|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Flourish of Discovery

by DENISE YOUNG, ROMMELYN CONDE '07, and OLIVIA KASIK Photos by Jim Stroup

A remarkable microcosm of how private funding spurs innovation across the university is found in Latham Hall, home to 38 research teams and 200 researchers—faculty, postdoctoral, graduate, and undergraduate—from 10 departments in three colleges. Buzzing with the promise of discovery, the hall serves as an incubator for ideas. On the fourth floor, Amy Brunner, associate professor of forest resources and environmental conservation in the College of Natural Resources and Environment, studies trees at the microscopic level, tracing their genetics and identifying key genes that play a role in helping particular species grow stronger and faster. Without the private funding that supplied start-up equipment, Brunner's research would have lacked the necessary foundation to properly thrive. In fact, private funds supplied much of the equipment housed in the building's 84,277 square feet of space. That equipment will allow research teams to uncover safer insecticides to kill disease-spreading mosquitoes, improve watershed and riparian management, and discover how to recycle nitrogen from organic wastes without adverse environmental impacts—just a few of the many studies being conducted in Latham labs. "It's fair to say that the success of research in Latham is due to our ability to attract funds from diverse sources," said John McDowell, Latham Hall director and associate professor of molecular plant pathology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Those funds include a $5 million commitment from the building's namesakes, William C. "Bill" (general agriculture '56) and Elizabeth H. Latham, and generous support from such sources as commodity groups, growers associations, and private industry. The $5 million endowment from the Lathams will provide the college with laboratory equipment, undergraduate research stipends, graduate student fellowships, and other forms of support for years to come.

Brunner's lab looks like any other: stainless steel sinks, microscopes and computers, and carefully labeled drawers and cabinets. Student researchers focus carefully on their work. Discovering the secrets to tree DNA is no easy task. In the field of tree genomics, Brunner studies the genetic pathways of trees, finding ways to identify key genes and manipulate them to produce a desired result, such as a specific tree-crown architecture that results in greater biomass yield. Of particular interest are the species and hybrids of the genus Populus, commonly referred to as poplars, cottonwoods, and aspens. Because poplar is fast-growing (up to 12 feet per year), it also holds potential as a source for biofuels. "Startup funds were vital because when I came to the department [in 2005], no one was doing what I was doing," said Brunner. "That [funding] was really key." McDowell agreed. "These sorts of investments at an early stage in a faculty member's career are an essential factor. [The investments] are typically recouped many times fold." Once a gene is isolated and manipulated—say, to encourage a tree to take up nitrogen from the soil at a particular growth stage—several test plants are moved to the growth chamber down the hall. Some of the small shoots of plants will eventually make their way to a greenhouse on campus. Some will even take root at the Reynolds Homestead Agricultural and Research and Extension Center (AREC) for field testing. Private funds support the Reynolds Homestead, where the AREC is located. Without the AREC, forestry researchers like Brunner would be unable to examine how the tree genomics plays out in natural conditions. "It's really important, especially if you want to make your research translational—if you're trying to improve a biomass crop or understand the ability of a natural population to adapt to changing conditions. You need both the controlled conditions of a greenhouse and the natural conditions," said Brunner. Helping to meet a growing demand on a smaller land base, Brunner's research will one day translate to practical applications. As demand increases for wood, fiber, and biofuels, simply increasing the land base on which trees are grown isn't enough. "It's just not sustainable—or even feasible—in some places," said Brunner. Such groundbreaking research is often not possible without private support, noted McDowell. "Private funds allow researchers to explore ideas that federal sources of funding might be hesitant to support because [the ideas are] high-risk. Often times, seed money from private sources can fund the proof-of-concept experiments to show that an idea has merit." In other words, philanthropy provides the fertile soil for innovation to flourish.

Surrounded by the Jefferson National Forest, entomology graduate student Jake Bova focused his attention on a minuscule insect, the eastern tree hole mosquito. Although most people swat the air at the sight of a mosquito, Bova spent his summer placing traps to attract the detested insects. He conducts research on vector-borne diseases in mosquitoes and ticks, focusing on newly emerging diseases in Southwest Virginia. In the medical entomology lab in Latham Hall, Bova compares mosquito eggs to the number of adults collected. In the lab's insectary, he hatches the eggs and tests for rates of infection. Bova's research primarily centers on the La Crosse virus, a neurological disease passed on by adult mosquitoes to their eggs. When an infected mosquito bites a human, the transmitted virus can cause nausea, headaches, joint pain, and, in some cases, brain damage. "These symptoms happen in a lot of other diseases, so it may be very underreported. But we've seen [La Crosse] around here, and there's a need for it to be monitored," said Bova. As Bova continues to track the presence of La Crosse in the area, his research on the blacklegged tick is in its early stages. Blacklegged ticks carrying Lyme disease cause symptoms similar to those of La Crosse and other ailments, such as fever, fatigue, and skin rash. Severe cases can cause heart and nervous system damage. "It's still early in the process, and we'll need cooperation from the public to collect samples and assess the situation," Bova said. Research produced by Bova and his team in Latham Hall will help inform the development of surveillance programs for Virginia. Bova, whose grandfather also attended Tech, initially majored in building construction. Realizing his interests lay elsewhere, Bova found a better fit in entomology; with the support of a swimming scholarship, he earned his bachelor's degree in 2008. "I've always loved science, and the people in [the entomology] department have the passion for science that I was looking for." When he's not hatching mosquitoes and conducting tests, Bova teaches principles of biology undergraduate labs. He often relates his own research to class discussions. "I enjoy passing on knowledge and also learning from my students. I like the social interaction involved," he said. In a lab session on polymerase chain reactions—the process of producing copies of a DNA sequence—Bova used a YouTube video to explain the concept to students. "I remember being an undergrad and doing my best in classes where professors engaged their students, so I try to help facilitate that in my teaching." Bitten by the research bug, Bova plans to continue after graduate school, although not necessarily in academe. He entertains the thought of applying his research in the military. "There's a phenomenal preventive medicine program with the Army," he said. "I've always been intrigued about joining the military from that perspective."

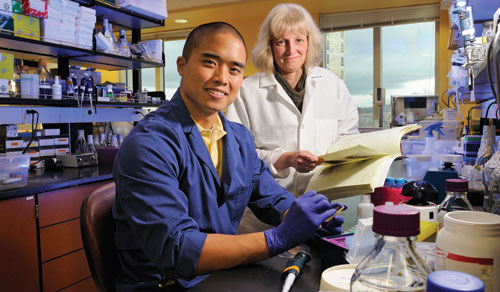

In a Latham lab run by biological sciences Associate Professor Dorothea Tholl, senior biological sciences major Tim Nguyen is examining the chemical communication of plants with their environment. More specifically, Nguyen is learning how phytochemicals protect the roots of plants against soil-borne pests and pathogens and exploring the cell-specific organization and molecular regulation of chemical defenses in roots. Funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Experiences for Undergraduates supplement, Nguyen's research project aims to uncover natural ways for plants to protect themselves from their "enemies." The goal is to eventually apply this knowledge to develop novel and sustainable pest/pathogen control strategies. Nguyen came to Tech as a business major, but he soon realized that any job revolving around office work was not for him. Remembering his affinity for playing outside and reading National Geographic as a child, Nguyen decided in his sophomore year to switch his major to biological sciences. He then began working in Tholl's lab as a summer intern in May 2010. He had discovered the opportunity through the Multicultural Academic Opportunities Program, an academic enrichment program that received additional gifts during the course of the campaign. Combined with Tholl's mentoring, the lab experience has helped Nguyen gain invaluable knowledge. "I've seen [Nguyen] grow in terms of his understanding of how to approach research, how to troubleshoot protocols and experimental approaches, and how to communicate with the graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and other scientists," Tholl said. In addition, Nguyen has gained experience in one of life's toughest lessons: time management. "Before I started working in the lab, sometimes I was productive, sometimes I wasn't. But the moment I started working in Dr. Tholl's lab, it forced me to be more efficient with the time I have," he said. Currently, Nguyen devotes about 10 to 15 hours per week to lab work. Tholl's lab team currently is comprised of one postdoctoral fellow, two graduate students, and three undergraduate students, including Nguyen. "Any student benefits from undergraduate research, not only [gaining] an understanding of lab skills and a sense of how things are done, but also [gaining] maturity and a sense of independence," she said. Tholl was recruited to Virginia Tech with the promise of funding to establish her lab—and she said that about $150,000 from the Fralin Life Science Institute fulfilled that promise. Several endowed Virginia Tech Foundation funds, such as one from Horace Fralin that provides more than a quarter-million dollars a year to the institute, support life sciences research across the university and allow students like Nguyen to benefit from undergraduate research experiences. In the spring 2012 semester, Nguyen will present his research at two undergraduate research conferences at Tech, the Molecular Plant Science Mini-Symposium and the Virginia Tech Biological Sciences Research Day. Following graduation, Nguyen intends to spend a year gaining clinical experience before applying to medical school. He looks forward to the challenge of medical school and even entertains the idea of becoming a surgeon. According to Tholl, Nguyen has acquired skills that will benefit him, no matter where his career takes him. "His undergraduate research experience has prepared him well for his future studies and professional development," said Tholl. In a Latham Hall growth chamber, rows of metal shelves house Plexiglas cubes, each carefully labeled and containing a tree seedling. The secret to the future of viable biofuels might one day grow out of this room. For Virginia Tech, such a discovery wouldn't be a first. New revelations appear every day in the labs and classrooms in Latham, where researchers are hard at work unearthing the mysteries of the sciences, from forestry to agriculture to biochemistry and more.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|