by Mason Adams

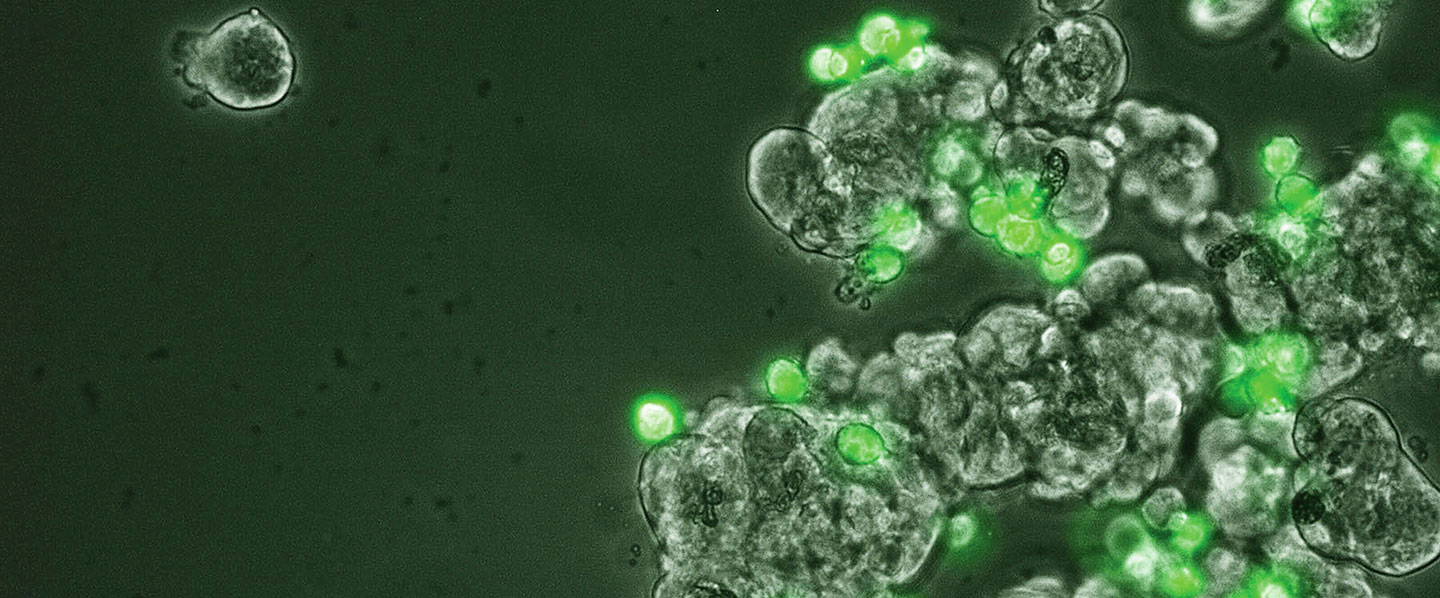

The header photo displays, in brilliant green, macrophages—a type of white blood cell—that are meant to eliminate microscopic invaders. In this case, though, ovarian cancer cells have redirected the function of the macrophages so that they protect the invaders, according to Associate Professor Eva Schmelz, who provided the image.

Cancer touches nearly everyone in some way.

As humans live longer, cancer seems to lurk in the shadows, ready to pounce when least expected. If it were a demon, cancer would be the "Legion" of the Gospel of Mark's fifth chapter, for the disease appears in many forms.

The complexity of understanding and fighting cancer may lead us toward such daunting images. Indeed, each cancer is unique unto itself, different both from other types of cancer and from how it progresses in individuals it afflicts. Some forms have been controlled and nearly eradicated; others continue to baffle scientists and kill within a matter of months.

"Each cancer is a world," said Carla Finkielstein, associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science (COS). "They all need different strategies and different approaches."

In the fight against cancer—an extensive war, waged on many fronts and dependent on an ever-shifting supply of resources—Virginia Tech faculty, students, and alumni fill the ranks.

The caregivers

For cancer patients, Angela Charlton '82 (right) develops therapeutic diets based on nutritious foods, while Mary Ward '80 (left) manages a cancer registry for Carilion Clinic. The women, employed in the Carilion health care system, posed at the Roanoke farmers market.

Experiencing cancer—through a friend or family member, or personally—often leads to a stay in the hospital and a range of interactions with doctors and nurses there.

At Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital, Mary Ward (biological sciences '80) and Angela Charlton (human nutrition and foods '82) are devoted to serving patients suffering from cancer and the side effects of such treatments as chemotherapy and radiation.

Ward started down her path of service when, to facilitate a career change by her husband, she attended nursing school to pursue a new job.

"The plan was I'd be a nurse a couple of years, and he could switch gears," Ward said. "Then I realized I loved what I was doing. I loved working with my patients. It was a ministry, not just a job. It was being with people. It was holding their hands. It was looking into their eyes."

For 14 years, Ward worked as a staff oncology nurse at the hospital. Chemotherapy and radiation require repeated treatment, extending the chances for interaction with the patients.

"You really build a trust relationship with them," Ward said. "As difficult as it is to be on the giving end as a caregiver, I often would tell people my patients gave me more than I gave them. Watching them deal with their illness and the courage and determination that they had was often inspirational, even with patients who were terminal. It would help me to remember my own mortality, to give me perspective on the fact we're not here forever."

In 2013, Ward moved into an administrative job managing Carilion Clinic's cancer registry, which plays an integral role in providing the hospital's decision-makers with ground-level data. The information compiled by Ward is incorporated into survivorship care plans, quality-improvement studies, prevention and screening programs, and more.

Charlton, with a background in nutrition, focuses on patient illness in clinical settings. At the Roanoke hospital, she said she is "intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually" engaged with cancer patients who are facing questions of life and death.

"You have to be able to be present in that reality, in situations where people are grappling with that," Charlton said. "You can't just rush in and rush out. You have to be available and listen to their stories. Sometimes you have to hear them repeatedly. People are grappling with a lot of important things."

"My patients gave me more than I gave them. Watching them deal with their illness and the courage and determination that they had was often inspirational." Mary Ward '80

To help cancer patients deal with disease symptoms or treatment side effects, Charlton plans therapeutic diets to deliver protein and calories when patients have upset stomachs and little desire to eat. Meals play an important social role in life, and disruption of that ritual can dramatically affect a patient's esteem and mood.

"Finding things that are meaningful, whether it's what type of diet approach or routine or rituals around food, gives [patients] some control and some sense of empowerment in how to move forward," Charlton said.

As long as cancer patients require hospitalization as part of their treatment, caregivers like Ward and Charlton are crucial. Thankfully, researchers at Virginia Tech and elsewhere are working on new, less-invasive treatments that may help minimize hospital stays.

The scientists

Eva Schmelz, associate professor of human nutrition, foods, and exercise in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, collaborated with P. Christopher Roberts, former associate professor of virology in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, to develop an animal ovarian cancer model aimed at discovering the initial changes that would signal the cancer's presence. Schmelz has also studied the role that natural and synthetic sphingolipid metabolites play in the prevention of cancer as an alternative to more conventional drugs, which often have toxic and debilitating side effects.

Rafael Davalos, professor at the Virginia Tech-Wake Forest University School of Biomedical Engineering and Sciences, develops biomedical devices to diagnose and treat cancer. One project involves isolating tumor-inducing cells circulating in the blood stream so that they can be identified before the cancer is otherwise detectable. Another has resulted in technology that uses applied electric fields to specifically target tumor cells while leaving healthy tissue unharmed.

Virginia Tech faculty members investigate not only potentially groundbreaking treatments, but also the biological mechanisms that help explain why and how cancer occurs. Often, their work begins with intellectual curiosity and a fascination with physiology, cellular biology, and more. In turn, their discoveries have enormous potential for real-world application. Published in scientific journals and textbooks, the findings contribute to the world's cancer knowledge and act as a foundation for future scientists. With colleagues from Tech and around the world, the researchers share information and collaborate. Associate Professor Rafael Davalos, for example, provides technical expertise and devices that often complement the work of others.

Daniela Cimini, College of Science associate professor of biological sciences, identifies and characterizes the cellular mechanisms that induce aneuploidy, a defect that results in an abnormal number of chromosomes and is known to be a main feature of cancer.

Carla Finkielstein, College of Science associate professor, studies how environmental factors influence cancer incidences by understanding how changes in circadian rhythms affect cell division and contribute to the development of breast cancer in women. Her research merges an understanding of cells at the molecular level with larger, community-based prevention strategies.

The adapters

While cancer research at the cellular level can feel only theoretical, veterinary medicine offers a bridge of sorts, providing foundational knowledge for those fighting cancer in animals and humans.

John Rossmeisl (M.S. veterinary medical science '03), associate professor of small animal clinical sciences in the vet med college, studies cancer in dogs whose tumors are closer in size and molecular and genetic heterogeneity to those in humans than are the tumors in rodents, which many researchers study.

"A mouse tumor may be 2 millimeters by 2 millimeters, but then you have to adapt it to humans, who may have tumors measuring 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters," Rossmeisl said.

Both Rossmeisl and Timothy Fan (biochemistry and nutrition '91, D.V.M. '95), an associate professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, are collaborators on human trials with cancer treatments that originated in dogs.

John Rossmeisl '03, associate professor of small animal clinical sciences in the vet med college, is a neurologist and brain surgeon who specializes in developing therapeutic approaches for gliomas, a fast-moving form of brain tumor.

Timothy Fan '91, '95 (right), an associate professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, studies canine osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer, and is now investigating a drug being tested in human clinical trials.

Fan is recognized for his work with canine osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer, and pain management for animals suffering from it. Like Rossmeisl, Fan's collaborators often partner with him to take treatments developed in rodents to the next level. Making the leap from discovery toward application, Fan is now investigating a drug being tested in human clinical trials in Chicago.

"It's very unusual for a small molecule or novel therapeutic approach that originates from a scientific investigator to move to a successful, new drug application and phase I clinical trial," Fan said. "Most agents making that path come from 'Big Pharma,' or large pharmaceutical corporations."

Similarly, Rossmeisl's work with Associate Professor Rafael Davalos on irreversible electroporation, a technology that uses electrical fields to precisely target tumors, has been commercially licensed, and their findings are being developed ahead of human clinical trials.

The distributor

Before the clinical trials, animal research, and cellular-level investigations, there is the matter of funding. As director of the American Cancer Society's (ACS) Preclinical and Translational Cancer Research program in the Extramural Research and Training Department, William Phelps (M.S. botany '80) coordinates committees of experts who weigh which grant applications to support.

At the American Cancer Society (ACS), William Phelps '80 coordinates committees of experts who determine how to allocate ACS funding to support the most-promising areas of cancer research. In 2014, ACS—the largest nonprofit, nongovernmental supporter of cancer research in the U.S.—spent $144 million on research.

"My job is to help make the best decisions to put money into the most-innovative and promising areas of cancer research," Phelps said.

Ultimately, only 10 percent of the applications receive ACS funding, but Phelps provides guidance to unselected applicants to help them win funding from other sources, such as the National Institutes of Health. Additionally, he plays a role in ACS fundraising, traveling around the country to share with donors how their money will be used.

Phelps' duties afford him a broad perspective on the fight against cancer. "Anybody engaged in a research enterprise has to understand that it is mostly an incremental industry. You're taking what someone has found and trying to incrementally learn something new. It's going to be fraught with failure, but that's the way you learn. One success comes out of 10 failures," Phelps said.

Still, those rare successes stack up to make progress. Since 1991, cancer mortality rates have fallen about 1 percent per year. That's not because of any one factor, Phelps said, but from many: a decrease in the number of people smoking, advances in medicine and treatment, and substantial progress in fighting particular types of cancers.

"Take childhood leukemia," Phelps said. "Ninety percent of kids less than four years old will be cured. That number didn't start out at 90 percent. It started much lower, but over the years, we have incrementally improved the survival and cure rates. It wasn't one thing, but the accumulation of thousands of studies that got us to a great success rate."

There is also rapid development in immune therapies for cancers like melanoma. "We got there because people have been unsuccessful with immune therapy for decades," Phelps said. "They'd try something, [it wouldn't] work. Try something else, going back and figuring out, 'Why did it fail?' That led to successes today."

The rally point

Video by J. Scott Parker | Visual and Broadcast Communications

Emily McCloud '15 and her mother, Ruth Intress, have lost three family members to cancer: Emily's father, aunt, and grandfather (Ruth's husband, sister, and father). McCloud was the director for Virginia Tech's spring 2015 Relay For Life event.

Research grants don't grow on trees, of course. Grassroots efforts such as Relay For Life—the top money-generating event for ACS—provide a financial foundation for groundbreaking research.

For six years in a row, Virginia Tech has hosted the world's largest, most-successful collegiate Relay for Life. Since 2009, Hokie students have raised more than half a million dollars each year. This year, the event attracted more than 8,000 participants on the way to exceeding $500,000 once again. Since Tech's relay efforts began in 2000, Virginia Tech has raised $4.8 million for cancer research.

"It takes at least $100,000 to fund an ACS grant," said Emily McCloud (mathematics '15), the 2015 event director who will return to campus in the fall as a graduate student. "Virginia Tech is proud to say we can fund five grants each year."

McCloud lost her father to cancer when she was 12. In the years since, she has lost her aunt and grandfather, too. She participates in Relay For Life in memory of her father and in honor of her mother, who in turn lost her husband, sister, and father.

"Life is short. It's a cheesy phrase you hear, but cancer is a crazy-scary disease, and it's incredible how hard you have to fight this," McCloud said. "It changed our lives. We moved, and I met new friends, and it was different growing up with just one parent. … The most motivating thing for me is that I have grown up without a father and don't want other kids to deal with that. That's what motivates me."

A personal commitment to the university motto, Ut Prosim (That I May Serve), further influenced McCloud. In her freshman year, she first learned about the relay from her residential advisor, and she volunteered to help with stage management.

"I remember standing under the tent, holding the scripts, [and] directing everyone," McCloud said. "I loved why I was there and loved being able to help out and make the night a great experience for other students. I knew then that Relay For Life was what I wanted to do with my college experience."

The manager

Ask scientists if cancer will be cured in the foreseeable future, and they're likely to hedge, saying that cancer someday will be more manageable, more of a chronic disease than a lethal one.

Making cancer manageable is the goal of Karen Roberto, a University Distinguished Professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences' human development department who since 1996 has served as director of the Center for Gerontology.

Roberto's research focuses on rural Appalachia, where older adults carry a disproportionate share of the U.S. cancer burden and face environmental factors that present major challenges to treatment and survival. "Understanding differential cancer burden as a result of individual and life-course circumstances is necessary for the development and implementation of best practices to provide optimal care and support for all cancer survivors," she said.

As part of the Appalachian Cancer Network, Roberto and the Center for Gerontology work with churches in Giles County and Galax, Virginia, to offer a curriculum that includes faith, exercise, diet, and regular cancer screenings as preventative measures. The interactions have generated data on how health disparities are amplified by rural economics, perceptions, and age.

Those ages 65 and above comprise 13 percent of the U.S. population, but account for 54 percent of all new cancer cases, Roberto said, adding that approximately 60 percent of survivors are older adults. "Our view of cancer has changed from a death sentence to more of a chronic illness," she said.

As a result, the number of older cancer survivors is likely to continue to increase. Said Roberto, "It is important for medical and public health professionals, as well as family caregivers, to be knowledgeable of issues survivors may face, especially the long-term effects of treatment on their physical and psychosocial well-being."

Higher survival rates are a good problem to have, of course. But for those who've won their battles, and for their families and doctors, the extended lifetimes trigger a need to further explore and improve caregiving methods.

If each cancer is a world, as Finkielstein said, the Virginia Tech community is fully engaged in winning each battle—and the broader war—against cancer in all its forms.