32, 34, 36

Rebecca Jones: 12, 32, 34

Alison Vick: 11, 32, 34

Maddie Brouse: 11, 33, 35, 36, 46

Matthew Dowdle: 11, 33, 35, 46

Sara Chergaoui: 11, 27, 33, 35, 46

• ROLES

1 Team's faculty leader; Charles P. Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, College of Engineering; and principal investigator, National Science Foundation (NSF) Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grant

2 College of Engineering professor and Graduate School associate dean and director of interdisciplinary graduate education

3 Professor of biological sciences, College of Science

4 Co-principal investigator, NSF RAPID grant

5 Helped with NSF grant proposal

6 Research scientist

7 Team's student leader. Launched flintwaterstudy.org; raised about $100,000 to support the team in Flint and for future work; and prepared a mini-documentary on the team's response, designed to attract young students to environmental engineering

8 Ph.D. student, civil engineering

9 Master's degree student, civil engineering

10 Undergraduate double major in geography and water: resources, policy, and management

11 Undergraduate, civil engineering

12 Undergraduate, environmental science

13 Biochemistry, biology '15

14 Undergraduate, general engineering

15 Engineering science and mechanics '14

16 M.S. environmental engineering '12, Ph.D. civil engineering '15

17 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. '15

18 M.S. environmental engineering '01, Ph.D. civil engineering '05

19 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. biological systems engineering '15

20 M.S. environmental engineering '15

21 M.S. environmental engineering '13

22 Biological systems engineering '15

23 Civil engineering '15

24 Research assistant

25 Master's degree student, public health, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

26 Civil engineering graduate student at Howard University, joining Edwards' team in fall 2016 and pursuing a master's in environmental engineering

27 Exchange student

28 Helped plan response to crisis

29 Prepared sampling video for residents

30 Oversaw assembly, distribution, return, and pre-analysis prep of lead test kits and coordinated various sampling efforts

31 Conducted sampling in Flint

32 Assembled, processed, and analyzed lead testing kits

33 Distributed and collected lead test kits

34 Prepped test kits for analysis

35 Communicated with residents about testing

36 Assembled, processed, and analyzed microbial testing kits

37 Compared the corrosiveness of Flint water to Detroit's and, via webcam, demonstrated the tests for Flint elementary school students who replicated the experiments

38 Freedom of Information Act requests and analyses

39 Tuition remission in support of studies

40 Handled logistics, managed data, raised money to distribute filters, oversaw social media outreach and correspondence

41 Compared Virginia Tech data to Michigan Department of Environmental Quality data

42 First trip to Flint

43 Second trip to Flint

44 Third trip to Flint

45 Fourth trip to Flint

46 Fifth trip to Flint (spring break)

47 Marc Edwards' wife

48 Marc Edwards' daughter

49 Rebekah Martin's husband

50 Lee-Anne Walters' family

51 Citizen-scientist

• NAMES

A. Owen Strom: 25, 32, 34, 36

B. Maggie Carolan: 10, 24, 33, 36, 46

C. William Rhoads: 5, 8, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39

D. Robert Bielitz: 14

E. Siddhartha Roy: 7, 8, 20, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 38, 43

F. Ni "Joyce" Zhu: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 44

G. Taylor Bradley: 26

H. Fei Wang: 6, 32, 34

I. Victoria Nystrom: 9, 22, 32, 34, 38

J. Laurel Strom: 9, 32, 34, 36, 38

K. Emily Garner: 8, 32, 36, 38, 39

L. Pan Ji: 8, 32, 36, 38

M. Gavin Walters: 50

N. Christina Devine: 8, 15, 32, 37

O. Anurag Mantha: 8, 32, 35, 38, 40, 45, 46

P. David "Otto" Schwake: 6, 36, 42, 44, 46

Q. Donnie Martin: 49

R. Ailene Edwards: 48

S. Jui-ling Edwards: 47

T. Kaylie Mosteller: 50

U. Dongjuan Dai: 6, 28

V. Min Tang: 8, 21, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44

W. Kristine Mapili: 11, 34

X. Marc Edwards: 1, 42, 43, 45

Y. Dennis Walters: 50

Z. Garrett Walters: 50

AA. Lee-Anne Walters: 51

BB. Rebekah Martin: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42

• NOT PICTURED

Amy Pruden: 2, 4

Joseph Falkinham III: 3, 4

Brandi Clark: 5, 6, 16

Sheldon Masters: 6, 17, 28

Jeffrey Parks: 6, 18, 29, 30, 32, 35

Kelsey Pieper: 6, 19, 32

Jake Metch: 8, 32, 36

Colin Richards: 9, 32, 34, 42

Catherine Grey: 9, 23, 33, 35, 46

Kim Hughes: 13, 32, 34, 36

Rebecca Jones: 12, 32, 34

Alison Vick: 11, 32, 34

Maddie Brouse: 11, 33, 35, 36, 46

Matthew Dowdle: 11, 33, 35, 46

Sara Chergaoui: 11, 27, 33, 35, 46

• ROLES

1 Team's faculty leader; Charles P. Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, College of Engineering; and principal investigator, National Science Foundation (NSF) Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grant

2 College of Engineering professor and Graduate School associate dean and director of interdisciplinary graduate education

3 Professor of biological sciences, College of Science

4 Co-principal investigator, NSF RAPID grant

5 Helped with NSF grant proposal

6 Research scientist

7 Team's student leader. Launched flintwaterstudy.org; raised about $100,000 to support the team in Flint and for future work; and prepared a mini-documentary on the team's response, designed to attract young students to environmental engineering

8 Ph.D. student, civil engineering

9 Master's degree student, civil engineering

10 Undergraduate double major in geography and water: resources, policy, and management

11 Undergraduate, civil engineering

12 Undergraduate, environmental science

13 Biochemistry, biology '15

14 Undergraduate, general engineering

15 Engineering science and mechanics '14

16 M.S. environmental engineering '12, Ph.D. civil engineering '15

17 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. '15

18 M.S. environmental engineering '01, Ph.D. civil engineering '05

19 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. biological systems engineering '15

20 M.S. environmental engineering '15

21 M.S. environmental engineering '13

22 Biological systems engineering '15

23 Civil engineering '15

24 Research assistant

25 Master's degree student, public health, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

26 Civil engineering graduate student at Howard University, joining Edwards' team in fall 2016 and pursuing a master's in environmental engineering

27 Exchange student

28 Helped plan response to crisis

29 Prepared sampling video for residents

30 Oversaw assembly, distribution, return, and pre-analysis prep of lead test kits and coordinated various sampling efforts

31 Conducted sampling in Flint

32 Assembled, processed, and analyzed lead testing kits

33 Distributed and collected lead test kits

34 Prepped test kits for analysis

35 Communicated with residents about testing

36 Assembled, processed, and analyzed microbial testing kits

37 Compared the corrosiveness of Flint water to Detroit's and, via webcam, demonstrated the tests for Flint elementary school students who replicated the experiments

38 Freedom of Information Act requests and analyses

39 Tuition remission in support of studies

40 Handled logistics, managed data, raised money to distribute filters, oversaw social media outreach and correspondence

41 Compared Virginia Tech data to Michigan Department of Environmental Quality data

42 First trip to Flint

43 Second trip to Flint

44 Third trip to Flint

45 Fourth trip to Flint

46 Fifth trip to Flint (spring break)

47 Marc Edwards' wife

48 Marc Edwards' daughter

49 Rebekah Martin's husband

50 Lee-Anne Walters' family

51 Citizen-scientist

• NAMES

A. Owen Strom: 25, 32, 34, 36

B. Maggie Carolan: 10, 24, 33, 36, 46

C. William Rhoads: 5, 8, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39

D. Robert Bielitz: 14

E. Siddhartha Roy: 7, 8, 20, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 38, 43

F. Ni "Joyce" Zhu: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 44

G. Taylor Bradley: 26

H. Fei Wang: 6, 32, 34

I. Victoria Nystrom: 9, 22, 32, 34, 38

J. Laurel Strom: 9, 32, 34, 36, 38

K. Emily Garner: 8, 32, 36, 38, 39

L. Pan Ji: 8, 32, 36, 38

M. Gavin Walters: 50

N. Christina Devine: 8, 15, 32, 37

O. Anurag Mantha: 8, 32, 35, 38, 40, 45, 46

P. David "Otto" Schwake: 6, 36, 42, 44, 46

Q. Donnie Martin: 49

R. Ailene Edwards: 48

S. Jui-ling Edwards: 47

T. Kaylie Mosteller: 50

U. Dongjuan Dai: 6, 28

V. Min Tang: 8, 21, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44

W. Kristine Mapili: 11, 34

X. Marc Edwards: 1, 42, 43, 45

Y. Dennis Walters: 50

Z. Garrett Walters: 50

AA. Lee-Anne Walters: 51

BB. Rebekah Martin: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42

• NOT PICTURED

Amy Pruden: 2, 4

Joseph Falkinham III: 3, 4

Brandi Clark: 5, 6, 16

Sheldon Masters: 6, 17, 28

Jeffrey Parks: 6, 18, 29, 30, 32, 35

Kelsey Pieper: 6, 19, 32

Jake Metch: 8, 32, 36

Colin Richards: 9, 32, 34, 42

Catherine Grey: 9, 23, 33, 35, 46

Kim Hughes: 13, 32, 34, 36

Rebecca Jones: 12, 32, 34

Alison Vick: 11, 32, 34

Maddie Brouse: 11, 33, 35, 36, 46

Matthew Dowdle: 11, 33, 35, 46

Sara Chergaoui: 11, 27, 33, 35, 46

• ROLES

1 Team's faculty leader; Charles P. Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, College of Engineering; and principal investigator, National Science Foundation (NSF) Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grant

2 College of Engineering professor and Graduate School associate dean and director of interdisciplinary graduate education

3 Professor of biological sciences, College of Science

4 Co-principal investigator, NSF RAPID grant

5 Helped with NSF grant proposal

6 Research scientist

7 Team's student leader. Launched flintwaterstudy.org; raised about $100,000 to support the team in Flint and for future work; and prepared a mini-documentary on the team's response, designed to attract young students to environmental engineering

8 Ph.D. student, civil engineering

9 Master's degree student, civil engineering

10 Undergraduate double major in geography and water: resources, policy, and management

11 Undergraduate, civil engineering

12 Undergraduate, environmental science

13 Biochemistry, biology '15

14 Undergraduate, general engineering

15 Engineering science and mechanics '14

16 M.S. environmental engineering '12, Ph.D. civil engineering '15

17 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. '15

18 M.S. environmental engineering '01, Ph.D. civil engineering '05

19 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. biological systems engineering '15

20 M.S. environmental engineering '15

21 M.S. environmental engineering '13

22 Biological systems engineering '15

23 Civil engineering '15

24 Research assistant

25 Master's degree student, public health, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

26 Civil engineering graduate student at Howard University, joining Edwards' team in fall 2016 and pursuing a master's in environmental engineering

27 Exchange student

28 Helped plan response to crisis

29 Prepared sampling video for residents

30 Oversaw assembly, distribution, return, and pre-analysis prep of lead test kits and coordinated various sampling efforts

31 Conducted sampling in Flint

32 Assembled, processed, and analyzed lead testing kits

33 Distributed and collected lead test kits

34 Prepped test kits for analysis

35 Communicated with residents about testing

36 Assembled, processed, and analyzed microbial testing kits

37 Compared the corrosiveness of Flint water to Detroit's and, via webcam, demonstrated the tests for Flint elementary school students who replicated the experiments

38 Freedom of Information Act requests and analyses

39 Tuition remission in support of studies

40 Handled logistics, managed data, raised money to distribute filters, oversaw social media outreach and correspondence

41 Compared Virginia Tech data to Michigan Department of Environmental Quality data

42 First trip to Flint

43 Second trip to Flint

44 Third trip to Flint

45 Fourth trip to Flint

46 Fifth trip to Flint (spring break)

47 Marc Edwards' wife

48 Marc Edwards' daughter

49 Rebekah Martin's husband

50 Lee-Anne Walters' family

51 Citizen-scientist

• NAMES

A. Owen Strom: 25, 32, 34, 36

B. Maggie Carolan: 10, 24, 33, 36, 46

C. William Rhoads: 5, 8, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39

D. Robert Bielitz: 14

E. Siddhartha Roy: 7, 8, 20, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 38, 43

F. Ni "Joyce" Zhu: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 44

G. Taylor Bradley: 26

H. Fei Wang: 6, 32, 34

I. Victoria Nystrom: 9, 22, 32, 34, 38

J. Laurel Strom: 9, 32, 34, 36, 38

K. Emily Garner: 8, 32, 36, 38, 39

L. Pan Ji: 8, 32, 36, 38

M. Gavin Walters: 50

N. Christina Devine: 8, 15, 32, 37

O. Anurag Mantha: 8, 32, 35, 38, 40, 45, 46

P. David "Otto" Schwake: 6, 36, 42, 44, 46

Q. Donnie Martin: 49

R. Ailene Edwards: 48

S. Jui-ling Edwards: 47

T. Kaylie Mosteller: 50

U. Dongjuan Dai: 6, 28

V. Min Tang: 8, 21, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44

W. Kristine Mapili: 11, 34

X. Marc Edwards: 1, 42, 43, 45

Y. Dennis Walters: 50

Z. Garrett Walters: 50

AA. Lee-Anne Walters: 51

BB. Rebekah Martin: 8, 31, 32, 36, 38, 41, 42

• NOT PICTURED

Amy Pruden: 2, 4

Joseph Falkinham III: 3, 4

Brandi Clark: 5, 6, 16

Sheldon Masters: 6, 17, 28

Jeffrey Parks: 6, 18, 29, 30, 32, 35

Kelsey Pieper: 6, 19, 32

Jake Metch: 8, 32, 36

Colin Richards: 9, 32, 34, 42

Catherine Grey: 9, 23, 33, 35, 46

Kim Hughes: 13, 32, 34, 36

Rebecca Jones: 12, 32, 34

Alison Vick: 11, 32, 34

Maddie Brouse: 11, 33, 35, 36, 46

Matthew Dowdle: 11, 33, 35, 46

Sara Chergaoui: 11, 27, 33, 35, 46

• ROLES

1 Team's faculty leader; Charles P. Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, College of Engineering; and principal investigator, National Science Foundation (NSF) Rapid Response Research (RAPID) grant

2 College of Engineering professor and Graduate School associate dean and director of interdisciplinary graduate education

3 Professor of biological sciences, College of Science

4 Co-principal investigator, NSF RAPID grant

5 Helped with NSF grant proposal

6 Research scientist

7 Team's student leader. Launched flintwaterstudy.org; raised about $100,000 to support the team in Flint and for future work; and prepared a mini-documentary on the team's response, designed to attract young students to environmental engineering

8 Ph.D. student, civil engineering

9 Master's degree student, civil engineering

10 Undergraduate double major in geography and water: resources, policy, and management

11 Undergraduate, civil engineering

12 Undergraduate, environmental science

13 Biochemistry, biology '15

14 Undergraduate, general engineering

15 Engineering science and mechanics '14

16 M.S. environmental engineering '12, Ph.D. civil engineering '15

17 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. '15

18 M.S. environmental engineering '01, Ph.D. civil engineering '05

19 M.S. civil engineering '11, Ph.D. biological systems engineering '15

20 M.S. environmental engineering '15

21 M.S. environmental engineering '13

22 Biological systems engineering '15

23 Civil engineering '15

24 Research assistant

25 Master's degree student, public health, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

26 Civil engineering graduate student at Howard University, joining Edwards' team in fall 2016 and pursuing a master's in environmental engineering

27 Exchange student

28 Helped plan response to crisis

29 Prepared sampling video for residents

30 Oversaw assembly, distribution, return, and pre-analysis prep of lead test kits and coordinated various sampling efforts

31 Conducted sampling in Flint

32 Assembled, processed, and analyzed lead testing kits

33 Distributed and collected lead test kits

34 Prepped test kits for analysis

35 Communicated with residents about testing

36 Assembled, processed, and analyzed microbial testing kits

37 Compared the corrosiveness of Flint water to Detroit's and, via webcam, demonstrated the tests for Flint elementary school students who replicated the experiments

38 Freedom of Information Act requests and analyses

39 Tuition remission in support of studies

40 Handled logistics, managed data, raised money to distribute filters, oversaw social media outreach and correspondence

41 Compared Virginia Tech data to Michigan Department of Environmental Quality data

42 First trip to Flint

43 Second trip to Flint

44 Third trip to Flint

45 Fourth trip to Flint

46 Fifth trip to Flint (spring break)

47 Marc Edwards' wife

48 Marc Edwards' daughter

49 Rebekah Martin's husband

50 Lee-Anne Walters' family

51 Citizen-scientist

Born heroes

In September and October 2015, Virginia Tech team members poured themselves into the Flint effort, pushing forward on multiple fronts. One game-changer, they said, was when Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Flint's Hurley Medical Center, announced her findings. With access to citywide blood testing data and the Virginia Tech testing results posted online, Hanna-Attisha identified an increased incidence of elevated lead levels in infants and children. And the children whose blood displayed the worst increases in lead lived in neighborhoods that matched the areas where the highest levels of lead had been detected by Tech's August sampling of 300 sites.

A first for water

Margaret "Maggie" Carolan (above) is one of the first students to pursue Tech's new bachelor's degree in water—water: resources, policy, and management—a cross-disciplinary major that incorporates water science, policy, law, economics, management, and social science. Twenty-one students already have enrolled in the major, first offered in fall 2015.

Carolan, a sophomore who is also majoring in geography, has received the Alumni Presidential Scholarship, along with two scholarships established by Jeff Rudd (philosophy, biology '83): the Virginia Tech Sustainable Water Undergraduate Research Fund and the Virginia Tech Sustainable Water Scholarship.

"Water is one of the most important fields of the 21st century," said Rudd. "The field offers a vast range of opportunities for work and study, such as establishing policies and engineering processes to conserve and recycle water, researching supply and consumption to assess the cost of water, and crafting strategies to help resolve stakeholder conflicts about ownership and use of water. The degree bridges the gaps between science and policy and theory and practice—and Virginia Tech is leading the way."

Hanna-Attisha's findings underscored the direct impact on the health of children, whose developing bodies are especially susceptible to the dangers of lead, and accelerated the public health response: Genesee County and Flint officials declared public health emergencies, while Michigan Gov. Snyder announced $1 million in state funding for water filters in Flint (24,000 were handed out), along with immediate testing at city schools, expansion of lead testing for individuals, and expediting treatment of Flint water to control pipe corrosion. Snyder soon announced a multimillion-dollar plan for reconnecting Flint to Detroit water.

Guyette called the Flint situation the most meaningful project of his journalism career. "It's kind of a double-edged sword in some ways. At the root of this is a tragedy: kids needlessly lead-poisoned. That is the dark shadow hanging over all of this. But on the other hand, Marc, the students at Virginia Tech, the grassroots activists in Flint, me with my reporting—what we did do was stop [the tragedy] from going forward."

The Tech team found themselves positioned to tackle a tremendously complex situation that stretched across traditional academic boundaries. Research scientist David "Otto" Schwake said the team's involvement went far beyond the basics. "It's not just engineering. It's not just the water industry. It's not just public help. It's also very much socioeconomic and political. The whole situation came about because of a lack of funds and decisions by government agencies. There's also the social justice factor: that Flint is a very poor city with a lot of minorities and [did not have] the best water quality to begin with."

Underlying all of those factors is the human element. At a supper in Flint, civil engineering Ph.D. student Rebekah Martin asked a pair of activists about their motivation. "They said, 'This is our home,'" Martin recalled. "'We're not going to let our families be walked over and not heard when they're being poisoned.'" The sentiment points back to the first canon of civil engineering—to protect the public. "As engineers," Martin said, "a lot of times we sit in offices and design things. Or you may have some formula that goes into treating water or designing a system to treat water, but you don't talk to the people who drink that water or who will be affected by what you're designing. It's important to get out there and listen to people."

Edwards said Flint was a perfect example of how science failed at first, and science-based advocacy worked—and worked quickly. But because he has seen history repeat itself, he is realistic and cautious. "We are capable of learning something, but I'll believe it when I see it. … As long as lead pipes are there [in cities across the country], it's a time bomb waiting to go off."

In the Engineering Ethics and the Public course, Edwards and Lambrinidou help students understand who they want to be when—not if—they face an ethical dilemma. And as Edwards told the Goodwin Hall crowd, society must set its priorities to repair crumbling infrastructure, and individuals must display the courage to stand up and take action.

Said Edwards, "I maintain that people are born heroic."

Heroism can surface anywhere—in Flint residents or in a Blacksburg classroom.

"You don't have to run for president. You don't have to be a Nobel laureate," Ph.D. student Pan Ji said during the Goodwin Hall presentation. "You can just be a normal person fighting for a just cause."

For more on how Virginia Tech approaches complex societal problems within its areas of excellence, such as water, visit Beyond Boundaries →

Timeline

Marc Edwards, TEDxVirginia Tech, 2013