|

A forensic scientist stalks through a crime scene, brows furrowed, slowly scanning the area for evidence. Suddenly, he squats and picks up a minute fragment of cloth. With one gloved hand, he holds the evidence up to the light and announces, "I think we have our killer."

Although this could be a scene from one of many popular television shows about forensic science, such shows are geared more toward entertainment than accuracy. The reality of the field, however, is just as interesting and varied -- or so say some of the 18 known Hokies currently working for Virginia's Department of Forensic Science (DFS).

Creative license

Not to be a killjoy, says Quality Assurance and Safety Coordinator Fred Frederick (Ph.D. chemistry '83), but "in Virginia, our scientists' jobs aren’t as flashy as those on television. We're not part of law enforcement so, with very few exceptions, our examiners don't go to crime scenes, and certainly never until they're secure -- none of our employees is 'packing heat.'"

In fact, Frederick adds, "The 'lab geeks' are actually the characters who more accurately portray our scientists' roles."

The true image of a forensic scientist is only the first of many differences between the television dramas and real life. To John Przbylski (biology '96), a controlled substances examiner, the greatest inaccuracy is the depiction of speedy evidence analysis. "On the shows, a sample suspected of containing a controlled substance is simply injected onto a gas chromatograph and, 'Voila!' Two minutes later, the instrument is spitting out a piece of paper that identifies the substance," he says. "In real life, the process is significantly more involved."

Indeed, time is not on the side of forensic scientists. Frederick notes that "with the exception of extremely high priority cases, examination of most evidence does not begin until a few months after it is received."

As well, he says, the evidence doesn’t reveal quite as much as television might have you believe. "Identification of a latent fingerprint in a database does not call up a photo, home address, and place of employment on the computer monitor, nor does an instrument analyzing a paint particle have the ability to display the number of vehicles in the area with that type of paint."

Lest the veil of entertainment be completely lifted, the scientists do agree that, for the most part, the shows do accurately reflect the examinations, instruments, and methodologies commonly used. Forensic biology examiner Kevin Flint (biology '00) also credits the shows with providing "an excellent public awareness to the growing field of forensic science. I imagine that if they portrayed the science with 100 percent accuracy, it would not be as exciting for the general public as it is for me."

Joining the public in enjoying the shows is controlled substances examiner Shannon Buskirk (chemistry '99), who admits that she is probably one of the few forensic scientists who do. "I usually find the stories pretty interesting and just giggle a little when they do something crazy, like picking up a piece of evidence after taking only one precursory photo."

So . . . what do they do?

Virginia's DFS is comprised of four labs: the Central Lab in Richmond, the Northern Lab in Fairfax, the Western Lab in Roanoke, and the Eastern Lab in Norfolk. Although the department encompasses 10 forensic science sections -- plus the Forensic Training Section, which trains law enforcement officers across the commonwealth -- one section is often in the national spotlight: Forensic Biology, better known as the home of the state's pioneering work with DNA.

In 1994, Virginia became the first state to primarily use DNA in its forensic biology analysis and, a decade later, made national headlines when then-Gov. Mark Warner ordered DNA testing in dozens of old cases to determine if prisoners convicted of violent crimes would be exonerated by modern analysis of evidence. Warner also ordered the first-ever post-execution DNA review of the case of Roger Keith Coleman, who was put to death in 1992 for murdering his sister-in-law; the test confirmed Coleman's guilt.

Just two years ago, the state's DNA Databank -- comprised of previously convicted offenders and individuals arrested for specific crimes -- made its 2,000th "hit," which is when a DNA profile based on evidence is matched to a person in the database. As of May 31, the database had scored 3,391 hits.

What do such staggering statistics translate to on a day-to-day basis? A varied workload, says forensic biology examiner Eve Rossi (animal science '97). "I might spend one day screening cases, which means I will be looking at pieces of evidence for the presence of a particular body fluid," she explains. "Other days, I might be conducting DNA analysis to determine if a person is eliminated or included from a piece of evidence."

Like most forensic examiners, Rossi also writes reports of her findings, reviews case files, and testifies in court as an expert witness. "It certainly can be stressful because a lot of cases enter our door every day, but it is also gratifying to feel that I might be helping solve a crime," she says.

Frederick points out, however, that although "DNA makes many more headlines, the department is a front-runner in all areas." And casework in the other sections is just as complex.

In Firearms and Toolmarks, for example, Jay Mason (forestry and wildlife '78) -- who supervises that unit at the Northern Lab -- says that in a typical case, examiners may determine a firearm's make, model, caliber, and operability; conduct test-firings to compare microscopic markings on the test bullets to those on bullets from a crime scene; analyze a victim's clothing to identify entrance and exit bullet holes; and look for gunshot residues to gauge the distance between the victim and the muzzle of the gun. Yet it's not all guns and aim in the Firearms and Toolmarks Section, which also investigates burglary cases by examining locks, tools, and toolmarks; and vehicle accidents by matching automobile parts and determining the speed of impact and whether headlights and taillights were operating at the time of impact. Of his job, Mason muses, "I think of myself as a professional puzzle-solver."

Similarly learning to solve puzzles is trainee Chad Schennum (biology '01), who, in Trace Evidence, observes and assists other examiners with casework and is gaining experience with the lab's sophisticated instruments. "We use an ion chromatograph to separate and identify ions that may be present in a sample, such as sulfate, nitrate, potassium, and sodium," Schennum elaborates. "The X-ray diffractometer helps us identify unknown crystalline materials. And the Fourier transform infrared spectrometer uses infrared light to identify a wide range of substances by indicating their chemical structure and makeup."

Using similar instrumentation to test evidence in Controlled Substances are Przbylski—group supervisor of the Central Laboratory's section -- and Buskirk. "In drug analysis, we typically use screening tests that give us an indication of the identity of the sample, and with these results, we use more definitive examinations to conclusively identify it," Burskirk explains.

To ensure that analyses from the four DFS labs are accurate, reliable, and admissible in court, Frederick oversees compliance with the state's standards and regulations for all laboratory quality assurance and safety policies and practices. In addition, Frederick -- who notes that he would never complete all of his work without his "able assistant," Carolyn Sexton Schrider (biology and health physics '81) -- administers approximately 300 tests annually for the department's Proficiency Testing Program, in which each forensic scientist and most technical support staff members are given at least one mock case to examine.

True stories

When crime investigation shows advertise that an episode is "ripped from the headlines," the featured case may indeed be based upon the work of DFS scientists.

"I have worked on several high-profile homicides and sexual assaults -- and by high profile, I mean cases that have received extensive media coverage," says Rossi. "There is an extra bit of gratification that comes from working on these cases and feeling that I really may have made a difference, whether it is helping to identify a suspect or providing results that may aid in the prosecution of a heinous crime."

Mason, an expert witness in more than 400 cases during his 24 years as a forensic scientist, has worked on several high-profile investigations, including assisting at two of the Virginia crime scenes during the 2002 sniper shooting spree. As well, at the request of the U.S. Department of Justice, he reviewed all firearms evidence, documentation, and trial transcripts from the investigation into the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in order to determine whether additional testing of the evidence could help answer some remaining questions.

"More often than not, we are scientifically proving what the investigators already know or suspect," Mason says. "Occasionally, we are able to discern information from a piece of physical evidence that changes the direction of the investigation or provides the break necessary to solve a cold case -- these are the cases that are personally the most rewarding."

The examiners in Controlled Substances have found that their cases tend to be region-specific. For instance, in the Richmond area, says Przbylski, the two most common drugs they identify are marijuana and cocaine. In the western part of the state, however, forensic scientists see more methamphetamine cases.

Przbylski also notes that the drug du jour tends to vary over time. "Thirty years ago, barbiturates were a common drug of abuse, whereas now, they are submitted only on rare occasion," he says. "Certain drugs that are popular today may not be several years from now due to such factors as availability and government control."

The foray into forensic science

Traditionally, there are two paths to becoming a forensic examiner at DFS. One is to attend the Virginia Institute of Forensic Science and Medicine (VIFSM) program -- as did Buskirk and Flint -- in which students are trained by certified forensic examiners at DFS.

Buskirk, who completed her training as a drug examiner in a little less than a year, learned to analyze controlled substances and worked alongside forensic scientists on real cases. Several mock cases also prepared her for testifying in court.

Flint, who completed his year-long training in forensic biology last September, received similar training in his DNA analysis and casework. "The most beneficial aspect of the program was the direct instruction from and access to highly experienced forensic scientists," he notes. "Other programs can teach the science, but the hands-on experience was incredibly beneficial."

The other path into DFS is to enter the department at the trainee level and undergo a departmental program, which offers the same type of instruction as VISFM, including the hands-on experience with real cases.

Schennum, who graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) with his master's degree in forensic science, chose this route into DFS and began the program last September. Currently, he is learning explosives analysis, which he hopes to complete this summer, after which he will move to fire-debris analysis.

At the end of the program, Schennum will be required to appear before a panel and discuss a subject relevant to his training, much as in a thesis defense, minus the thesis, he says. Then he will testify in a mock trial about his final practice case, which gauges whether "trainees can explain what they did and why in a manner that can be understood by a jury of laypersons."

Finding the motive

Why did these Hokies choose such a fascinating field? Not surprisingly, each alum had a unique impetus.

Rossi, for example, had just started working on her post-graduate degree in animal science in 1998, when interest in forensic DNA was just starting to surge. "We had just seen the O.J. Simpson case and it really started to get people interested in using DNA as a tool to help solve crimes," she recalls. After exploring "this new and exciting field of science," Rossi entered the VIFSM program.

On the other hand, Mason spent three years as a Virginia state game warden and had employed the state's forensic services to investigate several cases. He discovered that the field intrigued him and when he was offered the chance to train as a forensic scientist in Firearm and Toolmarks, Mason knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. “Being inquisitive by nature and mechanically inclined -- and having had a lifelong interest in firearms and the criminal justice system -- made the transition an easy one," he says.

Przbylski had less direction -- a year after graduating, he was still unsure what he wanted to do with his biology degree. Although he views the "CSI" programs with disdain, television shows about forensic science sparked his interest, he says, hastening to point out that he is "speaking specifically of shows on The Discovery Channel and TLC that accurately portray the field." In the fall of 1999, Przbylski entered VCU's forensic science graduate program and the rest, he says, is history.

It was history, in fact, that led Schennum into forensic science. "My original goal was to become a paleontologist and dig up dinosaurs for the rest of my life," he says. While he was at Tech, however, his interest in paleontology began to wane. During his senior year, Schennum took a DNA class in which he learned about forensic science, but even though his interest was piqued, he couldn't completely give up on paleontology at that point. After graduation, Schennum took a job as a research assistant at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. "I found that it wasn't really for me, so I started looking into forensic science graduate programs."

A class at Tech also lured Flint into forensic science. En route to his degree in veterinary medicine, he took Biotechnology in a Global Society, which introduced him to the use of DNA in forensic science. "This led to a growing interest in DNA technology and the realization that I could help make a direct impact on my surrounding community," Flint recalls.

Unlike her fellow Hokie examiners, Buskirk knew that she wanted to work in forensic science before she hit college. When she was in high school, she says, her mother recommended a book by Patricia Cornwell featuring a fictional state medical examiner for Virginia and her work in forensic science. "I was already interested in math and science, especially chemistry, so after reading Cornwell's books, which tend to give a more technical spin on 'murder mysteries,' I became intrigued by the field of forensic science," Buskirk explains. "By my senior year of high school, I had pretty much made up my mind that forensic chemistry was what I wanted to do."

Despite their different paths and specialties, it's evident that the Hokies working for DFS share a love for their jobs. Their collective sentiment may best be summed up by Schennum: "This is easily the coolest job in the world. My wife is tired of me saying this, but I don't work a day in my life."

|

|

Forensic biology examiner Kevin Flint '00: Forensic biology examiner Kevin Flint '00:

"I imagine that if they portrayed the science

with 100 percent accuracy, it would not be as

exciting for the general public as it is for me."

|

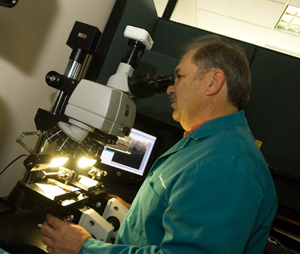

Kevin Flint '00 examining a fabric. Kevin Flint '00 examining a fabric.

|

DNA samples are carefully analyzed. DNA samples are carefully analyzed.

|

Kevin Flint '00 in the lab. Kevin Flint '00 in the lab.

|

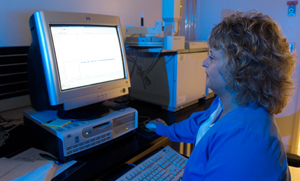

Vickie Miller '81, who works in Controlled Vickie Miller '81, who works in Controlled

Substances at the Western Lab, examines

the results of a drug-screening test.

|

VIFSM student Derek Price '05 examines a controlled substance as part of his training. VIFSM student Derek Price '05 examines a controlled substance as part of his training.

|

Chad Harris '99 works in DNA Chad Harris '99 works in DNA

at the Western Lab.

|

Van Roberts discharging a gun for testing. Van Roberts discharging a gun for testing.

|

Van Roberts at the Western Lab. Van Roberts at the Western Lab.

|

Andy Johnson gathers evidence from a boot. Andy Johnson gathers evidence from a boot.

|

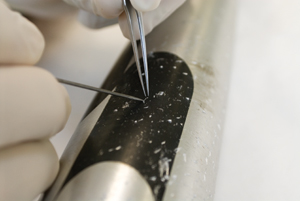

Anthony Brown removes fragments Anthony Brown removes fragments

from a baseball bat for testing.

|

|

|

HOKIES are on the case

Currently, 18 Hokies are known to

contribute to the renown of Virginia's

Department of Forensic Science:

Henry Bateman

(M.S. biology '73)

Forensic Toxicology

Shannon Buskirk

(chemistry '99)

Controlled Substances

Thomas Dewan

(business administration '64)

Questioned Documents

Matthew Farr

(biochemistry '98)

Forensic Biology

Kevin Flint

(biology '00)

Forensic Biology

Lloyd Fox

(biology '79)

Trace Evidence

Fred Frederick

(Ph.D. chemistry '83)

Quality Assurance and Safety Coordinator

Chad Harris

(environmental science '99)

Forensic Biology

James Lavery

(psychology '94)

Information Technology

Julien (Jay) Mason Jr.

(forestry and wildlife '78)

Firearms and Toolmarks

Corrie (Oberdorf) Meyer

(chemistry '92)

Controlled Substances

Vickie Miller

(biology '81)

Controlled Substances

Derek Price

(chemistry '05)

Controlled Substances

John Przybylski

(biology '96)

Controlled Substances

Eve Rossi

(animal sciences '97)

Forensic Biology

Chad Schennum

(biology '01)

Trace Evidence

Carolyn Sexton Schrider

(biology and health physics '81)

Quality Assurance and Safety

Todd Yoak

(biochemistry '00)

Controlled Substances

|

|

|