FEATURE

In early 1999, before widespread use of email and the Web, an elegant poster was mailed worldwide to the professional design community. Bearing photographer Bob Fitch's 1966 image of a pensive Martin Luther King Jr. superimposed over a familiar black-and-white image of King's "I Have a Dream" speech at the Lincoln Memorial—its steps and lawn and both sides of the Reflecting Pool awash in humanity—the poster announced an international design competition for the first memorial on the National Mall dedicated to an African American.

The announcement, which originated from Virginia Tech's Washington-Alexandria Architecture Center (WAAC), was an emotional milestone for the nation's oldest historically black fraternity. Some 15 years earlier, five leaders in Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. had voiced a dream to memorialize one of their most cherished brothers. To guide the project's development, the fraternity established a nonprofit fundraising entity, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation Inc., and set out to raise $120 million for the memorial's construction.

At WAAC, managing architectural competitions is one of the urban center's many outreach functions—and a serious undertaking that requires careful planning and considerable manpower. "The process is complicated," said WAAC founder Jaan Holt (architecture '64), the Patrick and Nancy Lathrop Professor of Architecture and longtime School of Architecture + Design faculty member and administrator. Holt has directed more than $1 million in sponsored projects and outreach-related activities at the center, which has its roots in a few design studios above a retail pharmacy in the Old Town neighborhood of Alexandria, Va., a core city in Tech's National Capital Region presence.

Since its formal launch in 1981, the Washington-Alexandria Architecture Center (WAAC) has offered more than 1,800 Virginia Tech students both real-world opportunities and course work toward advanced architecture degrees. Ushered into existence with strong support from then-dean of the College of Architecture and Urban Studies Charles W. Steger '69 (Virginia Tech's current president), WAAC continues to thrive in its urban location, retaining highly regarded faculty and outstanding architecture students as the college approaches its 50th anniversary in 2014.

Enacting the university's commitment to service as an integral part of education at a land-grant school, WAAC students have undertaken hundreds of thousands of hours of outreach and public service projects in the region, such as visiting sites that need attention and contributing ideas to refurbish worn spaces, according to center director Jaan Holt (architecture '64). Other projects have included documenting historic construction data for a variety of the region’s structures and managing a number of prominent design competitions.

Additionally, the über-successful Solar Decathlon, a national competition to encourage the construction of sustainable and affordable dwellings, was organized by WAAC faculty member and outreach coordinator Henry Hollander (architecture '89, M.Arch. '91), who also owns an award-winning design firm in Alexandria.

Deeply honored when approached by Alpha Phi Alpha in 1997, Holt was also well aware of the challenges ahead. "Initial stages of a competition are hardest [to fund]," he explained. "We had no money. Alpha Phi Alpha did not have great funding."

In light of the less-than-ideal fiscal landscape, Virginia Tech's involvement in those early stages was crucial, Holt said, adding, "I don't know if [the competition] would have taken off otherwise."

Since 1985, WAAC has hosted the only architectural consortium of its kind in the United States, the Consortium of Architecture Studies. Each year, the center's degree programs are opened to students and faculty from schools across the country and around the world.

"My first trip to WAAC on behalf of Virginia Tech was related to [the King Memorial design] project with Jaan Holt," said Vice President Emeritus of Multicultural Affairs Benjamin Dixon. Appointed in 1998 by then-President Paul E. Torgersen, Dixon, who led a new office charged with pulling together diversity efforts at the university, was a relative newcomer to Tech when talk of the design competition began to surface.

"I was at one of the first meetings of the consortium in preparation for the design competition," Dixon said. "Florida A&M University (FAMU) was part of the center's stable of professionals and schools, and there was Professor LaVerne Wells Bowie," of FAMU's School of Architecture. "I was looking at her, and she was looking at me. I was representing Virginia Tech as the first African American in central administration at the vice president level."

Because Bowie, who later served on the jury that selected the competition's winning design, was familiar with WAAC's management of the design competition for the Women in Military Service for America Memorial, she approached Alpha Phi Alpha on behalf of the center.

In Dixon's mind, the university's involvement in the design competition solidified in the right place at the right moment with the right people. Holt, for his part, feels that Dixon is one of those people. "Dr. Dixon gave us his whole discretionary budget, seed money to get things under way to research the project, get a team, get the site," Holt said. "That seed money got us going."

"I was new at the university," Dixon said. "I had not yet become fully enmeshed and had no outstanding obligations for the office to manage during that early phase of my tenure. Even if I had, I would have still seen [the project] as a significant opportunity to make a contribution. It really wasn't a tough decision."

With that seed money, along with grants from the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, WAAC assembled a team. Work to secure an appropriate site for the memorial commenced in earnest.

"For us to have responded so quickly to do this pro bono work impressed a lot of people outside the university," said Dixon. "That wasn't our aim, but it was a nice residual. We had the tools, the talents, and the purpose. It was a happy coming together of circumstances."

"When Alpha Phi Alpha first came to WAAC," Holt said, "they had no site. They had been offered a number of sites by the National Park Service and weren't happy with those selected by the Commission of Fine Arts, so our first challenge was to find an appropriate location."

Henry Hollander (architecture '89, M.Arch. '91), a faculty member and coordinator of outreach and alumni relations at the center, remembered that "there was controversy about the site selection. A whole group of folks wanted the King Memorial to the right of the Lincoln Memorial, where King had delivered his ‘I Have a Dream' speech."

While the location of King's speech is commemorated with a plaque, the planning group envisioned a much grander, more expansive site. After looking at the sites proposed by the park service, the WAAC team deemed most appropriate a 4-acre site next to the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial on the Tidal Basin. "We felt it was the best site, a triangle of acreage that sits between the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials, positioned in a continuation of the same polemics, the same political intentions, culminating in King's success in the civil rights movement," Holt said. "Alpha Phi Alpha liked that idea—a path of leadership around the basin, and King would be one of those leaders."

The site approved, plans were made for its official dedication. "We were asked if we could produce a bronze plaque for the dedication—in two weeks," Hollander said. While under construction, the site would need a marker indicating the vision for the area. "We scoured the Internet and found a foundry in Texas that was able to work with us in that short amount of time."

"Then we needed a base to hold the plaque at the site," continued Holt. "So we found a local headstone shop in Arlington, Va., that worked through the night to cut the base." Hollander said that he and Holt showed up at the National Mall and were "literally digging in the ground the night before the event. "

In the ensuing months, Holt and Bowie oversaw the surveying of the site and the coordination of aerial photography and climatology information. Meanwhile, with significant contributions from former graduate student Daryl Wells, WAAC designed promotional posters and programs for the competition.

In Holt's estimation, executing the King Memorial design competition in 2000 required between $150,000 and $200,000. Besides professional oversight, design competitions necessitate a robust workforce, in this case ably filled by architecture students both at the center and in Blacksburg. Without these students' dedication to the project, costs would have been exponentially higher.

Indeed, when the time had come to send information and design specifications to those who had registered to enter the competition, students on the Blacksburg campus assembled the packets and mailed them. Later, more than 50 students and faculty members participated in the setup of the design entries at the Verizon Center, then named the MCI Center, in Washington, D.C.

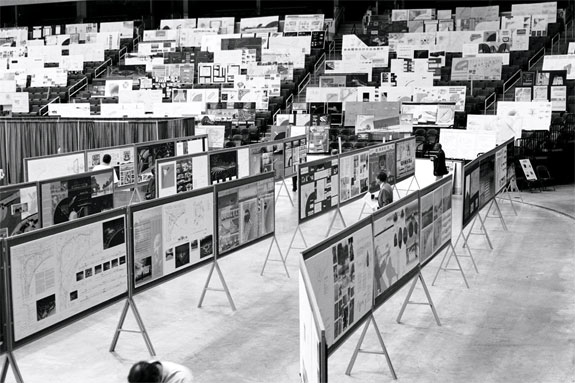

Response to the call for submissions was tremendous. Only the design competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial generated more entries than the King Memorial, which received more than 900 physically delivered entries.

Every entry was comprised of three 30-inch by 40-inch boards: one each for design, site layout, and information about the entrant(s). The Verizon Center "was consumed with submission boards from all over the world," said Holt.

The jury, an international mix of prominent architects and civic leaders, examined the boards for three days, identified approximately two-dozen finalists, and proceeded into a month-long evaluation period. On Sept. 10, 2000, the ROMA Design Group of San Francisco was announced as the winner of the competition, and WAAC's work was completed.

"Whatever we tried to do, people responded to the intent and nature of the project," Holt said. "Almost everyone was willing to work and contribute almost immediately. People were positive and would go out of their way to get things done. They never said, ‘This is impossible.' They figured out a way to do things, and we figured out a way to do things."

In 2006, following a span during which fundraising efforts wavered in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and then Hurricane Katrina, a formal groundbreaking for the King Memorial was held at the northwest edge of the Tidal Basin.

As part of the team assembled by the King Memorial Foundation to build the memorial, Ken Terry (civil engineering '94) of Tompkins Builders Inc. served as project executive, a role he also held in the construction of the World War II Memorial on the National Mall.

"I was extremely honored to have played a role in the completion of the design and construction of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial," said Terry, now a project executive with Grunley Construction Co. Inc. in Maryland. "The lengthy process was challenging and stressful at times, but the people involved, all working tirelessly with a common and worthy purpose, made it one of the most rewarding experiences of my life."

Officially dedicated on Oct. 16, 2011, the King Memorial joins the Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson, and Roosevelt memorials along the west portion of the National Mall. Visit the National Park Service to learn more.