FEATURE

Able to change and adapt without compromising its functional integrity, Silly Putty epitomizes the concept of plasticity. Replace the popular toy with 100,000 miles of blood vessels, millions of years of evolution, and billions of neurons and even more synapses, and the result is one of the most complicated and malleable arrangements of matter known to humanity: the brain.

"Brain plasticity" is a buzz phrase that conjures up excitement, particularly among baby boomers who are nearing a stage in their lives when brain function has already begun to decline. After all, who doesn't want to believe the brain can learn anything at any age?

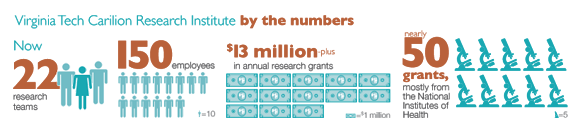

"The brain has a profound ability to adapt to challenges over a life span," said Michael Friedlander, executive director of the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, which is comprised of more than 20 world-class research teams that address some of the major health issues in contemporary medicine. "We can say that the brain is plastic at all stages of life, but we must remember that, as we get older, its capacity for plasticity changes and in some ways declines."

Friedlander said those challenges occur more frequently than people might realize.

"All brain disorders combined—including stroke, Alzheimer's disease, traumatic brain injury, depression, addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder, Parkinson's disease, and developmental and intellectual disabilities such as autism spectrum disorders—have a greater economic impact on the country and the world than any other type of disorder, and that includes cancers and heart disease," he said.

Now in its third year, the research institute creates a bridge between basic science research at Virginia Tech and clinical expertise at Carilion Clinic and increases translational research opportunities for both partners in a unique public-private endeavor that also includes the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. Many of the current research teams at the institute are dedicated to the brain: its influence on all aspects of our bodies and our behavior, its adaptive capabilities, and, in certain instances, its potential for training and retraining.

In high-powered labs at the institute, researchers examine components of the human brain that can easily stretch the limit of one's imagination. For instance, Stephen LaConte, an assistant professor at the institute and at the Virginia Tech-Wake Forest School of Biomedical Engineering and Sciences, helps people who have a mild traumatic brain injury such as a concussion rebalance their default mode network, a network of regions in the brain that seems to be connected to non-taxing mental tasks such as daydreaming. The default mode is believed to become disrupted when the brain is injured, causing delays in recovery.

LaConte observes the participants' brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive imaging method that measures brain activity. A computer screen is projected so that participants can see it while they are in the machine. On cue, the participants move an arrow on the screen simply by thinking about the task.

Unbelievable? Paranormal? It may seem so at first glance, but LaConte explained.

"We use an innovation for fMRI that we developed and call ‘temporally adaptive brain states,'" he said. "Using three-dimensional movies of the brain, we extract in real time what the brain is doing mid-thought. This is the opposite of the usual goal of neuroimaging, which is to map what's going on in the brain while the person is doing something."

Think of this process as biofeedback on steroids. Such feedback might help LaConte's study participants rebalance their default mode network for better brain health and function.

"Many things happening in our brains are not accessible to us consciously," LaConte said. "With fMRI, we can potentially see internal processes and give people conscious access to things that they are either minimally aware of or completely unaware of."

Not surprisingly, in light of its cutting-edge methods, LaConte's research has many potential applications, such as the rehabilitation of people with neurological and psychiatric diseases.

Brooks King-Casas, an assistant professor at the institute and in the College of Science, studies brain function in the context of social interaction, examining how the brain makes decisions. By studying such factors as the regions of the brain and chemical and neurobiological events, he can provide computational models of various brain processes, including trust and anger, and how psychiatric illness can impact these processes.

In a study funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, King-Casas is examining post-traumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury among returning veterans.

"People who have experienced major stressors often have difficulties with anger and aggression and regulating their emotions in certain social situations," he said. "We are interested in how stressful experiences affect how people make decisions in both social and nonsocial contexts."

"The human brain is born very underdeveloped compared to the brains of some other mammals. It continues to develop for many years after birth. It is exquisitely sensitive to environmental inputs during the explosive period of synapse formation and refinement that occurs during the early years," Friedlander said. "Millions of synapses between neurons and nerve cells are selectively eliminated, strengthened, refined, and expanded. The brain is very busy during development, and thus the mechanisms of plasticity that undergird learning are the subject of intense scientific scrutiny."

Research in Friedlander's lab is directed at revealing the physical changes that occur at the synaptic connections between individual brain cells during learning. The research compares these processes in normal developing brains with those in injured brains.

"Synapses are the fundamental computational elements of the living brain," said Friedlander. "They are the sites where learning occurs and memories are initially formed. Many brain disorders are the result of impaired synaptic function, often leading to intellectual disabilities, aberrant behavior, or poor memory. The synapse is where the action is for healthy brains and disordered brains alike. They provide an incredible opportunity to understand how memories are formed and to apply this knowledge to help overcome some of the most devastating neurological and psychiatric disorders."

Other institute scientists are dedicated to the fascinating aspects of brain development. What are the biological underpinnings of empathy? Are there noninvasive ways of performing deep brain stimulation for patients with such ailments as Parkinson's disease and depression?

Sharon Ramey, a distinguished research scholar at the institute and a research professor of psychology in the College of Science, and her colleagues at the Neuromotor Research Clinic—which is co-directed by Stephanie DeLuca— are studying highly intensive forms of therapy to promote motor function in children with cerebral palsy and other brain injuries.

Using a method of therapy previously used on adult stroke patients, the team restrains the child's "better" arm with a lightweight flexible cast, prompting the child to start using the "weaker" arm and hand for everyday activities. During the time-intensive therapy sessions, the child learns new skills and movement patterns.

"What has been very exciting about this is that we see rapid and large changes in almost all the children," Ramey said. "We want to find out to what extent this therapy leads to a reorganization of the brain—in terms of voluntary motor control, sensory perception, and even cognition and motor therapy."

With funding from the National Institutes of Health over the next five years, Ramey's team, along with colleagues at the University of Virginia and The Ohio State University, will treat and study 135 children, ages of 2 to 8, using four versions of the therapy. The study, the first of its kind to follow participants for one year after treatment, aims to find the most efficient and effective treatment for different types of children.

"We can't think of a better place to do this study," Ramey said. "Having the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute with its Human Neuroimaging Laboratory here in Roanoke, combined with a regional clinical population, make this ideal. Our dream is that soon, this form of therapy will become widely available to all children who could benefit."

Until now, there hasn't been a way to measure a person's mental health in a computational manner, such as the way lipids and cholesterol are measured for heart disease, and blood sugars are measured for diabetes. Read Montague, a professor at the institute and in the Department of Physics in the College of Science, is changing how mental health is physically assessed. "I am a computational neuroscientist," he said. "I turn feelings into numbers."

As director of the Human Neuroimaging Lab, Montague leads a group of social-cognition researchers at the institute who study people's awareness of social interactions. "Social cognition is equally if not more important than parts of our regular cognition, such as intelligence and memory, because it involves basic things that are important to survival," Montague said. "The brain had to develop social cognition early on in its evolutionary history."

Montague uses various approaches to brain imaging to study both healthy and diseased brains and how people interact socially.

"Throughout the course of evolution, humans had to be able to deal with other people in a variety of ways," Montague said. "We had to be able to anticipate and model their likely behaviors because they were often the most dangerous elements in our environment."

One of Montague's research areas utilizes social-exchange experiments that typically feature games in which participants engage in some sort of economic exchange. The games measure participants' levels of risk-taking, trust, and rewards.

As a particular game is played, each participant's brain is monitored by an fMRI for physical signals that are mediating the process. Montague and his research team then use these computational models of healthy brains in social interaction to help understand how people diagnosed with neuropsychiatric conditions—such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, borderline personality disorder, and major depression—interact during similar social-interaction games. Ultimately, the knowledge gained from this research will be used in the diagnosis and treatment of these and other disorders.

Montague also directs the Roanoke Brain Study, a project aimed at understanding decision-making through the life span and its relationship to brain development, function, and disease. Designed similarly to the Framingham Heart Study, a highly regarded longitudinal study that has significantly informed how doctors and researchers view the heart, the brain study will use functional imaging, genetic analysis, and behavior to uncover key aspects of human brain. The study will be the world's largest lifespan study of the brain, drawing in thousands of participants from the Roanoke area and several sites in London.

"We know that higher cognitive function has been under selection pressures for a long time," Montague said. "Functions such as memory and the ability to anticipate the future, to regulate one's emotional states, and to make references to things are all part of the cognitive behaviors that distinguish humans from other creatures on the planet that share mammalian brains with us."

Until now, cognition related to decision-making has not been studied on the scale that Montague and his team hope to realize. "By doing such a large-scale study, we ought to be able to start making statements about a connection between people's cognitive function and their genetic makeup," Montague said.

Montague said he hopes the study will serve as an open source of data for brain researchers around the world. Those interested in volunteering for the study may visit http://research.vtc.vt.edu/volunteer.

Produced by University Relations