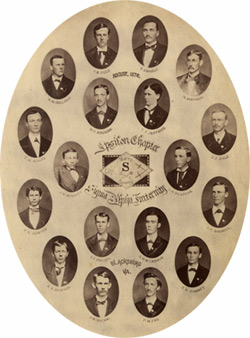

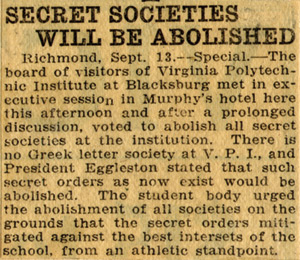

Technically, in the eyes of the university, the latter is correct--because that's the year fraternities and sororities were officially recognized as legitimate organizations. In reality, though, students have belonged to fraternities since shortly after the college was founded. Confused? Read on for a look at the tangled evolution of today's fraternity and sorority life. Unrecognized, but undeterred When Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (VAMC) ended its first academic session in 1873, there weren't many activities for its 132 students other than studying. The college's only official organizations were the Maury and Lee Literary Societies, which focused on public speaking, and VAMC's rural location translated into a scarcity of social outlets. That situation changed when four students contacted the national fraternity Pi Kappa Alpha for approval to establish a chapter at VAMC and received the nod to do so during the 1873-74 academic session. Soon afterward, two other national fraternities, Kappa Sigma and Sigma Alpha, were established on campus, and by the end of the 1874 session, 19 percent of the student body--including more than 50 percent of the cadet officers--belonged to one of the three fraternities. A mere two years later, 28 percent of the student body and 67 percent of cadet officers belonged to fraternities. A fourth fraternity, Beta Theta Pi, was founded on campus in 1877--the same year the college began having financial and other difficulties, including dissension among college faculty members over the issue of rapidly deteriorating student discipline. Gen. James H. Lane, professor of military tactics, and several faculty members championed the idea of organizing the college as a military academy. But other faculty members--including President Charles L.C. Minor--adamantly opposed the idea, and the escalating tension between the two factions led to a highly publicized fistfight between Minor and Lane. Many parents withdrew their sons, and enrollment, which had been slipping since the 1876-77 session, dropped to an all-time low of 50 students in 1879-80. Realizing that a drastic solution was needed, the VAMC board in 1880 adopted a strict military system that required all students to live on campus. Because of fears that fraternities might undermine the new system, the board also passed a regulation that "No student, during his connection with the college, shall belong to any secret college society, nor in an association, except such as shall have been approved by the faculty." However, the college's students were nothing if not enterprising, and in 1893, they established a dance club they called the German Club, after a type of formal dancing popular at the time. Twenty years later, other students formed a competing organization, the Cotillion Club. Although the dance clubs, along with several other small organizations, didn't bear Greek letters, they were in many ways similar to fraternities.

The changing student body created a need for additional social outlets, and, as with the original fraternities, local Greek organizations satisfied that demand. Smoot says that by the late 1960s, "it had gotten to the point where many students who were in leadership positions were in fraternities, and those of us who were in the Student Government Association (SGA) started a platform for the university to recognize us." In 1967, an SGA poll of campus residents showed strong support for recognition of Greek organizations. The University Council put the issue to a student vote in 1969, but the measure was defeated, in part because the local fraternities were unhappy that the proposal called for them to move on campus. Another version that allowed for off-campus fraternities passed muster in 1971, and in May 1972, the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors approved the plan. For the first time in nearly 100 years, the school officially recognized its Greek organizations. Growing pains The official go-ahead caused Greek chapters to explode onto the Virginia Tech social scene. By the end of 1972, the university recognized 18 national fraternities, five local fraternities, and eight sororities. The following year, the national historically black fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, was chartered on campus. As the university's first coordinator for fraternities and sororities, Smoot worked with the local fraternities to affiliate them with national organizations. Vice President of Alumni Relations Tom Tillar (biology '69; M.A. student personnel services '73; Ed.D. administrative and educational services '78), who succeeded Smoot in that position, says, "There was a big difference between the goals of the local and the national fraternities. Converting to a national meant accepting oversight from a national organization. It was smooth for most, but some were resistant." One example was Sigma Lambda, the popular local fraternity founded in 1947, which disbanded in 1974 after its members decided not to affiliate with a national organization. One former member says, "When the question came up about going national, there was a unanimous, resounding 'Hell no!'"

According to Pi Kappa Phi alumnus Phillip Barnard Jr. (geology '83), the public image of the party house led the university to crack down on Greek organizations. His fraternity held an annual competition called the "Guzzell Cup," the object of which was for teams to consume the most 12-ounce beers in an hour. In 1980, a Collegiate Times photographer working on a piece about excessive drinking at Greek functions publicized the event, which "was used by the university as the prime example of just how excessive the Greek community had become during its first 10 years of existence at Virginia Tech," Barnard says. The Guzzell Cup was permanently retired, and many Greek organizations began to tone down the public nature of their parties, he notes. In 1985, the Commonwealth of Virginia raised the drinking age to 21 for people born on or after July 1, 1966, and in 1987 raised it to 21 for everyone. As a result, Barnard says, "The university mandated that Greeks start having rush parties with no alcohol whatsoever. The era of the private, uncontrolled house party was over for the Greeks." Aside from drinking, another perception of fraternities and sororities was that they were exclusionist. Frank Illig (accounting '83) says that his only negative experience was "when a friend rushed and was not given an invitation to pledge. It heightened my realization that I had two social 'worlds,' my fraternity and my non-fraternity friends." As for hazing, it seems to have been more of an issue for the local fraternities before official recognition, although one alumnus remembers that the Interfraternity Council (IFC), the governing body for traditional fraternities, focused on the problem in the mid '80s. However, despite the sometimes negative image of the first years of official Greek life at the university, more than 120 alumni who belonged to fraternities and sororities during the 1970s-80s and contacted Virginia Tech Magazine about their experience shared positive memories. "What I remember the most is having a place to go during the day between classes to talk to our brothers or play cards, horseshoes, or volleyball," says Illig. "You knew when you went there, you were among family you could trust and rely on, regardless of the issue." Greek revival? Today, Virginia Tech's Greek system is the 19th largest in the country, with 12 sororities in the Panhellenic Council, 31 fraternities in the IFC, eight in the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC)--which governs traditional black fraternities and sororities--and, currently, nine in a new governing body, the Council for Unified Fraternities and Sororities (CUFS). (See "Something for everyone,") Student body membership in traditional fraternities and sororities has ranged from 10-12 percent since official university recognition and rose to more than 13 percent this fall. As a step toward becoming more proactive with its fraternities and sororities, the university recently created the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life. Assistant Director Patrick Romero-Aldaz (M.A. educational leadership and policy studies '01), who works with the Panhellenic Council and the CUFS, believes the reorganization will make a big difference. "We realize how truly young we are as a Greek community and that we still have a lot of growing to do, but for the first time, we have a full staff committed to developing the organizations in a positive direction for the students, the chapters, and the community." One example of positive change is that today's potential pledge does not rush a fraternity or sorority but is instead recruited. "We feel that 'rush' has a bad connotation," explains Panhellenic Council President Erin Kennedy. "This lets the girls know they're not rushing us, we're recruiting them." Will Wright, president of the IFC, agrees with the change. "'Rush' is a process where you rest on your laurels, while recruitment is more of an active process." Another difference, Wright adds, is that students today "seem to be more academically inclined," pointing out that individual chapters offer scholarships, set up study hours, and are held accountable for their members' grades. As of spring 2003, students in fraternities and sororities were doing at least as well as, if not better than, the overall student body. The all-fraternity grade point average was 2.86, compared to the all-male undergraduate average of 2.91, and the all-sorority was 3.13, topping the all-female undergraduate average of 3.12. Ed Spencer, assistant vice president for student affairs and associate professor of higher education and student affairs, says that today's students want to join a fraternity or sorority for different reasons than their parents. "Today, they're more team oriented and service oriented." Spencer, who oversees the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life, says that his philosophy on members of Greek organizations is the same as with all students. "We're here to teach students and help them grow and mature," he explains. "If something is not as it's supposed to be, we first give them a chance to take care of it. If they don't, then we step in. We don't want to be policemen--we want to give them the opportunity to be responsible for themselves." Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life Director Eric Norman says--knocking on wood--that Virginia Tech has been "really lucky" that its Greeks have not received the type of negative publicity that the system has nationwide, such as with underage or binge drinking and hazing. This may be due, in part, to the fact that the organizations hold their members to "enormously high standards in terms of risk management," says Kurt Alan Bell, IFC director of membership development. In addition to familiarizing new members with the organization's stringent guidelines, Bell points out that the IFC conducts programs to educate pledges about scholarship and career searching, as well as alcohol awareness and sexual assault. "Our new members are exposed to more sophisticated programming than any other student organization," he says. At Bell's request, Lt. Wendell Flinchum, special events coordinator for the Virginia Tech Police Department, recently participated in an IFC program on alcohol awareness. "We accept that there are people who are going to drink, so we preach, 'if you drink, do it responsibly,'" Flinchum explains. Having been on the Virginia Tech police force for 19 years, Flinchum reflects that, overall, the department has far fewer problems with today's Greeks than it did 15 years ago. "At that time, the university didn't exercise quite the control [over Greeks] that it does now," he says. "Today, [fraternity and sorority members] are pretty representative of the student body and don't cause any more problems than other students." Still, combating the traditional stereotype of Greeks certainly isn't helped by shows such as MTV's "Fraternity Life" and "Sorority Life"--which, Spencer points out, focus on local, not national, chapters. Kennedy says the shows certainly don't help with recruitment. "If that's what I saw, I wouldn't want to join, either. We hate [that image]." Kappa Alpha Theta alumna Karin Horstman Johnes (family and child development '95; M.Ed. educational leadership and policy studies '03), the director of Greek life at Washington University, says she fights that negative image every day. "Fraternities and sororities are the one community that it's considered 'pc' to bash and make stereotypes about. And that's frustrating." Norman, however, can see a benefit from the negative publicity Greeks have received throughout the years. "In some ways, the negative press may actually be helping administrators steer the students back to the basics, letting us say, 'We can't continue to do things the way we have been.'" Looking to the past to forge the future The founding ideals, such as philanthropy and community service, says Horstman Johnes, are what Greek organizations are truly about. "I really believe in what fraternities and sororities can be. They have profound values." There is no question that fraternities and sororities donate time and money to philanthropic and community service events--nationwide, they are the largest network of volunteers in the United States, logging 10 million hours of service a year. Each Virginia Tech chapter has at least one chosen philanthropy project, which can range from Zeta Tau Alpha sorority's national philanthropy, the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, for which the chapter holds several events a year, to the foundation founded by the national Pi Kappa Phi fraternity, Push America, which seeks to raise awareness of and money for people with disabilities. On a local level, Tech's fraternities and sororities stay involved with the community. Alpha Phi Omega sorority, along with the German Club, holds a "Senior Prom," which is described as "an afternoon of dancing and good times" at Friendship Manor Retirement Home. Each spring, Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity conducts a Flex Out Hunger Program, where Tech students can donate money from their dining plans in the form of food certificates for the Montgomery County Emergency Assistance Program. And the NPHC holds an annual Christmas party for underprivileged children in the area. It is these positive aspects of fraternity and sorority life, Romero-Aldaz says, that Virginia Tech's fraternities and sororities are "trying to get back to--their founding ideals, which are leadership and service to the community." That's what makes up today's Virginia Tech fraternity or sorority member. As for tomorrow's? "We want to make this the exemplary Greek system for the United States," Norman says enthusiastically. "We have the tools, we just need the time."

Once fraternities and sororities were officially recognized at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg town officials hoped the university would move the houses onto campus. For years, the town had battled the fact that a group of students could rent a structure, hang out Greek letters, and call itself a fraternity, and it even passed an ordinance requiring that a group own a two-acre-minimum piece of land before it could do so. However, it took the university some time to comply with the town's hopes--the first three houses moved onto campus in the early '80s, and by the end of the decade, there were 10. Today, the Oak Lane Community, located in the northwest sector of campus past the overflow parking off Duck Pond Drive, is comprised of six fraternities and all 12 of Tech's sororities. The groups lease their houses from the university, which, says Ed Spencer, assistant vice president for student affairs, "makes on-campus housing affordable." Fraternity and sorority members who live in an Oak Lane house think the community offers them a great deal. In addition to providing a cost-effective housing solution, "It gives more people on campus the chance to see the Greek community," says Will Wright, president of the Interfraternity Council. Panhellenic Council President Erin Kennedy adds, "It's definitely a good thing. The university does a good job of maintaining the houses. And it's neat to have a community of students sharing goals." The Oak Lane Community, which has won several national awards, serves as a model for other universities--Spencer says that so many schools have asked to see the plan for the community that his office has put together a formal inquiry packet. "Oak Lane represents $22 million of property that was deliberately engineered to provide economic housing for Greeks," he says. "It's the university's statement of support for the Greek system." Two of Virginia Tech's four Greek governing bodies, the National PanHellenic Council (NPHC) and the Council of Unified Fraternities and Sororities (CUFS), oversee fraternities and sororities that provide a diverse array of options for Virginia Tech students. The National PanHellenic Council, like the IFC and the Panhellenic Council, answers to a national organization, and it governs Virginia Tech's eight traditionally black fraternities and sororities. Rebecca Obeng, president of the NPHC and a member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, says she made the decision to join a traditionally black sorority to "become more involved with campus events and black awareness issues. The benefit of joining a black organization, as far as diversifying the campus, is to ensure that there will be a voice or idea of diversity," she adds. The same idea fueled the creation of the CUFS, which, compared to the evolution of the other governing councils at Virginia Tech, emerged overnight. When Tech student Takiyah Nur Amin transferred from the University of Buffalo last year, she noticed that there wasn't a leadership venue for the university's special interest groups, so she created the CUFS. At the beginning of the spring 2003 semester, there were six organizations; today, says Patrick Romero-Aldaz, "we're looking at 14-15 groups to belong to CUFS by the end of the year." The groups, he says, "range from traditional cultural groups, such as Delta Phi Omega, a sorority for South Asian students, to faith-based organizations, such as Phi Gamma Gamma, a Christian service fraternity." While forming such small, interest-specific groups could potentially be seen as a form of self-segregation, Romero-Aldaz says that the students and administrators from the four governing bodies are actively working to bring all Greek students together. "In terms of admissions and recruiting for the university, it's great to have a venue for all groups," he adds. "We say there's a place for everybody in fraternity and sorority life--this really solidifies that. Our vision is that we further identify another opportunity for students. All organizations feel that students need to join groups where they're most comfortable."

Before I came to Virginia Tech, my impression of college fraternities stemmed from sources like the 1978 movie "Animal House." I soon realized, however, that the fraternity of the 21st century is vastly different from its Hollywood counterpart. During my first year at Tech, most of my hall-mates were upperclassmen, which created a much different social atmosphere from the average freshman hall. I started to consider joining a fraternity to meet people whom I had more in common with, and when I met the brothers of Phi Delta Theta during fall 1999 recruitment, I could see myself being friends with them, so it made sense to pledge. I discovered many advantages to joining a fraternity besides gaining a couple of drinking buddies. "Going Greek" promotes close friendships, creates leadership roles, and encourages academic achievement and athletic competition. The network of brothers within a fraternity also leads to programs that would be much more difficult to organize with just a few friends, such as getting group tickets to football games, having a shift-based designated driver system, and contributing to charities. Being in a fraternity also allows me to enjoy the sense of a community that would be found at a much smaller school. I hardly ever travel across campus without seeing somebody I know, and some of the best friendships that I have made at Tech began through a connection to the fraternity. The Greek community at Tech is so expansive that those who wish to do so will find the group of people with whom they most identify. With 59 fraternities and sororities on campus, those who wish to join are certain to find the right option. Just as with every organization or club, Greek life may not be right for everyone, but it was definitely the right choice for me. John Yowell is a senior English major and an intern for Virginia Tech Magazine.

|