|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An incredible number of National Science Foundation (NSF) Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Awards have gone to Virginia Tech faculty members, especially during the past two or three years. A CAREER Award isn't just a feather in the cap--a highlight on a vita--for an up-and-coming professor. The highly sought-after grants can launch a researcher's career, giving him or her the monetary means--$400,000 or more--to stock an academic toolbox for a long time, in the words of one winner.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia Tech's approximately 70 CAREER Award winners often secure additional research grants and attract other types of recognition after they receive the prestigious CAREER Award. For example, Marc Edwards, from civil and environmental engineering, has since won the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship and garnered national headlines for exposing America's deteriorating water infrastructure. Dennis Hong, from mechanical engineering, recently was named among the Popular Science "Brilliant 10 for 2009" and has been featured in top stories by The Washington Post and CBS News after leading a student team in rigging a dirt buggy so that it can be driven by the blind.

However, not every CAREER award winner captures zinger headlines. Most are working on projects that the public doesn't know about but soon will rely on just the same.

LEARNING NATURE, NATURALLY

Taranjit Kaur is breaking new ground in studying the habitat life of chimpanzees. In the 2003 abstract of her $752,320 CAREER grant, Kaur, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences and pathobiology in the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, said that an understanding of natural wild habitats--rhythms, cycles, dangers, and magic--cannot be recreated in a sterile laboratory. Her solution? Take a high-tech lab to the wilds of Tanzania's Mahale Mountains National Park. This successful effort is essential to her Bush-to-Base Bioinformatics program.

Kaur lived in the Tanzanian wild habitat of chimpanzees, along with her fellow researcher/husband and young daughter, for the better part of a year. There, she began studying how humans come in contact with chimpanzees and how viruses--respiratory colds for instance--can spread from human to ape. These animals have no immunity to human illnesses and could die.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taranjit Kaur used her CAREER award grant to begin studying the transfer of viruses from humans to apes. |

|

|

|

The research required high-tech tools and a safe enclosure in which to work, eat, and sleep. Using the CAREER grant, Kaur developed the Portable Laboratory on Uncommon Ground (PLUG) with faculty members and students in the College of Architecture and Urban Studies. The result was a compact futuristic tent lab built of lightweight aluminum-skinned panels, high-tension fiberglass rods, and fabric and powered by solar panels. Sleeping quarters are located above the work area. Its carbon footprint is negligible.Kaur says her time in Tanzania was magical, mystical, and dangerous. "You adjust. You have what you have, and that's it," she says, adding that no call for 911 can help with an emergency or a bout of malaria. She and her family readjusted to "the natural rhythm of the earth, where your day begins at sunup and ends at sundown."

Kaur is keen on the flow of nature in her teaching as well, eschewing the vertical god-disciple approach of the classroom for a horizontal approach in which she passes on information to her college charges, who in turn teach local elementary school students, who in turn teach their own classmates. "The idea is that once you learn something you're not done with it," Kaur says. "There's a bigger picture out there, and they are part of it and have a responsibility."

The Pennsylvania native is a first-generation college graduate, having chased bats from trees for fun as a child and worked in large animal research clinics before she was old enough to drive. What the second generation of college students will accomplish, one wonders.

PROTECTING SATELLITES FROM THE HARSHNESS OF SPACE

Launching a satellite into space isn't a done deal. It's more akin to tossing a featherweight boxer into the ring between Jake LaMotta and Sugar Ray Robinson. Once the satellite is in low Earth orbit (LEO), roughly an altitude of 100 to 400 miles, it spins around our planet at an astonishing 18,000 miles per hour. That amounts to 15 days and nights--vast changes in temperature from facing the sun to being on the "dark side" of the Earth--in a single 24-hour period. The quick, harsh temperature changes wreak havoc on a satellite's electronics. And that doesn't factor in the energetic solar radiation, which cannot be protected by the lower-lying ozone layer, or the high-energy collisions with the oxidizing natural species of LEO.

These harmful agents pummel a spacecraft by pricking, chipping, tearing, and eroding its exterior, protective surfaces. Diego Troya, an associate professor in the College of Science's chemistry department, is seeking ways that hold off the inevitable damage and thereby extend the life of satellites and other spacecraft, such as the International Space Station or the Hubble Telescope. Doing so can save untold millions of dollars in replacement craft or mid-space repair jobs. Troya is a theoretical chemist who creates computer models that provide microscopic-level details of a spacecraft's astonishingly fast journey around the Earth and the hazards it endures. His ongoing $550,000 CAREER grant is dedicated to developing computational technology that will help crack the mystery of the damage to the polymer surfaces coating spacecraft.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

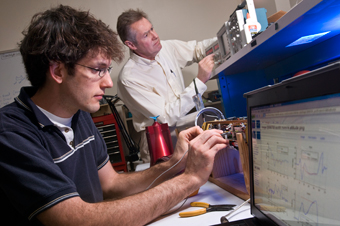

Diego Troya (left) calls his CAREER grant "huge" in developing a "robust toolbox." At right, Troya (center) helps William Alexander (left) and Joshua Layfield set up simulations for their satellite-protection research. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"It was huge," Troya says of winning a CAREER grant in 2006. "It gives you the necessary peace of mind to carefully develop a robust toolbox that you and other people can use to study complex problems." He since has received additional funding from the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the Research Corporation for Science Advancement to continue his work. Diego works with two assistants, Joshua Layfield, a fourth-year graduate student, and William Alexander, a postdoctoral associate. "I train them to write computer codes, set up simulations, and analyze them, but it's their work that determines the success of our enterprise," Troya says.

Since Russia's Sputnik 1 shocked the world in 1957, satellites have undergone massive changes in protection and design to lengthen their endurance and capabilities. But the task is far from complete. Work on improving the lifetime of satellites and spacecraft will continue as long as humans reach for space, and Troya will be there to help see that happen.

BUILDING AUTONOMOUS CRAFT FOR SKY AND WATER

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dan Stilwell (left) supervises the work of graduate student Brian McCarter on autonomous underwater vehicles. |

|

|

|

Unmanned boats, submersibles, and aircraft have been the stuff of sci-fi lore for decades, with fiction becoming fact only during the past several years. Consider, for example, the unmanned aerial drones regularly carrying out U.S. military reconnaissance and attack missions in Afghanistan. The future of autonomous craft on sea, air, and land is wide open for both military and scientific purposes, and two of the field's leaders, Dan Stilwell and Craig Woolsey, are members of the College of Engineering faculty.Now an associate professor in the Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Stilwell in 2003 received a $400,000 CAREER grant and a $300,000 Young Investigator Program award from the U.S. Office of Naval Research to develop groups of low-cost miniature autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that cooperate underwater. Woolsey, of the aerospace and ocean engineering department, won the same awards in 2002. His research focused on internal shape control for ocean and atmospheric vehicles and low velocity attitude control for underwater vehicles using internal actuators.

Both men spearhead research labs dedicated to building unmanned craft. Stilwell's group is the Autonomous Systems and Control Laboratory, while Woolsey runs the Nonlinear Systems Laboratory. Both researchers led the development of the Virginia Center for Autonomous Systems, a college-level organization that seeks to support and promote autonomous vehicle research at Virginia Tech. At the center, dozens of faculty members and graduate students contribute to a broad field of autonomous vehicle systems for air, ground, and maritime use.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAREER Award winner Craig Woolsey works with students Laszlo Techy, Mark Monola, and Eddie Hale (top to bottom) on improving small robotic aircraft. |

|

|

|

Among Stilwell's Department of Defense-funded projects are small torpedo-shaped submersibles, developed with Wayne Neu, associate professor of aerospace and ocean engineering, that one day will be used for Navy and scientific applications. Stilwell and Woolsey also are collaborating to develop a fast 16-foot outboard motor boat that will be able to quickly and autonomously explore river systems as a reconnaissance scout.

"Field work with autonomous underwater vehicles is especially challenging because we cannot see the AUV when it is underway," Stilwell says. Among the challenges the researchers face are unknown drops and dips in ocean or river bottom surfaces, unseen debris, and bacteria and aquatic life. No one can stop a shark from taking a chomp on a spy drone. And power sources must last for months or even years. "We need to have confidence in our hardware and our algorithms so that the AUV completes its mission and returns home without human help."

For unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), much of Woolsey's work has focused on improving the performance and reliability of small robotic aircraft. The UAVs developed in Woolsey's laboratory have been used to demonstrate military applications, such as the collection of image and signal intelligence, and scientific applications, such as environmental monitoring. "One of the great advantages of both AUVs and UAVs," Woolsey says, "is that they can perform the dirty, dangerous, or dull missions cheaper and with less risk to life and property."

That mission, coupled with scientific endeavors, will keep Woolsey, Stillwell, and other engineering faculty members who build unmanned vehicles busy for years to come.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIRGINIA TECH'S CAREER AWARD WINNERS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following current and former Virginia Tech faculty members have won Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) awards from the National Science Foundation. This list is current as of November 2009.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Boris Vinatzer, assistant professor

Bingyu Zhao, assistant professor

College of Engineering

Masoud Agah, assistant professor

Godmar Back, assistant professor

Amy Bell*

Maura Borrego, assistant professor

Doug Bowman, associate professor

Ali Butt, assistant professor

Kirk Cameron, associate professor

Marc Edwards, Charles Lunsford Professor

George Filz, professor

Nakhiah Goulbourne*

Russell Green, associate professor

Dennis Hong, associate professor

Thomas Hou, associate professor

Michael Hsiao, professor

Scott Huxtable, assistant professor

Aditya Johri, assistant professor

Mark Jones, professor

John Lesko, professor

Mary Kasarda, associate professor

Donald Leo, associate dean of research

and graduate studies, professor

John C. Little, professor

Nancy Love*

Guo-Quan Lu, associate professor

Allen MacKenzie, assistant professor

Eva Marand, associate professor

Lindsey Marr, associate professor

Tom Martin, associate professor

Julio Martinez, associate professor

Leigh McCue, assistant professor

Leyla Nazhandali, assistant professor

Dimitrios Nikolopoulos, associate professor

Marie Paretti, assistant professor

Jung-Min Park, assistant professor

Mark Paul, assistant professor

Manuel Perez-Quinonez, associate professor

Amy Pruden-Bagchi, associate professor

Naren Ramakrishnan, associate department

head for graduate studies of computer

science, professor

Sanjay Raman, associate professor

Adrian Sandu, associate professor

|

Eunice Santos*

Patrick Schaumont, assistant professor

Sandeep Shukla, associate professor

Sunil Sinha, associate professor

Dan Stilwell, associate professor

Srinidhi Varadarajan, associate professor

Peter Vikesland, associate professor

Pavlos Vlachos, associate professor

Anil Vullikanti, assistant professor

Erik Westman, associate professor

Kimberly Williams, associate professor

Craig Woolsey, associate professor

Yong Xu, assistant professor

College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences

Kusum Singh, profesor

College of Science

Daniel Crawford, associate professor

Ignacio Moore, associate professor

Paul Deck, associate professor and director

of graduate studies

Alan Esker, associate professor

Carla Finkielstein, assistant professor

Serkan Gugercin, assistant professor

Jean Heremans, associate professor

Giti Khodaparast, associate professor

Gwen Lloyd, professor

Louis Madsen, assistant professor

John Morris, professor

Mark Pitt, professor

Theresa Reineke, associate professor

Ann Stevens, associate professor

Diego Troya, assistant professor

Edward Valeev, assistant professor

Myers-Lawson School of Construction

Michael Garvin, associate professor

Virginia Bioinformatics Institute

Iuliana Lazar, associate professor

Teresa Sylvina*

Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine

Taranjit Kaur, assistant professor

*No longer affiliated with Virginia Tech

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

STEVEN MACKAY is the college communications coordinator for the College of Engineering.

|