AROUND THE DRILLFIELD

In a study published in July in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and the California Institute of Technology discovered that when they simulated market conditions for groups of investors, economic bubbles invariably formed. More remarkably, a correlation between specific brain activity patterns and sensitivity to those bubbles was found.

"Stock market bubbles form when people collectively overvalue something, creating what economist Alan Greenspan once famously called 'irrational exuberance,'" said Read Montague, director of the Human Neuroimaging Laboratory at the research institute and one of the study's senior authors. "Our experiments showed how the collective behavior of market participants created price bubbles, suggesting that neural activity might offer biomarkers for the evolution of such bubbles."

Montague and colleagues enrolled 320 subjects in a market-trading simulation game. Up to two dozen participants played in each of 16 market sessions, with two or three participants simultaneously having their brains scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, a noninvasive technique that allows scientists to use microscopic blood-flow measurements as a proxy for brain activity.

At some point during the 50 trading periods of each session, a price bubble would invariably form and crash. Although the scientists had suspected that crowd cognition would result in some bubble formation, they had not expected it to happen every time. Surprising the scientists even more were the distinctive brain activity patterns that emerged among the low earners and high earners.

The model may also shed light on other contexts in which groups or individuals overvalue something, Montague said. "This neurobehavioral metric could be used to help quantify situations in which people place excessive value on poor choices, such as drug addiction, compulsive gambling, or overeating," he said.

Montague, who uses computational models to understand neuropsychiatric conditions, noted that the study could not have been conducted without two relatively new additions to the neuroscientist's toolbox: fMRI and hyperscanning, a cloud-based platform that enables multiple subjects in different brain scanners to interact in real time—whether across rooms or across continents—and allows scientists to study live human interactions. Montague likens the technique, which he and his team developed just over a decade ago, to being able to eavesdrop on an entire cocktail party conversation, rather than the monologue fMRI enables.

A gender research associate in the Office of International Research, Education, and Development, Mary Harman Parks (M.S. geography '13) was trained to make maps—by hand.

In her fieldwork, Parks has approached some 100 international farmers—many of whom had never held a marker before—and asked them to draw maps. "In international development," Parks explains, "mapmaking can be a great way to learn about local people, their environment, and their way of doing things. Some people refer to these maps as mental maps or community maps, but most people in this field refer to them as participatory maps."

The maps, which depict the farmers' everyday lives, show crops, animals, homes and buildings, machinery, and even other people. A map of a woman's work environment in Uganda includes a kitchen, a chicken house, a bore hole, and the distilling drum, where beer is made, tucked under a tree.

From Virginia Tech News: Mary Parks' mapmaking takes her across the globe »

Learn more about Parks' research, and see other participatory maps on her blog »

The tooth of a phytosaur, a reptile, lodged about two inches deep in the thigh bone of a rauisuchid, a land-bound carnivore, has led researchers to question the long-held belief that these two dominant predators didn't interact some 210 million years ago.

In a paper published online in September 2014 in the German journal Naturwissenschaften, Stephanie Drumheller of the University of Tennessee and Michelle Stocker and Sterling Nesbitt, vertebrate paleontologists with Virginia Tech's Department of Geosciences, presented evidence that the two creatures not only interacted, but did so on purpose.

The researchers discovered the bone by chance at the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley. "Finding teeth embedded directly in fossil bone is very, very rare," Drumheller said. "This is the first time it's been identified among phytosaurs, and it gives us a smoking gun for interpreting this set of bite marks."

Added Stocker: "This research will call for us to go back and look at some of the assumptions we've had in regard to the Late Triassic ecosystems. … Aquatic and terrestrial distinctions were oversimplified, and I think we've made a case that the two spheres were intimately connected."

The Town of Blacksburg was ranked fourth on the "10 Happiest Small Places in America" list compiled by the national real estate blog Movoto.com. The rankings are based on seven criteria: stress factors (unemployment, commutes, and cost of living); personal safety (violent crimes per 100,000 people); percent of residents making greater than $25,000 annually; percent of married residents; home ownership; percent of residents with a bachelor's degree or higher; and walkability.

To those in the know, Blacksburg's quality of life is seldom far from praise—a happy circumstance that boosts Virginia Tech's ability to recruit and retain high-caliber faculty and staff.

Not only was Blacksburg ranked the "Best Place in the U.S. to Raise Kids" on a 2012 list in Bloomberg's Businessweek, Forbes.com named the Blacksburg-Christiansburg-Radford Metropolitan Statistical Area one of the best small areas to find employment, based on statistical data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And to nary a Hokie's surprise, in 2011, Southern Living included Blacksburg among the "Best College Towns in the South."

In similar fashion, Virginia Tech's efforts to ensure the well-being of both town and gown continue to attract their own accolades.

For the fifth consecutive year, the university received a gold award for its commuter program from Best Workplaces for Commuters, which encourages sustainable transportation. Last year, Virginia Tech landed the No. 1 spot on The Active Times' list of the "50 Fittest Colleges in America." And the year prior, the university and the area's economic opportunities were cited as major reasons for Blacksburg's top position on the "Top 10 Cities to Raise a Family" list on www.homes.com, a popular real estate site.

Hokies also endeavor to keep their neck of the woods as pretty as the town's. Virginia Tech's dedication to campus forestry management and environmental stewardship has earned the university recognition as a Tree Campus USA from the Arbor Day Foundation for the past three years.

With one in eight women likely to develop breast cancer in their lifetimes, finding better predictive markers remains critical. In a study published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Virginia Tech researchers in the Medical Informatics and Systems Division at the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute pinpoint diagnostic markers that may aid clinicians in better forecasting and preventing the disease.

Using breast cancer germline (blood) samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas Project and comparing them with samples from cancer-free individuals whose genomes are found in the 1000 Genomes Project, the research team identified several novel markers that not only may reveal risks for breast cancer, but also may yield therapeutic benefits.

"There is still a lot we can learn from looking at the human genome and how it can be affected in ways that may be associated with disease," said Natalie Fonville, a geneticist on the research team. "This study is the first of many in which we are engaged that identify subtle genomic changes that together may add up to cancer risk."

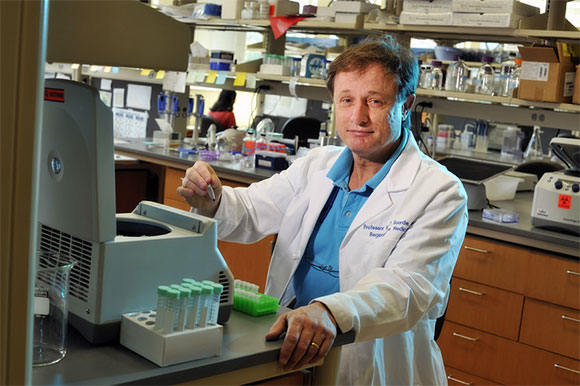

While examining how electricity moves through cardiac muscle, Robert Gourdie's research team developed a peptide that, as expected, enhanced the flow. Because other research had discovered similar proteins that supported healing, the scientists then scratched a single layer of skin cells lying on a Petri dish, applied their peptide, and waited. The cells began mending.

"We had this fundamental question: How does electricity flow through the heart? We had no idea the answer would lead to a treatment for healing skin wounds," said Gourdie, director of the newly expanded Center for Heart and Regenerative Medicine Research at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute.

While early clinical trials using the peptide on diabetic foot ulcers have been promising, with the potential for wounds to heal in half the time, the treatment must progress through additional trials before it can be made available for wider use.

Virginia Tech's groundbreaking 1973 decision to admit women into the Corps of Cadets not only predated the U.S. service academies by a year, but also led to another first for the university in 1981—a first that can also be considered a "last."

Living in a separate residence hall from the males, female cadets in corps leadership roles found it increasingly difficult to fulfill their supervisory responsibilities. In response, the Board of Visitors backed off its hard-line policy of separating the sexes and allowed Brodie Hall to house both men and women.

Tech, however, was well behind the curve in this area. Said then-Vice President for Student Affairs James Dean, "We are the last university in the state and perhaps the last in the East that doesn't have some form of coeducational living."

But the die had been cast, and the commingling of genders soon spread to the civilian student body. In fall 1983, East Ambler Johnston became Virginia Tech's first non-cadet residence hall to go coed.

Produced by University Relations