AROUND THE DRILLFIELD

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 not only banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, but helped open the doors of Virginia Tech to a more diverse student population.

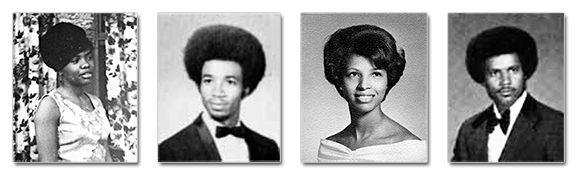

Commemorating the landmark legislation's 50th anniversary as part of Virginia Tech's Black Alumni Reunion weekend in March, a webinar broadcast from the North End Center featured four of Virginia Tech's first black students, who spoke about their experiences integrating the university in the late '60s and early '70s. Their stories were by turn frustrating, humorous, emotional, and ultimately inspiring.

Linda (Edmonds) Turner (clothing, textiles, and related arts '70, M.B.A. '76, Ph.D. general business '79), James Watkins (biology '71), and La Verne "Freddie" (Hairston) Higgins were among the first black students to attend Tech, while Calvin Jamison (health and physical education '77, M.A.Ed. student personnel services '81, C.A.G.D. '86, Ed.D. '88) attended during a time when the university was actively working to increase student diversity.

The first black student to attend Tech was electrical engineering major Irving Peddrew III in 1953. The first black graduate was Charlie L. Yates (mechanical engineering '58), and the first black female graduate was Linda Adams Hoyle (statistics '68). Watkins, Turner, and Higgins all arrived at Tech in the late '60s, when there were still only a few dozen black students on campus—and that included exchange students from Africa.

Turner and Higgins also carried the distinction of being among the first women students at Tech. Higgins recalled that when she arrived there were about 350 female students, 42 black students (including those from Africa), and only six black female students.

"It was really difficult being not just black but female," Higgins said. "The institution was not prepared to deal with us."

As they were often the only black student in a given class, they frequently drew unabashed stares from their classmates. Watkins remembered sitting at a cafeteria table with white students, only to watch them get up and move. His freshman year, the only two black students paired with white roommates in the dorms saw the white students move to different rooms.

Athletic events added to the challenges: Games at Cassell Coliseum were accompanied by displays of Confederate flags and the singing of "Dixie," which at the time served as an unofficial fight song.

Turner described a pep rally during which students marching around campus set a representation of the letters "VT" ablaze. The "V" fell off, leaving a fiery "T" that struck Turner as looking like a cross. Even though unintended, the image triggered a visceral reaction in Turner. "I didn't go to another pep rally," she said. "People didn't understand why ‘Dixie' and those things could be upsetting."

Another flashpoint was the student response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the spring of 1968. Watkins said he was amazed by how many Tech students attended a memorial in support of the fallen civil rights leader—"the Drillfield was packed"—but that feeling turned to shock when a small scuffle ensued between dueling groups of students over whether to position the American flag at half- or full-staff.

Watkins said those situations resulted in his black dormmates making a pact their freshman year to transfer out of Tech—but by graduation, most had stayed and didn't want to leave.

How did they make it through? By finding mentors, support groups, and each other.

For Watkins, the formation of Tech's first black fraternity, Groove Phi Groove, made all the difference. The group provided him with a community of support and an outlet for social gatherings that included black students at nearby Radford University.

"You have this bond with people," said Watkins, who became the first black president of the Virginia Dental Board in 1992 and is a general practice dentist in Hampton, Virginia. "You have something that makes it feel like you were wanted, and that was a very positive experience having the relationships that Groove Phi Groove provided."

Turner, meanwhile, developed relationships with mentors. Jean Harper, then-dean of Tech's College of Home Economics, hired Turner for office work, put her in contact with the university's movers and shakers, and convinced Turner to come back to Tech to obtain her Ph.D. Turner went on to complete a post-doctoral fellowship at Harvard University and has served as vice president and chief marketing officer for Dean College, and president of the Urban College of Boston and Roxbury Community College, all in Massachusetts.

Higgins, who was Turner's roommate during freshman year, said she found support particularly through Tech United Ministries. There, she met like-minded activists, including her first husband. She now works as associate dean of the business college at Eastern Michigan University.

Higgins didn't shy away from making her voice heard during those politically turbulent years of the late '60s. With a white student, she co-wrote a feature, "Back Talk," for the campus newspaper. In the column, the two debated issues such as the Vietnam War, labor unions, and mixed-race dating. The events of 1968, however, exhausted her. She soon left Tech and moved to Minnesota.

"I was really tired of fighting that battle in the South," Higgins said. "I felt like I had done my part and needed to relax to keep my sanity."

Jamison said that when he arrived after the first wave of black students, Tech was home to a relatively small black population. In one class of 350 students, Jamison was the only African American. When he missed a class because of a death in the family, the professor noticed and singled him out. Jamison used the incident as an opportunity.

"From that day on, when I went to a class, I went to the front row and met the teacher," Jamison said. "I encouraged all the students I [later] worked with to do the same thing. This approach was very beneficial to them in enhancing their educational experience. … My approach is simple: ‘It is an opportunity. Make the best of it.'"

Jamison joined Groove Phi Groove as an undergraduate, and later became president of the Human Relations Council (now the Black Student Alliance). When he graduated, he was hired as assistant director of admissions and was instrumental in increasing black student enrollment. In 1986, he became the first black assistant to the Virginia Tech president before going on to become city manager of Richmond, Virginia.

"[Former Virginia Tech] President William Lavery made a commitment to address our lack of diversity," said Jamison, now the vice president for administration at the University of Texas at Dallas. "Prior to our aggressive efforts, there was very little to do in Blacksburg, [but] going from three to 14 black student organizations changed the culture on campus."

Today, the university continues to strive for diversification. In 1975, 275 students, or 1.4 percent of the student body, identified as black or African American. By the 2013-14 academic year, those figures had risen to 1,197 students, or 3.8 percent.