by Mason Adams

For some, the term "hacking" may bring to mind the image of shadowy figures stealing data or planting viruses. But among programmers and innovators, the term has come to represent the concept of tinkering and repurposing objects to make them work better. As coding assumes a more central role in the digital world around us, Virginia Tech exists both as a destination for talented hackers and as a guiding force to harness that ability for the greater good.

On a chilly, late-winter weekend, Torgersen Hall was overrun by students — and their energy drinks, snack wrappers, laptops — for two marathon days of rapid-fire in the annual VTHacks competition.

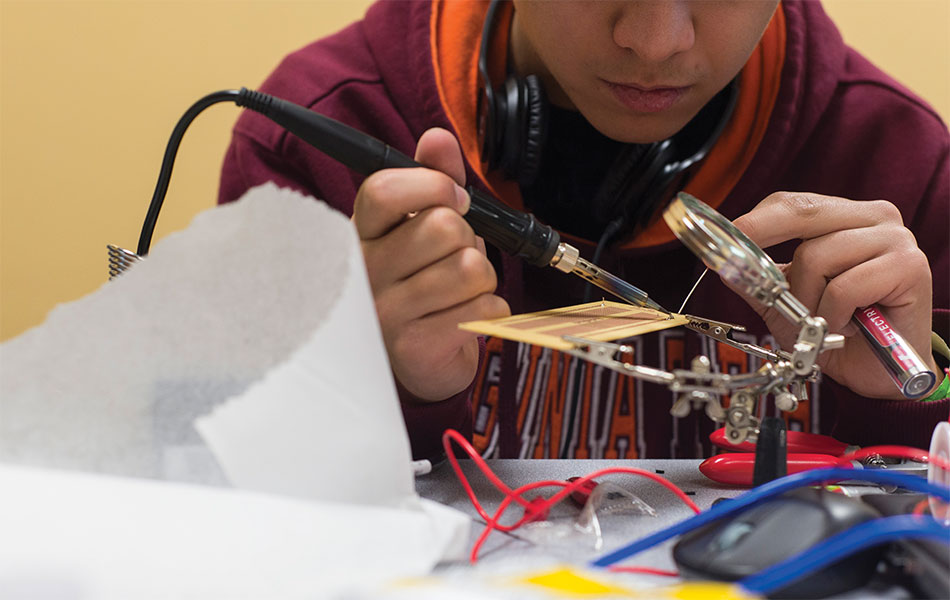

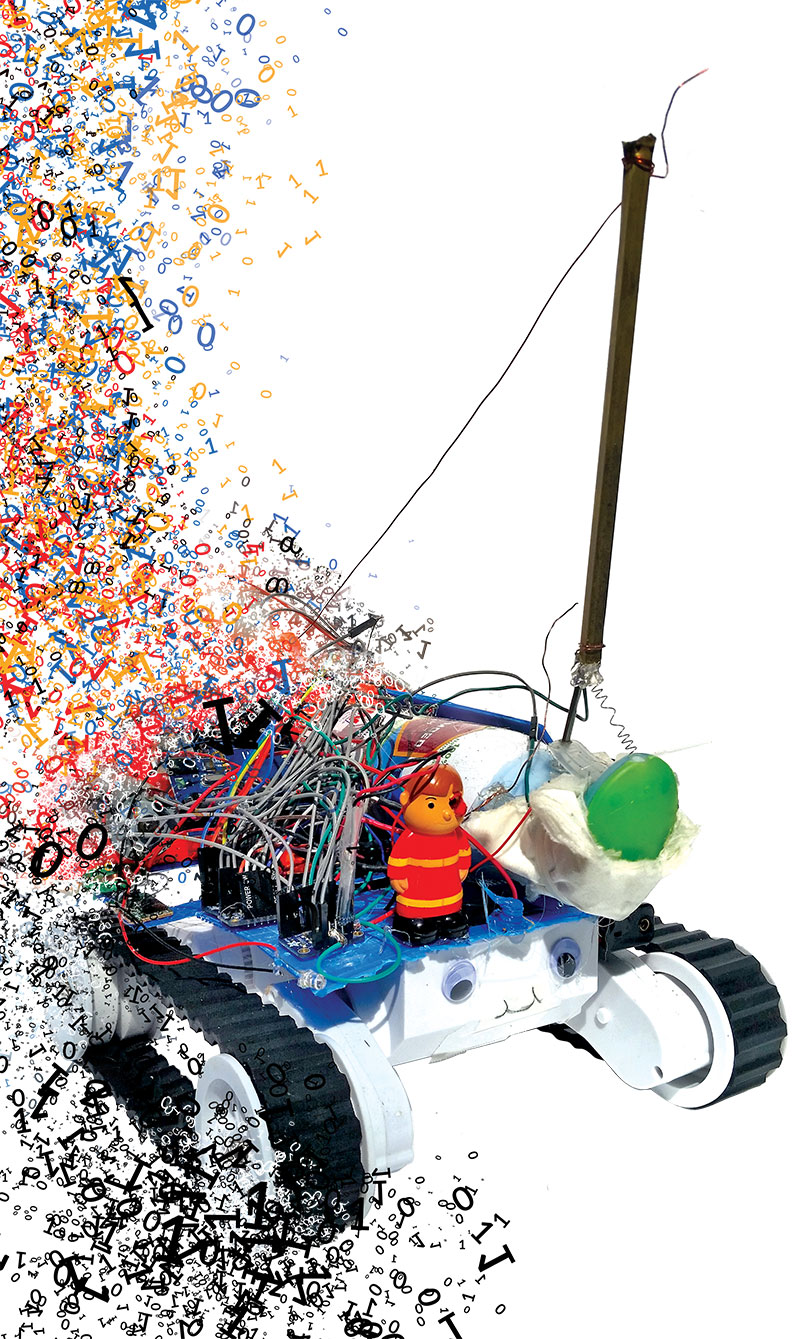

A pair of virtual-reality goggles hung from Scott Ziv's 3-D printer as he and his two teammates huddled over the frame of a radio-controlled car, stripping its parts and reprogramming its electronic innards.

Ziv, a rising senior and mechanical engineering major, conferred with Matthew Ritzinger and Steven Roberts — his "code monkeys," as Ziv called them — as they game-planned how best to transform the vehicle into a Febreze-spraying robot. A third coder, Jack Beach, a rising junior majoring in computer engineering like Ritzinger and Roberts, assisted.

The Fabreze-bot, part robot and

part air freshener, was built at VTHacks.

The next 36 hours rushed by as they wrote code for the robot's software, 3-D-printed a gearbox, added Bluetooth capacity, and wired the motor. In the waning hours before Sunday's 9 a.m. deadline, the team cooked pizza on the 3-D printer's heated bed before rushing to Walmart for a toy truck with a siren, so that the Febreze-bot could sound off whenever the fragrant spray was activated.

What's the point of a Febreze-bot? Well, in and of itself, not much. The team-based envisioning, building, and trouble-shooting, on the other hand, is invaluable.

To Ziv, the process is emblematic of a larger truth that a former art teacher once shared with him: "Life and art are about problem-solving." As Ziv said afterward, the machine worked "flawlessly, in the worst possible way." In other words, they're still learning.

Increasingly applied to diverse fields, hackathons have a unique way of generating teamwork, as participants of varying backgrounds, skill levels, and expertise rush to complete a project by a deadline. In a sense, a hackathon is something of a small-scale model for what Virginia Tech hopes to accomplish with its Destination Areas, which encourage interdisciplinary problem-solving.

Cool collaboration

Both for his creativity and his striking blond afro, Jordan White stood out among the students who organized VTHacks. White, a rising senior and former president of the Virginia Tech Entrepreneur Club, first attended a hackathon at Yale University during his freshman year at Tech. "The amount you could learn and create in one weekend was really cool and exhilarating," White said.

The Entrepreneur Club hosts its own spin on a hackathon called "Built with:____." Attendees write down five skills on sticky notes, with their contact information on the back, and post them on a large board — essentially providing a list of resources available on demand. Students then collaborate on ideas and projects, with many individuals floating between groups as their skills are needed. The February event drew 200 students representing 47 different majors.

White, who is majoring in computer science with a minor in industrial design, co-founded a design and development company with fellow computer science major Ojas Mhetar and another friend after a 2014 hackathon at which the team created a full-fledged iPad app to teach college-aged bachelors how to cook 15 basic meals.

The hackathon trend reflects the growing presence of computers in our lives. According to a 2015 report published by Ericsson, a Swedish technology firm that supports the telecommunications industry, the number of smartphone subscriptions will grow from 2.6 billion today to 6.1 billion by 2020. Additionally, computer technology is increasingly present in everyday objects — the so-called Internet of Things, or IoT for short.

Destination for excellence

Five Destination Areas — sites of interdisciplinary collaboration where experts are positioned to address the full complexities of broad, societal-scale problems — will launch at Virginia Tech in the fall semester.

Learn more about the five areas→

• Adaptive Brain and Behavior

• Intelligent Infrastructure

• Global Systems Science

• Data Analytics and Decision Sciences

• Integrated Security

Destination for excellence

Five Destination Areas — sites of interdisciplinary collaboration where experts are positioned to address the full complexities of broad, societal-scale problems — will launch at Virginia Tech in the fall semester.

Learn more about the five areas→

• Adaptive Brain and Behavior

• Intelligent Infrastructure

• Global Systems Science

• Data Analytics and Decision Sciences

• Integrated Security

This exponential digitization offers a world of opportunities leveraging large data sets to improve human lives — and also opens doors for the unethical or downright malevolent use of data.

Two of Virginia Tech's new Destination Areas, Data and Decision Sciences and Integrated Security, aim to unleash the university's most talented innovators on problems in those spheres. The former involves the computer-enabled collection and analysis of datasets, which will boost living quality by providing otherwise invisible insights into our world. The latter is closely related, protecting that data and other assets while balancing privacy concerns.

Hacking for health

In April, the Center for Business Intelligence and Analytics (CBIA) in the Pamplin College of Business partnered with AT&T to sponsor the Mobile Apps for Global Good in Healthcare hackathon, designed to lead to smartphone applications that improve health, reduce costs, and enhance the patient's experience.

In a mere 24 hours, the winning team — Jonathan Briganti, a rising senior majoring in neuroscience; Brian Elliott, a double major in electrical engineering and computer engineering who will graduate in December; and Madeline Yaskowski, a rising sophomore majoring in public relations — built an app to track mental health and detect early warning signs of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Along with a $2,500 prize, the team won the attention of healthcare provider Carilion Clinic, which has continued to work with Briganti and Elliott to further develop the app.

That transcendent outcome is the type of result that CBIA executive director Linda Oldham wants to encourage. Oldham is guiding a new one-year master's degree program that confers a master of science in business administration with a concentration in business analytics. The 30-credit-hour program is split evenly between business and analytics cores, with a capstone project whose structure somewhat resembles an extended, narrowly focused hackathon.

About 20 students are signed up this summer for the pilot program, whose sponsors include IBM, Altria, HP Enterprise Services, Beyer Automotive, and Carilion Clinic.

Companies will challenge the student cohort with a range of data and problems, and the students will form interdisciplinary teams to bid on the projects. The students will meet weekly with their corporate sponsors, while learning from Oldham how to build a business case that can yield a high return for the sponsor.

Big forecasts

Besides coding and hacking, Virginia Tech teams have also competed well in contests to analyze large datasets.

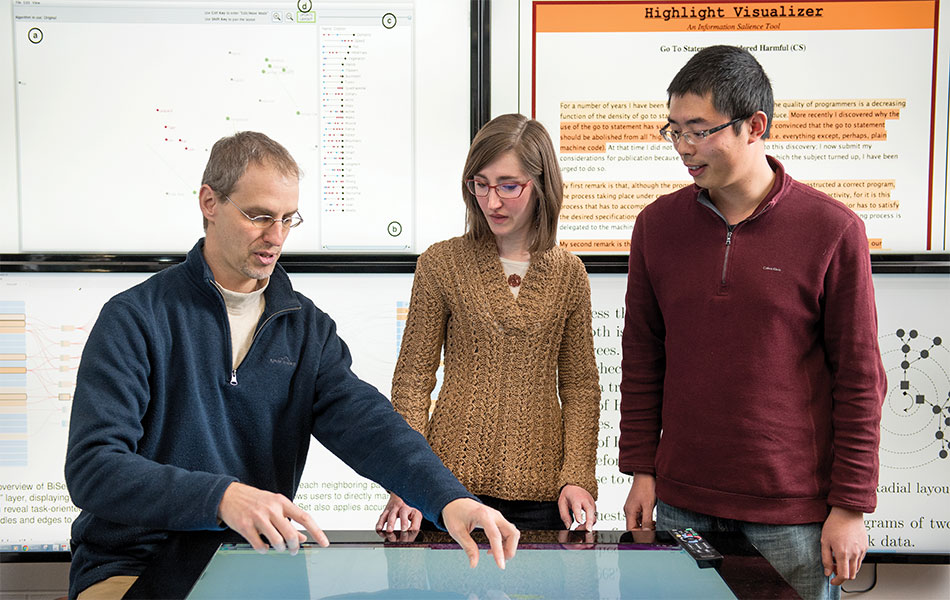

Five years ago, Naren Ramakrishnan, the Thomas L. Phillips Professor of Engineering, and other faculty members from the departments of Computer Science, Statistics, Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Mathematics, founded the Discovery Analytics Center (DAC) as a home for collaborative research. Along the way, they created new courses and a curriculum that now trains students in big data techniques.

The center's students often win data-science competitions. One 2013 challenge involved a dataset of user-submitted reviews from online review company Yelp, which asked teams to organize the information in novel ways. The Tech team, one of four winning teams, created a program that visualizes reviews such that semantically related words are spaced close to one another, thus improving users' understanding of a large number of reviews.

Another DAC-based team developed EMBERS (early model-based event recognition using surrogates) for Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, a federal agency known as IARPA. Declared the winner of an IARPA forecasting tournament, EMBERS uses algorithms analyze a continual feed of open-source data to forecast significant societal events such as protests and disease outbreaks around the globe.

"Whatever degree you pursue at Virginia Tech, it is important to have some level of data literacy, to understand how data undergirds your discipline, and to use the methods of data science to complement your disciplinary work," Ramakrishnan said. "If you have this data-science concentration, you add a lot of value to your education and immediately open yourself to a lot of possibilities."

Virginia Tech Magazine [winter 2014-15] story about EMBERS and DAC

Bridge-builders

In the university's National Capital Region, the Ted and Karyn Hume Center for National Security and Technology is home to another interdisciplinary program aimed at data and security. Encompassing the technical, policy, and regulatory aspects of cybersecurity, the CyberLeaders2020 certificate program begins this fall thanks to a $500,000 grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, a California-based philanthropic organization.

Capitally speaking

With locations in Alexandria, Arlington, Fairfax, Falls Church, Leesburg, Manassas, and Middleburg, Virginia Tech's National Capital Region (NCR) links academia, industry, and government in entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic development. The NCR presence includes seven colleges and more than 45 graduate degree and certificate programs, including two executive master's programs in business administration and natural resources. The faculty roster of more than 85 active researchers accounts for more than $15 million in research expenditures focused on four main areas: national security, resiliency, energy and sustainability, and health and life sciences. Cutting through these areas are cross-disciplinary capabilities in policy and data analytics that help solve national and regional problems.

Capitally speaking

With locations in Alexandria, Arlington, Fairfax, Falls Church, Leesburg, Manassas, and Middleburg, Virginia Tech's National Capital Region (NCR) links academia, industry, and government in entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic development. The NCR presence includes seven colleges and more than 45 graduate degree and certificate programs, including two executive master's programs in business administration and natural resources. The faculty roster of more than 85 active researchers accounts for more than $15 million in research expenditures focused on four main areas: national security, resiliency, energy and sustainability, and health and life sciences. Cutting through these areas are cross-disciplinary capabilities in policy and data analytics that help solve national and regional problems.

"We need policy people who understand the technology, and we need technology people who understand the legal, ethical, and policy implications," said Janine Hiller, the Richard E. Sorensen Professor of Finance and a longtime cybersecurity scholar who is teaching part of the CyberLeaders curriculum. "The technology won't lead us to places that we want to be as a society if we don't talk to each other. We need to create bridges."

Since its founding in 2010, the Hume Center has been working to create those bridges. A large part of the center's efforts — in support of military organizations and the defense contracting community — is cybersecurity, said center director Charles Clancy.

Students at the center are often able to obtain security clearances and work on classified projects while still in school, Clancy said. That clearance, attractive to prospective employers, adds an estimated $10,000 or more to a graduate's starting salary, he said.

Thus Tech graduates are well-positioned in the rapidly growing cybersecurity market, which is projected to balloon from $75 billion in 2015 to $170 billion by 2020. A Stanford University study found that nearly 250,000 federal cybersecurity jobs are unfilled, and the number of job postings grew 74 percent from 2010 to 2015.

Data protection

A steadily growing number of Tech alumni have found homes in the cybersecurity sector, especially in and around Washington, D.C.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulates the interstate transmission of energy, such as electricity, natural gas, and oil. Behind the scenes is Mittal Desai (business information technology '06), FERC's chief information security officer and chief privacy officer.

"The data [that FERC] uses on a daily basis can make very profound impacts in how we regulate energy for the United States," Desai said. "The data is very sensitive in nature. The work I do is to protect our mission-critical systems and data from being compromised."

His unit supports FERC departments against cyberattacks. "As technology evolves, a lot of these criminal acts are getting more sophisticated at an alarming rate," Desai said. "We can't be stagnant. There's something new coming down the line all the time, whether it's a new malicious actor or some new form of cyberattack. For a lot of individuals in this field, that's what keeps them up at night."

Desai estimated that he splits his time, half and half, between technical work and other tasks that draw on his interdisciplinary background. His Pamplin education grounded him in business basics — accounting, finance, information technology, and marketing — before exposing him to technological material, with capstone classes on networking and database design and development.

Besides the technical side of the job, Desai communicates with colleagues, manages budgets, oversees cybersecurity marketing initiatives, and more. "Interdisciplinary studies are important because you develop those building blocks. Those, coupled with technical knowledge, make you well-rounded in the field," he said.

Joshua Higgins (communication, political science '14) writes for Inside Cybersecurity, a daily industry publication.

"Within my first week of starting, I realized cybersecurity is not just an IT issue. It's an economic issue," Higgins said. "Based on that perspective, I think it's important to have IT people and business executives and policy people working together, combining those different aspects together to create the environment you need to combat the hackers that are always 10 steps ahead of the good guys."

Hacking problems

Outside of technical fields, a knack for coding and cybersecurity is becoming more and more important. A graduate in the humanities may not need to know how to build an app from scratch, but an understanding of the basics, including data security, will allow for a fuller understanding of the increasingly digitized world.

At VTHacks in Torgersen Hall, student teams tinkered away. One group broke down the steps for an app on tracking health metrics. Another worked to transform photos into artwork modeled after the style of various painters. Another app was meant to motivate users to exercise.

Jaketa Linzy, who graduated in May with a mathematics degree, dove into a tutorial for Javascript, a coding language. Although she had just one coding class under her belt, she and a friend majoring in sociology were building a website from scratch.

"I tried to do as much as possible last night, but I made very little progress," Linzy said early in the weekend. But she's no longer intimidated by coding. "I am learning a lot, and that's ultimately the purpose of doing this."