edited by Su Clauson-Wicker

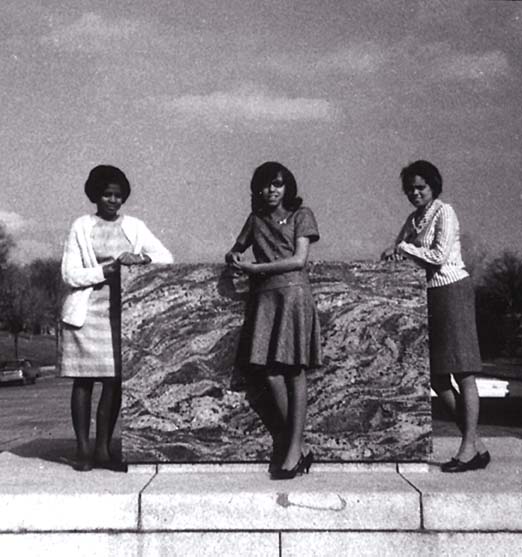

The first black women students entered Virginia Tech in the fall of 1966: transfer student Linda Adams, Jacqueline Butler, Linda Edmonds, Fredi Hairston, Marguerite Harper, and Chiquita Hudson. They were a minority within a minority -- six black females in a sea of about 9,500 white men, 500 white women, and 20 black men.

It was rough; everyone seemed to be watching. At the end of the first year, Hudson had died of lupus; in another year, Adams had graduated and Hairston had married a white classmate and left school. Harper, Butler, and Edmonds share their memories of moving past barriers to become, with Adams, Tech's first black alumnae.

"I had never heard of Virginia Tech. It was not in my realm," Harper says. She was planning to attend Virginia State, like all her relatives. But when a Virginia Tech recruiter visited her Norfolk high school, earnest about getting black students on campus, she took home an application.

"My father decided that I would apply. 'Go and teach them about black people; learn about how to live with white people,' he said."

She was accepted and received a full scholarship -- a Rockefeller Scholarship for culturally disadvantaged students. "'Take the money and go,' my father said. 'You can teach them who is culturally deprived later.'"

Harper was warned by a high-school counselor that she would do poorly because her education was inferior to the white students', but that admonition only gave her more resolve to succeed. She discovered she was in the first class of black women only when her mother read it in Jet magazine in October 1966.

"The other students were basically kind of indifferent to us. People who lived beside you tended to be more friendly. But, come the weekend, there was this little wall that separated us. They went their way, and you went your way," she says.

"Most of the racism I experienced was subtle. But not always. I didn't realize how big the flag and 'Dixie' were here until my first football game. The cheerleaders would run onto the field with this huge rebel flag, and then the Highty Tighties would come out playing 'Dixie.' You were expected to stand as if it were the national anthem.

"There's no way I was standing for 'Dixie.' I remember someone punching me in the back and telling me to stand. I looked at him, and I said, 'You best not put your hands on me again.'"

Harper noticed that the Confederate flag came down when important African-Americans, such as Erroll Garner, came to visit. Obviously they felt that this would be insulting to him. "Why don't they think it's insulting to me?" she asked. She was elected to the student senate her sophomore year and made a successful resolution to get rid of Dixie and the flag.

"We received hate mail and ugly telephone calls. My roommate at the time, Natalia Herdami, was white, and so she got threatening phone calls about living with me ... There was a demonstration. This campus was covered in Confederate flags hanging out of the windows. 'Dixie' was blasting out of the doors. I had a Nina Simone protest-song record that I used to play on Sundays for parents of the girls who wouldn't speak to me. I'd open my door and have my 'Mississippi, God Damn' playing out there until my roommate would say, 'Come on, now; give them a break.' That was my way of dealing with it.

"I remember having to have that facade at that point. When I first came here, I was a sweet child. By the time I left, I was Umoja black power. I guess I tried to become intimidating as a defense mechanism to survive."

When the Supreme Court struck down miscegenation laws in 1967, the university human relations council that Harper attended decided to test the ruling on campus. Harper and a white classmate set up a "date" one reunion weekend.

"When fellows came to see a girl, they'd have to ask the dorm mother to call her to come downstairs. There was a substitute there, and she asked my date, 'Do you know that she's a colored girl? I'm not going to call her for you.' And so he had to get a another girl to let me know he was there.

"We sat on the faculty/alumni side of the concert. We wanted the old people to see us. Sure enough, the next day the dean of women called me in and let me know that she had seen me and that I looked so nice and what have you. She said one lady had asked, 'Did you see that colored girl and that white boy last night? What are you gonna do about it?' And the dean told her, 'What do you mean, what am I gonna do about it? Here at Virginia Tech, students can date whomever they please.' She knew what I was doing, obviously. That was to let me know: 'Back off. I'm not gonna bother you folks anymore.'"

After graduation, Harper taught in Norfolk City schools during the year when busing began and schools were integrated. She is still teaching school in Cary, N.C., where she lives with her husband and two children.

"I don't look back with regret," she says, "I wanted to make things happen. This was a grand place for me to do it. We were the first. They didn't know what to do with us, apparently. We had to be paired together, and I roomed with a white girl the next year because, hey, we're not going to do it the way you want us to do it. I felt somewhat like a pioneer, and I think that molded how I was going to be for the rest of my life."

Hairston came to Tech from Roanoke and roomed with Linda Edmonds in Hillcrest during their freshman year. Both Hairston and Edmonds joined the University Choir. Hairston was on the news staff of the student newspaper, Virginia Tech. She and Larry Billion (psychology '69) wrote "Back Talk," a column that dealt with controversial issues and presented both sides of the topics.

In the fall of 1967, they did a column on miscegenation, which concluded with "The children of an interracial marriage are the only victims of miscegenation. This is solely because of the hypocrisy and cruelty of man. The day is coming when people will realize that the ostracism of children because of their heritage is meaningless."

Hairston married Tech junior Robert Clegg, a white civil rights activist, at the end of her sophomore year, and they both left Virginia Tech.

Jackie Butler graduated at the top of her class in Lancaster County, Va., and came to Tech on a $4,000 Rockefeller scholarship. Before Tech, she had little contact with whites and no expectations about what she would encounter.

"The girls in the dorm were fine -- we were all friends. I never had any problems in the dorm, but in the cafeteria ... sometimes when we sat at a table, the students would get up and move to another table. That was only the first year. The students, once they got to know you, were fine. Once you had interacted with them, race wasn't important.

"The first year was the hardest. You would feel like everyone was staring at you. And I remember sometimes walking across the Drillfield when it was cold, and I would think that if I fainted here, no one would care. I would wonder if anyone would stop or if they would just keep going."

Butler still communicates with some of her white friends, including a special friend who's a missionary in Uganda. She had white roommates her last two years of school and spent her last semester in Germany living with a German family. She married Eli Blackwell (mechanical engineering '70) the fall after she graduated. (She graduated in three years.) Butler held training positions at the Virginia Employment Commission before their first child was born. Since then, she's been active in volunteer work, for the last six year as director of a volunteer program for her daughters' high school in Portsmouth, Va. Both her daughters, Lori and Stacy, are attending Tech.

Chiquita Hudson, from Hampton, had a single room because she had lupus and didn't want to disturb her roommate when she was ill. When the parents of the white roommate assigned to Linda Adams, a transfer student from Clifton Forge, refused to have their daughter room with Adams, Hudson moved in with Adams. Hudson died of lupus the summer after her freshman year.

Linda Edmonds graduated with top grades in Halifax County, Va., and came to Virginia Tech to major in clothing and textiles. She had visited campus in high school, thought of it as "a little fairyland, with buildings like castles," but had no notion of going to a white institution until that visit. The offer of a full scholarship to Virginia Tech from the Rockefeller Foundation also affected her decision.

"I was the only black student in my high school going to a white university then. The tension was building all summer. I started to really get afraid that I couldn't make it. Not so much that I didn't think that I had it, this was a totally different environment."

Edmonds says she and Hairston, her roommate, mixed right in at Hillcrest. "We did whatever the other girls did. There were pajama parties. We'd go; they might not have wanted us to, but we were there. We never considered ourselves uninvited."

"Our dorm mother, Mrs. Reynolds, was really sweet and southern and very hospitable to us. Some of the girls' parents' eyes got as big as saucers when they saw us. Sometimes when the parents would visit, they would ask us, 'Where do I get paper towels?' They thought Fredi and I were the hired help."

Edmonds tried to develop a relationship with a white student from her hometown. "I used to have to make her talk. I was determined, but not aggressive. She didn't want to talk to me, but as the years went by, she would talk more. She was always judging whether she should do it or not."

Edmond's biggest support came from a few staff and faculty members. "The black staff that cooked for Hillcrest treated Fredi and me just like queens. You could just see the pride in their faces. They would do little things, such as saving our favorites foods for us. Sometimes I'd see them outside the dorm, and they would say, 'We're proud of you. Just get your lessons, and don't let these folks bother you. We know it's hard, but you guys are the first!'"

Laura Jean Harper, dean of the College of Home Economics, was Edmond's true mentor. "Dean Harper hired me as her undergraduate teaching assistant. That woman continued to groom me, but I didn't even know it was happening. She would do things like this: she would say, 'Linda, take this report over to the president's office.' I used to wonder why. She was giving me exposure. I still talk to the former president (T. Marshall Hahn). He has been a mentor to me as well throughout the years. Dean Harper gave me that connection.

"She was a very abrupt, busy, busy person. She wasn't fake. If she didn't like something, you knew it. I thrived with her kind of guidance and the responsibility she gave me. I think she sent the message to the other faculty not to give me anything, but to be fair.

"I don't know if I would be sitting here today with a Ph.D. if it hadn't been for Dean Harper encouraging me. I'm first generation college. I decided to get a master's. She went to Michigan State, and I went there. Then I came back to Tech and got a Ph.D. in business in 1979."

Once she stepped out of the home economics building, Edmonds felt like a shadow. "Sometimes I saw racism on campus, but it was done subtly. Then there was some that just hit you dead in the face.

"A graduate teaching assistant taught the chemistry lab -- he would always just glare at me. He was red and fat and swollen, he reminded me of the term 'redneck.' One day a bottle of acid solution got knocked off the counter onto my legs. It completely ate the hose off my legs. I just froze. My lab partner froze. The guy behind us took some water and started pouring it on my legs to wash this solution off. The teacher came over and said, in a rough voice, 'You be more careful next time,' and walked away. Never looked to see if I had been injured. That little boy -- he couldn't have been any more than 18 either -- said to me, 'Linda, I think you need to go to the bathroom and take those off.'

"I walked out, and I started to shake. Dr. Furch, the chemistry professor, came down the hall and asked me what was wrong. When I told him, he got down on his knees to look at my legs -- not in a sexual or familiar way, but concerned. 'Miss Edmonds,' he said, 'you leave the lab immediately. Go take a hot bath, and if you feel any sort of stinging, go to the infirmary right away.' He reassured me that it was a weak solution and shouldn't bother me."

Edmonds said the lab instructor gave her a B rather than an A in the lab because she missed that class.

"If I could thank two people that I never did thank properly, it would be Dr. Furch and that little boy who washed my legs off. Dr. Furch only had one hand. If I could, I would grow him another hand. He seemed to care; a lot of the teachers didn't. I was there, and I did well, but they didn't give a damn one way or the other."

Edmonds made the dean's list, but felt driven to achieve. "I regret going through that period feeling I couldn't have a bad day. It was tough. I wonder if part of the reason the black students haven't really kept in contact is that we were so busy just trying to hold on then that when it was over, it was like a breath of air. We just went our separate ways.

"In some respects, Tech made me feel like a stepchild. It's my school and, even though we participated in everything, nobody cared that we did or didn't. I was lucky in that I had Dean Harper, but others didn't."

Edmonds, now Linda Turner, lives with her husband and son in Massachusetts, where she is assistant vice president of marketing at Dean College.

Thirty years later, 495 black women are enrolled at Virginia Tech. Tech's total black student enrollment is 1,064, or about 4.3 percent of the university's total. Public administration doctoral candidate Elaine Carter, who initiated the Black Women's History Project at the Virginia Tech Women's Center, says some black students on campus report feeling defensive, lonely, and marginalized. "The risk (to engage) is usually taken by the black student," she says. "Racism hasn't completely disappeared, but you find few willing to talk about it."

The university, however, has established programs to increase dialogue and awareness, including a multicultural awareness program led by student peer educators, a Black Cultural Center, and an orientation video dealing with racial issues.

This article was based on interviews by Elaine Carter and University Archivist Tamara Kennelly, located at scholar2.lib.vt.edu/spec/bwhp/bwhproj

Back to Features

Home | News | Features | Research | Philanthropy | President's Message | Athletics | Alumni | Classnotes | Editor's Page