Virginia overflows with historical sites, from the pioneering inventiveness of Thomas Jefferson's Monticello to the catchy bluegrass music of Southwest Virginia's Crooked Road. But for many, the commonwealth's greatest asset is the natural bounty and beauty of the Chesapeake Bay.

President Barack Obama reaffirmed the importance of this environmental asset when, in 2009, he signed an executive order declaring the Chesapeake Bay a national treasure and directing federal agencies to coordinate and accelerate the restoration process. Obama's order is an attempt to bring the state and federal governments into compliance with the Clean Water Act of 1972.

SETTING THE MARK

As the bay's brackish water glints sharply in sunlight, a wealth of trouble lies beneath the surface: eutrophication, which involves an overabundance of nutrients and sediments that degrade water quality and clarity and create algae blooms, depleting the oxygen necessary for a thriving aquatic life scene.

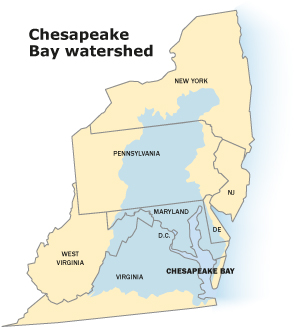

The Chesapeake Bay watershed stretches through parts of six states and the District of Columbia. Most pollution doesn't begin on the Eastern Shore or the Coastal Plain bordering the bay, but rather originates inland.

The Chesapeake Bay watershed stretches through parts of six states and the District of Columbia. Most pollution doesn't begin on the Eastern Shore or the Coastal Plain bordering the bay, but rather originates inland.

Though the Chesapeake Bay Initiative began in the 1980s, the restoration has been a long, slow process. Despite cooperation among the states in the watershed, the program is far from meeting its bay-restoration goals. In the Chesapeake 2000 Agreement, the states banded together to lower pollution in the bay and improve water quality. By 2008, however, they had met only 21 percent of those goals, according to the Chesapeake Bay Program's website.

That's where Obama's mandate enters the scene. For the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and bay watershed states are setting Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that define how much of a given pollutant the bay can tolerate--what the EPA calls a "pollution diet" for the bay. With the advent of TMDLs, officials hope to reduce nutrient and sediment pollution through a combination of regulatory and voluntary measures, keeping those nutrients out of the waterways before they enter the bay.

A number of Virginia Tech researchers are playing vital roles in this process. Saied Mostaghimi, associate dean for research and graduate studies in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the H.E. and Elizabeth F. Alphin professor in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, serves on the executive board of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) for the Chesapeake Bay Program. The committee provides scientific and technical guidance to the Chesapeake Bay Program on measures to restore and protect the bay.

In a related area, Tamim Younos, associate director of Virginia Tech's Water Resources Research Center (WRRC), leads a multi-institute academic advisory committee that is devoted to helping the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) establish water-quality standards for Virginia. The committee's goal is to analyze the data collected by the DEQ to help the agency set nutrient standards for Virginia's streams and rivers by 2011. While standards for other pollutants, such as bacteria, are already in place, no such benchmark exists for nutrients. These standards will greatly improve the health of the Chesapeake Bay.

"There's no easy solution," says Younos, "but our job as a university is to come up with a science-based solution that's also practical and cost-effective."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MORE about the BAY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The EPA has already promoted the use of five cost-effective measures to reduce human effects on the bay: wastewater treatment upgrades, diet and feed adjustments for livestock, cover crops to prevent soil erosion in winter, conservation tillage to minimize soil disturbance, riparian buffers, and traditional and enhanced nutrient-management plans. In place since 1985, these and other restoration efforts have reduced human impacts on the bay, but not nearly enough, says Jim Pease, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics. Pease is also a member of STAC and of multi-state Extension groups working to provide education on cost-effective pollution controls.

One of the biggest detriments to bay health is population growth, which results in an increased need for food production and for land development, which inflates the volume of wastewater and lawn fertilizer runoff.

Some solutions are relatively small and site-specific, such as fencing to keep cattle out of streams, preventing erosion of stream banks while keeping waste from going directly into the waterways, or teaching landowners how to apply the proper amount of lawn fertilizer.

Other solutions are technology-based, such as the work of Jactone Ogejo, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, whose research focuses on nutrient recovery, finding ways to concentrate excess nitrogen and recover phosphorous from manure. "Manure has more phosphorous and nitrogen than the crops can use," says Ogejo. "One of the ways of looking at the continued use of manure as a fertilizer is to make 'designer' manure in which the nitrogen and phosphorus is made available according to the need of crops. The phosphorus recovered or removed in the process can be transported for use in locations that have phosphorus deficits."

While many changes and technologies target the individual or local level, other research takes more of a large-scale approach. Courtney Reijo, a graduate student working on her master of science in forestry, is doing research using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to determine the most effective places to locate riparian buffers, areas of trees or other vegetation planted next to streams and creeks that prevent soil erosion and act as natural filters of nutrients.

These buffers perform many ecosystem functions, says Reijo, including sediment reduction, nutrient removal, wildlife habitats, and stream temperature control. Reijo is using GIS to evaluate topographic influences on the riparian zones' nutrient removal throughout the entire bay watershed. By determining the places in the landscape where riparian buffers are most effective, the research will help officials select the best places to concentrate their energy and resources.

"We're trying to use natural means to fix these problems," says Kevin McGuire, a research assistant professor for the WRRC, who also serves as Reijo's advisor on the project.

UNLIKELY TREASURES

Just as rainforests may hold undiscovered sources for treating disease and improving the human condition, the Chesapeake is home to a critter that proves invaluable to our everyday lives: the horseshoe crab.

"They're really critical to the near-shore ecosystem," says Eric Hallerman, professor and head of the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences and director of the Horseshoe Crab Resource Center. Aside from playing an important role in the food web by serving as prey for fish and birds, particularly in the early life stages, the horseshoe crab is vitally important to humans as well. Their blood contains limulus amebocyte lysate, a chemical commonly known as LAL.

Almost every person in the developed world has benefited from LAL, which is used to detect endotoxins in vaccines and implantable medical devices. The crabs don't rely on antibodies to fight illnesses; instead they have broad-spectrum resistance to bacteria. "Horseshoe crabs have been around for 200 million years, so they've seen everything," says Hallerman. "LAL can see the widest range of bacteria of any chemical that we know." Though other types of crabs are harvested in other parts of the world for LAL, the horseshoe crab is the most prized for this use.

|

|

|

|

|

Tangier Island, nestled in the heart of the Chesapeake Bay

|

|

|

|

Hallerman has devoted most of his research to monitoring and conserving the horseshoe crab population. For these crabs, the biggest danger comes from overfishing. People have been harvesting horseshoe crabs for centuries. They served as a food source for Native Americans and were used by European settlers as fertilizer well into the 20th century.

In 1999, the government placed restrictions on the number of crabs that could be harvested, especially female crabs, in hopes of rebuilding the population. Hallerman says the numbers are creeping up. "I want these populations to rebuild. … I want there to be abundant horseshoe crabs when my great-grandchildren walk down the shores of the bay."

It's not just the horseshoe crab that makes the bay a natural gem worth preserving. The bay is famous for soft-shell crabs and oysters that many treasure as delicacies, and game fish, such as striped bass and bluefish, often lure anglers to its deeper waters. "There are a huge number of fish and oysters that are affected in different ways by pollution," says Pease.

What makes the bay and its watershed so important, Pease adds, isn't just that it is a water source, but the "ecosystem services" that water provides to people across the watershed, from fishing and canoeing to witnessing wildlife and hiking near streams and rivers. "Those things are generated by land uses we want to preserve as a society."

"Everyone is a stakeholder when it comes to water," notes Younos.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia master naturalists teach the public about rain barrels and rain gardens; planting riparian buffers; and bayscaping, a form of landscaping.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Michelle Prysby, coordinator of the Virginia Master Naturalist Program, has seen firsthand the value of engaging citizens in both stewardship and hands-on education. With 850 active volunteers, the program consists of educational projects, citizen science projects such as surveys and monitoring, and stewardship.

Master naturalists teach the public about rain barrels and rain gardens; planting riparian buffers; and bayscaping, a form of landscaping in which landowners plant native plants instead of traditional lawns, thereby using less water and fertilizer. They also lead excursions for youth as part of the Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience (MWEE) program. "Research shows that engaging students in these field experiences makes them more likely to act to protect the bay in the future," says Prysby.

She adds that these experiences are important for both youth and adults. "When people don't get to be outdoors and see the natural resources and wildlife that we have in the bay watershed, they don't feel as inclined to participate in conservation efforts," she says.

Buoyed by the hard work of Virginia Tech faculty members and others from all levels of government, from local to federal, restoration is still a slow process--and it can take decades before water quality improves. "We have to get down to the individual and local level," says Pease. "The question has to be there every time, 'What is going to be the impact of [this action] on the bay?'"

From the small scale to the big picture, experts at Virginia Tech are helping to ask those questions, to restore and preserve a national treasure that belongs to everyone.

Those interested in the Virginia Master Naturalist Program should visit www.virginiamasternaturalist.org to learn more or to enroll in a basic training class.