EIGHT THINGS Horse Racing Stewards Do

Odds were squarely at even money that Erinn Higgins (animal sciences '09, M.S. '11), a native of Saratoga Springs, New York, would pursue a career in the thoroughbred horse racing industry.

The daughter of a trainer and an exercise rider—and the great-niece of National Museum of Racing's Hall of Fame trainer Charlie Whittingham—Higgins made history last year as the first female to serve as a steward at the New York Racing Association's three tracks: Aqueduct, Belmont, and Saratoga.

Having completed the Racing Officials Accreditation Program in 2014, Higgins currently serves the New York State Gaming Commission as the alternate steward at Finger Lakes Racetrack in Farmington.

1) It is standard practice for a racetrack to have three stewards who oversee races, much like referees in other sports.

2) During each race, the stewards watch for any incident or infraction, including issues at the starting gate, that may have affected the race's outcome.

3) If an incident or infraction occurs during a race, the stewards will launch an inquiry. Jockeys can also lodge an objection against another rider or horse if they feel their horse's progress was impeded. As with all competition, fouls do occur.

4) Upon an inquiry or claim of foul, the stewards review the race video—multiple angles of each race are recorded by cameras placed in various spots around the track.

5) By way of a phone near the finish line, the stewards also talk to the jockeys involved.

6) Based on the information gathered, the three stewards decide whether to disqualify the horse in question.

7) Stewards can suspend jockeys for infractions during the course of the race.

8) To ensure compliance with all rules and regulations, stewards also serve as a regulatory body overseeing the conduct of all licensees at the track, including jockeys, trainers, owners, and grooms.

Following a contentious stretch run in the 2015 Fountain of Youth Stakes at Florida's Gulfstream Park, a stewards' inquiry was immediately launched, and one of the jockeys lodged an objection. Although first to cross the wire, the colt Upstart was disqualified for impeding Itsaknockout, who was declared the winner.

How-to

Balancing acts

Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge | Massachusetts

As manager of Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge, a trio of islands stretching eight miles off the elbow of Cape Cod, Matthew Hillman (M.S. fisheries and wildlife sciences '12) maintains critical habitat for migratory shorebirds, sea ducks, spawning horseshoe crabs, and a variety of other protected species.

Operating a 7,604-acre refuge near one of New England's historic recreational playgrounds takes more than just a focus on wildlife. Hillman also must manage relations with nearby residents and visitors, some of whom bristle at restrictions on activities around the islands. For instance, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently prohibited kiteboarding because it disrupts the nesting, resting, and foraging activities of resident and migratory birds.

Here's how Hillman manages to get buy-in from local residents and governments while still honoring the refuge's mission to preserve habitat and wilderness.

1) Educate the public about Monomoy's ecological role and encourage activities consistent with that role: "We have to allow people to understand the refuge is open to public uses appropriate to the refuge—canoeing, kayaking, hiking on the islands, birdwatching. We do want people to come to the refuge and stop by the visitors center to understand why it's so important, not just for Massachusetts and New England, but on a hemisphere scale. This is a crucial place for birds, not only to nest, but to stop over during migration."

2) Draw the line when necessary, but use the moment as an opportunity to teach: "To use the kiteboard example, there are places where people can kiteboard on Cape Cod and even not that far from the refuge, but the wildlife refuge is not an appropriate place. It falls on us to educate those users not just that it's not appropriate, but why. That can take the form of signage, of public presentations, news articles—any way we can get the word out—while at the same time encouraging uses that do benefit the public and wildlife alike."

3) Find ways to engage people's imagination: "The nonprofit Friends of Monomoy applied for and won a grant to install a remote video camera in our common tern colony, which is one of the largest on the Eastern Seaboard. Because the birds nest on offshore islands, and in season those colonies are closed off to public access, it's hard for people to fully appreciate these bird colonies. The video camera will provide a live feed so the public can get some understanding of how unique and how important that offshore colony is to the terns."

4) Emphasize the positives that come with the wilderness designation, the highest level of federal land protection, which prohibits motorized equipment and vehicles: "A lot of users appreciate being able to go to Monomoy, where they don't have to deal with anything like a weed whacker or ATV driving by. It's rare to have an 8-mile stretch of beach that's completely and totally natural, no sea walls, no vehicles. You can go and experience this wilderness character for yourself, just by being there. That's something that a lot of our visitors really love."

Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge on Facebook →

Grade: B+

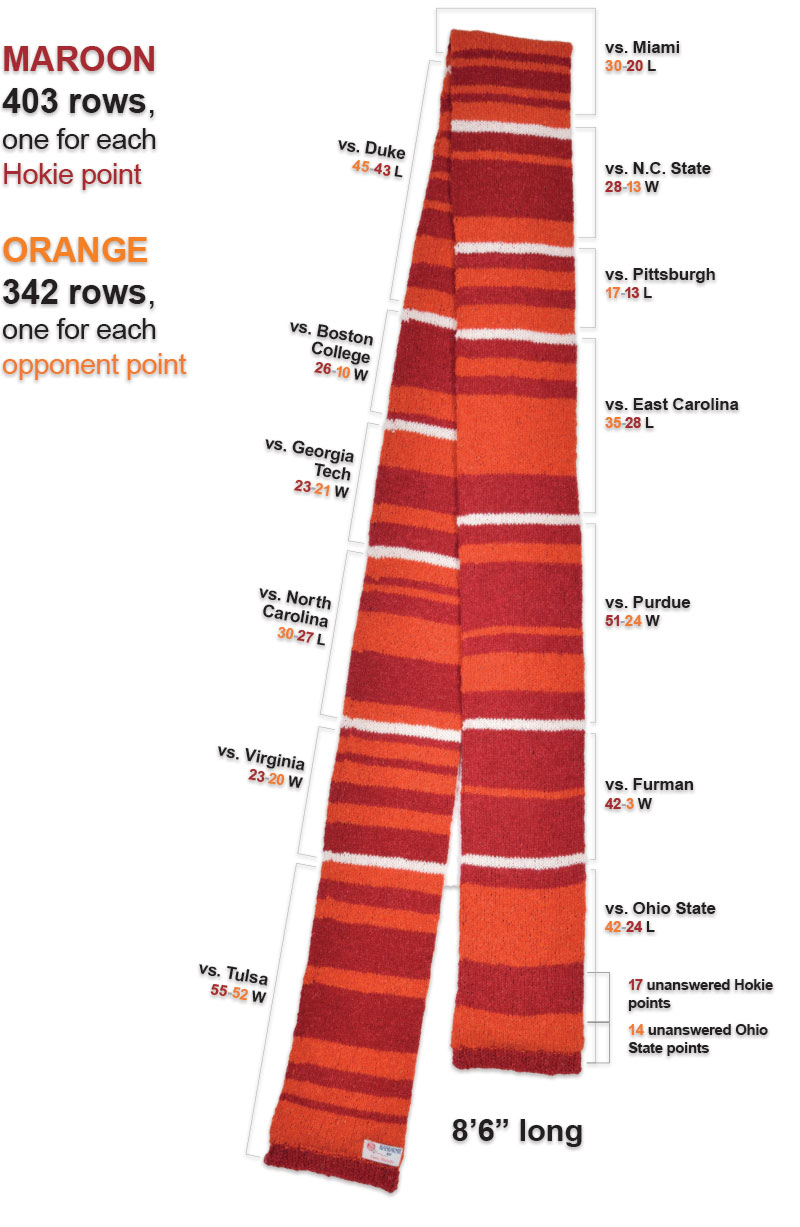

Fan knits season's scores

"What's a Hokie spouse of 40 years to do after all these years of Hokie football? Knit a scoreboard scarf for the 2015 season! I watched every game, knitting as the scores unfolded. … Why a B-plus? It was great to commemorate Coach Beamer's last season, but I wish we would've won more games."

— Michelle Trahan, wife of Jim Taylor (architecture '73), got the idea from scoreboardkal.com. Michelle loaned the scarf to their friends Jim (architecture '72) and Leslie Maitland, who will show it off in Lane Stadium this fall.

Moment

Paddling upstream

Two recent Virginia Tech alumni put their training and service ethic to work during a 500-mile kayaking expedition to assist the launch a non-profit environmental organization.

Alex Crooks (natural resources conservation and environmental education '12) and Stephen Eren (natural resource recreation and forestry '11) organized, supported, and participated in a month-long circumnavigation of the Delmarva Peninsula. For 30 days in September and October 2015, they paddled with Don Baugh, Walter Brown, and others who dropped in and out to launch Upstream Alliance, which recruits and trains emerging leaders in environmental education, stewardship, and advocacy. The trip lasted 30 days in September and October 2015, after which Crooks and Eren moved on to other pursuits.

Crooks and Eren used satellite photos to plan the trip and coordinated with landowners along the way to find places for the group to camp. They tested water samples, swept with a sein net to catalog fish and wildlife, and conducted regular "sneaker tests" during the trip.

Virginia Tech Magazine spoke with Crooks about the experience.

What is the "sneaker test," exactly?

"The 'sneaker test' was made famous by a previous senator [former Maryland State Sen. Bernie Fowler]. You wear white sneakers, and then you walk in until you can't see your sneakers anymore. It measures turbidity, and it's something the senator has done for over 30 years. He came out to wish us luck on our trip. We didn't do a sneaker test every day, but we used a secchi disk instead. It's basically the same thing, a disc with black and white, where you lower it until you can't see it anymore. The more you can see down, the healthier that water is going to be."

What were your days like?

"We were collecting water-quality data and posting it every single day. We were writing blog posts so people could follow along. We'd paddle anywhere between 10 and 27 miles a day. As soon as we got to our campsite, Stephen and I would unload our boats, set up camp, and start cooking dinner as soon as possible. Once dinner was finished, Stephen and I would set up our tents. We had a lot of visitors come. They brought local food, local wine, fresh-caught fish."

Is there any one memory or moment that stands out for you?

"The morning when we had our biggest group, we had seven kayaks, about 15 people total. We woke up at 4 a.m. and scurried to put our tent away, pack our lunch, and be on the water by 5 a.m., so we got to see the water rise on the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. You see the huge freighters filled with shipping folks and the big metal crates they're taking up to Baltimore and the port of Philadelphia. They're just enormous, like 20 stories tall. We got to watch as the sun came up and was changing the colors of the sky. It was awesome paddling, but it also turned into our hardest day. A Nor'easter coming through made the water super-choppy. It was only supposed to be an 11-mile day, but our campsite fell through at the last minute, so we had to paddle to another one, and it ended up being our 27-mile day. I had a wrist injury, so it killed me to paddle through."

I understand you also got caught in Hurricane Joaquin?

"We were on Smith Island when Joaquin came through, and we stayed there for four days. During that time, all of the community members took us in. We hired one lady to cook us dinner one night to put some money back into the Smith Island economy. The last night, we went to the town store and bought as much as we could and threw a huge hurricane party for eight or nine people, with steak and all kinds of vegetables."

What else will you remember?

"Another moment for me that was personally really amazing: We'd gone through another long paddle, trying to get to this cabin, but the Nor'easter was still affecting the weather. We went the wrong way in the marsh. It's like a maze, and if you go the wrong way, you're screwed. These fishermen came through and helped us back. They hauled my kayak because I had the wrist injury. They brought us to a cabin surrounded by marsh. It was about 200 yards away from an outlet on the ocean. The fisherman told us the story of the cabin, how it was pieced together from driftwood and passed down for generations. They used pieces of furniture and cabins that had been destroyed to put it together. There was no electricity, but it was a place these families came year after year to go hunting and fishing.

"Another time we had just gotten out of Delaware Bay and were on Atlantic Ocean, about 200 yards away from the beach in Ocean City [Maryland], and we just were surrounded by probably 30 porpoises that completely encircled our kayaking group. That came at a particularly challenging moment of exhaustion, after days and days of paddling. They popped up right when we needed it."

More Upstream Alliance videos →

Retro

By Kim Bassler '12, communications coordinator for University Libraries. Images are courtesy of the libraries' Special Collections; more can be found at imagebase.lib.vt.edu.

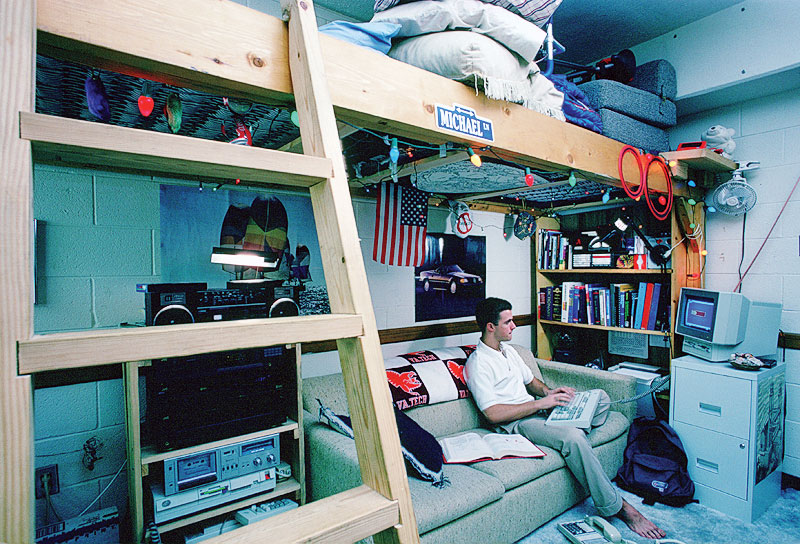

26 years ago,

students' technology needs in their dorm rooms were quite different from today's needs.

28 years ago,

the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI), then called the Center for Transportation Research, was founded. Shortly after, Tech began developing plans for the Smart Road, an "electronically monitored highway of the future." Today, VTTI leads the way in autonomous vehicle technology.

30 years ago,

Virginia Tech celebrated Founders Day with a visit from Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. Beginning in 1972, the university used Founders Day to recognize outstanding faculty and alumni and, later, outstanding staff and students.

30 years ago,

students thought a sailing skateboard might be a creative way to get around campus.