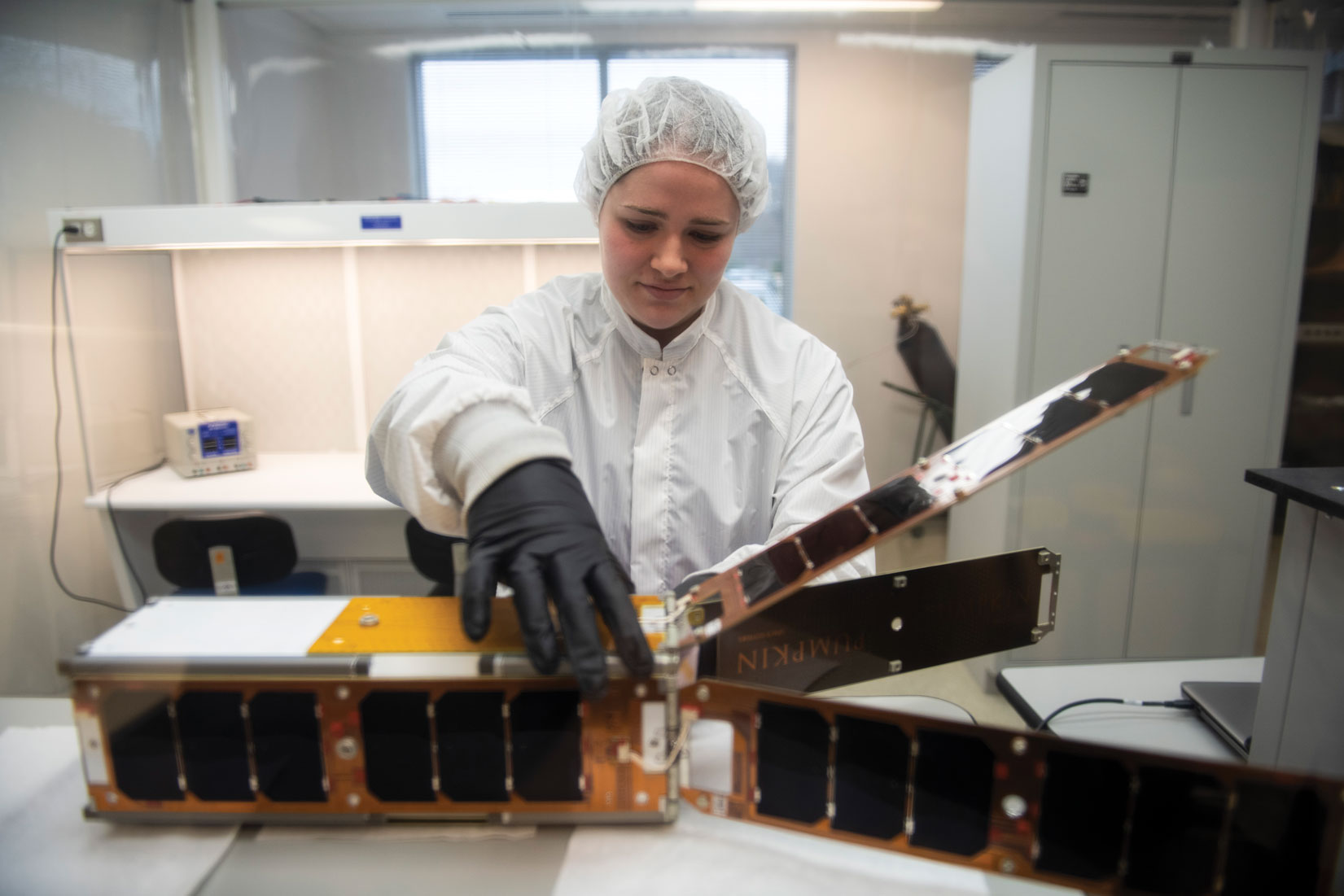

Cubesat Constellation: Virginia Tech’s satellite—the first to be built by undergraduate students and launched into space—along with two satellites from other Virginia universities was deployed from the International Space Station in July 2019. Working together as a constellation, the three nano-satellites are each about four inches cubed and weigh approximately three pounds.

By Mason Adams and Jenny Boone

The dream of slipping the bonds of gravity to escape Earth and venture into space has inspired humanity for centuries, uniting scientists, explorers, and dreamers; accelerating technological advancement; and propelling new worlds of research and development.

Hokies have played key roles in the world’s advance beyond the clouds, flying as astronauts, leading missions from the ground, and participating in the thousands of support and science roles required to launch humans into space and bring them back safely.

The university’s land-grant mission to serve humanity, as well as its strengths in engineering and other flight-related disciplines, continue to play an important role in aeronautics and space exploration.

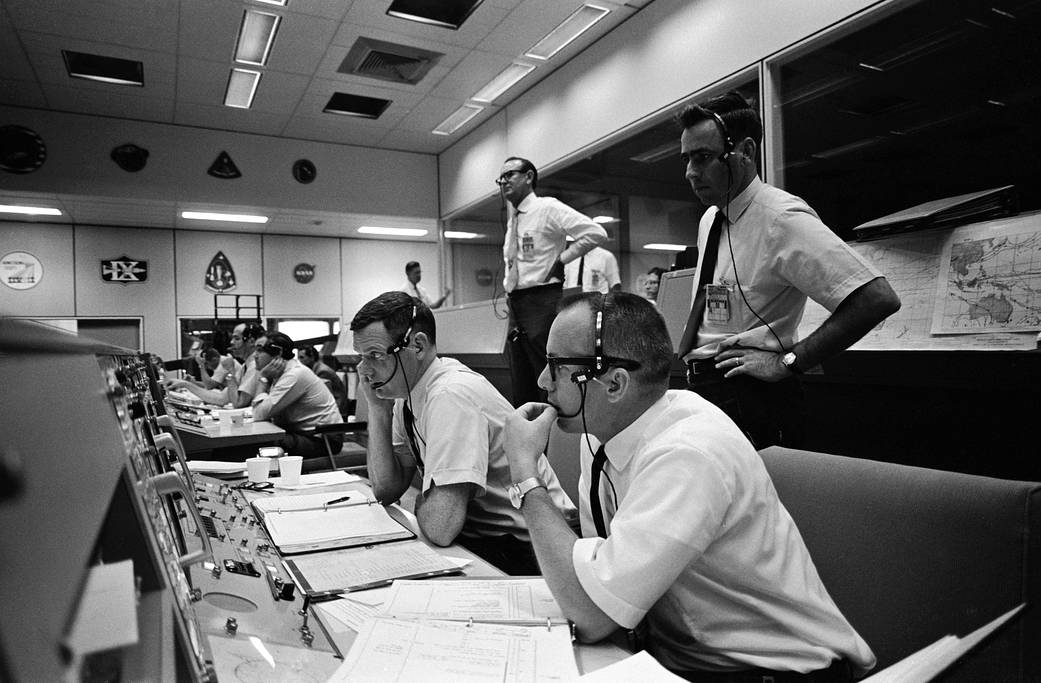

“Scientists say there is no life on the moon. I look at the moon today, see the faces from NASA, industry, science, and academe who brilliantly sent Americans to that place, and I know differently. The people of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo are blossoms on the moon. Their spirits will live there forever. I was part of the crowd, then part of leadership that opened space travel to human beings. We threw a narrow flash of light across our nation’s history. I was there at the best of times."

—The late Christopher Kraft ’44 from his 2001 autobiography “Flight: My Life In Mission Control”

Christopher Kraft (NASA)

Virginia Tech’s foray into flight began when a flying field was established near the university in 1913, just 10 years after the Wright Brothers’ historic North Carolina flight. In 1926, then-Virginia Tech President Julian Burruss appointed a faculty committee to take the first steps toward planning an aeronautics program and considering sites for a landing field. As a result, construction of what is today the Virginia Tech airport began in 1929; that same year, the university began offering aeronautics courses under the mechanical engineering curriculum.

In 1941, aeronautical engineering became a separate curriculum, and within two years it was named an academic department.

NASA legend Christopher Kraft ’44, who is remembered as the founding father of mission control, earned his degree from the new department before joining the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA)—the precursor of NASA.

Kraft, who died in July 2019, went on to become NASA’s first director of flight operations in the 1960s, and he was instrumental in landing an astronaut on the moon. Later, he became director of the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Kraft is credited with developing the mission planning and control processes required for crewed space missions in areas as diverse as go/no-go decisions, space-to-ground communications, space tracking, real-time problem-solving, and crew recovery. According to a story in the the New York Times following his death, Kraft’s expertise influenced global tracking and instrumentation networks, instruments to monitor the condition of astronauts, flight plans, emergency procedures, techniques for splashdowns and recoveries at sea, and the training programs for thousands of ground personnel.

Space Kraft: Christopher Kraft (standing), MSC director of flight operations, oversees activity at the flight director’s console in the mission operations control room on the first day of the Apollo 10 lunar orbit mission. (NASA)

Kraft retired in 1982, but his renown did not fade. NASA’s Building 30 Mission Control Center at Johnson Space Center is now the Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., Mission Control Center. The late Kraft donated his NASA documents and original flight plan papers to his alma mater. He encouraged his colleagues, including Michael Collins, former astronaut and command module pilot, to do the same. Kraft Drive on the Blacksburg campus bears his name.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Virginia Tech produced graduates who would play important roles in space.

There was John McKay ’50, a graduate of the aeronautical engineering program, who flew the North American X-15, an experimental spaceplane, to an altitude of more than 50 miles, qualifying him as an early astronaut by U.S. standards.

FLY HIGH: John McKay ’50 made 30 flights in the rocket-propelled X-15, including a 1965 mission in which he flew higher than 50 miles and reached the edge of space. McKay was posthumously awarded his astronaut wings in 2005.

Others, including C. Howard Robins Jr. ’58, Ph.D. ’67, and Robert Tolson ’58, M.S. ’68, Ph.D. ’90, supported the Apollo missions to the moon, the Viking project to Mars, and development of the Skylab space station.

Bill Piland ’62 spent 39 years at NASA in a series of leadership positions. He credits the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets for shaping his career.

Homer Hickam ’64 was an engineer at NASA’s Marshall Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, where he trained astronauts for high-level missions, including the Hubble Space Telescope mission. The New York Times bestselling author’s memoir, “Rocket Boys,” was the inspiration for the popular film “October Sky.”

PIONEER: Charlie Yates ’58 was the first Black graduate of Virginia Tech and a faculty member in the Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering.

Virginia Tech’s first Black student, Irving Peddrew, spent his career in the aerospace industry, while Charlie Yates ’58, the first Black graduate, was a faculty member in the Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering. Peddrew-Yates Residence Hall was named in their honor in 2002.

To The Moon And Back

During the 1960s, President John Kennedy’s support for the space race advanced opportunities for space-related education at Virginia Tech. NASA donated a wind tunnel for research, and the university also added two supersonic blow-down tunnels, a “plasma-jet,” an instrumentation lab, and its first analog computer.

Such examples clearly illustrate Virginia’s Tech’s early impact, yet they barely scratch the surface of the university’s contributions on the space flight industry. Numerous alumni filled crucial roles at NASA, at other public agencies, and in the private sector to increase humanity’s presence in space. Their experiences at Virginia Tech proved to be foundational in solving the challenges required for space flight, exploration, and research.

The first Hokie to cross the Kármán line, a 100-kilometer boundary internationally accepted as the threshold for becoming an astronaut, obtained his graduate degrees in physics at Tech. Roger Crouch M.S. ’68, Ph.D. ’71 flew as a payload specialist on two space shuttle flights in 1997, logging a combined 471 hours in space while conducting a variety of studies. He still remembers the thrill of the launch and orbiting the Earth once every 90 minutes.

Lift off: Charlie Camarda ’90 took a Virginia Tech flag on a shuttle into space and later presented it to the university.

“As we went south from Asia down toward Australia, I could see seven islands erupting that day with steam or smoke or something,” Crouch said. “It was just totally awesome. I thought, ‘Here’s a little ole hillbilly who in 45 minutes went from the west coast of Africa to Australia and saw marvelous things I never even imagined.’”

Eight years later, Charlie Camarda Ph.D. ’90 flew as a mission specialist aboard space shuttle Discovery—the first mission following the loss of the Columbia shuttle in 2003. Camarda spent his career at NASA focused on thermal engineering—controlling the high temperatures a craft can reach on its way to and from space. He holds seven patents based on his research.

Out-Of-This-World Opportunity

Through the remainder of the 20th century and into the new millenium, Virginia Tech continued to develop its aerospace and ocean engineering department while working to bring together students and faculty across varying disciplinary backgrounds.

Around 2005, Virginia Tech began to develop a formal space research and educational strategy within the College of Engineering. It was a partnership between the Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering (AOE).

In 2016, Kevin Crofton ’82 committed $14 million for what is now the Kevin T. Crofton Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering, along with $1 million dedicated to the university’s Division of Student Affairs. This gift helped to accelerate the progress of the space program.

SPACE GIFT: Kevin Crofton ’82, ’87 heads a global semiconductor and microelectronic device manufacturing company. His $14 million gift to the Kevin T. Crofton Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering at Virginia Tech accelerated the progress of the space program at the university.

“The education I received from Virginia Tech opened the doors to my entire career,” said Crofton, who worked in the aerospace industry for more than a decade, primarily on Boeing’s Inertial Upper Stage and as the boost motor program manager on the Standard Missile program. “Beyond the theory and empirical textbook learning,Tech’s engineering program exposed me to the art of using a data-driven situational analysis to problem solving, the opportunity to interact with people from various backgrounds in a team environment, and the understanding that a team with a common set of goals can achieve anything.”

Crofton now heads a global semiconductor and microelectronic equipment manufacturing company.

“On a purely personal basis, the AOE program taught me the value of perseverance,” Crofton said. “The reason for my donation to Virginia Tech is because I want to give others the opportunity to have the same experience that I’ve had in their own lives. I grew up in a heavily agricultural area of Southwest Virginia. Without my Tech experience, I’m not entirely sure what I would have accomplished in life. I want that legacy and message to be that, regardless of their personal circumstances, anyone can accomplish anything with a great educational background and perseverence. That I May Serve—this is the way I can embody Ut Prosim.”

Space@VT: (top) Ph.D. candidate Virginia Smith inspects a satellite in a clean room at the Space@VT workspace at the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center.

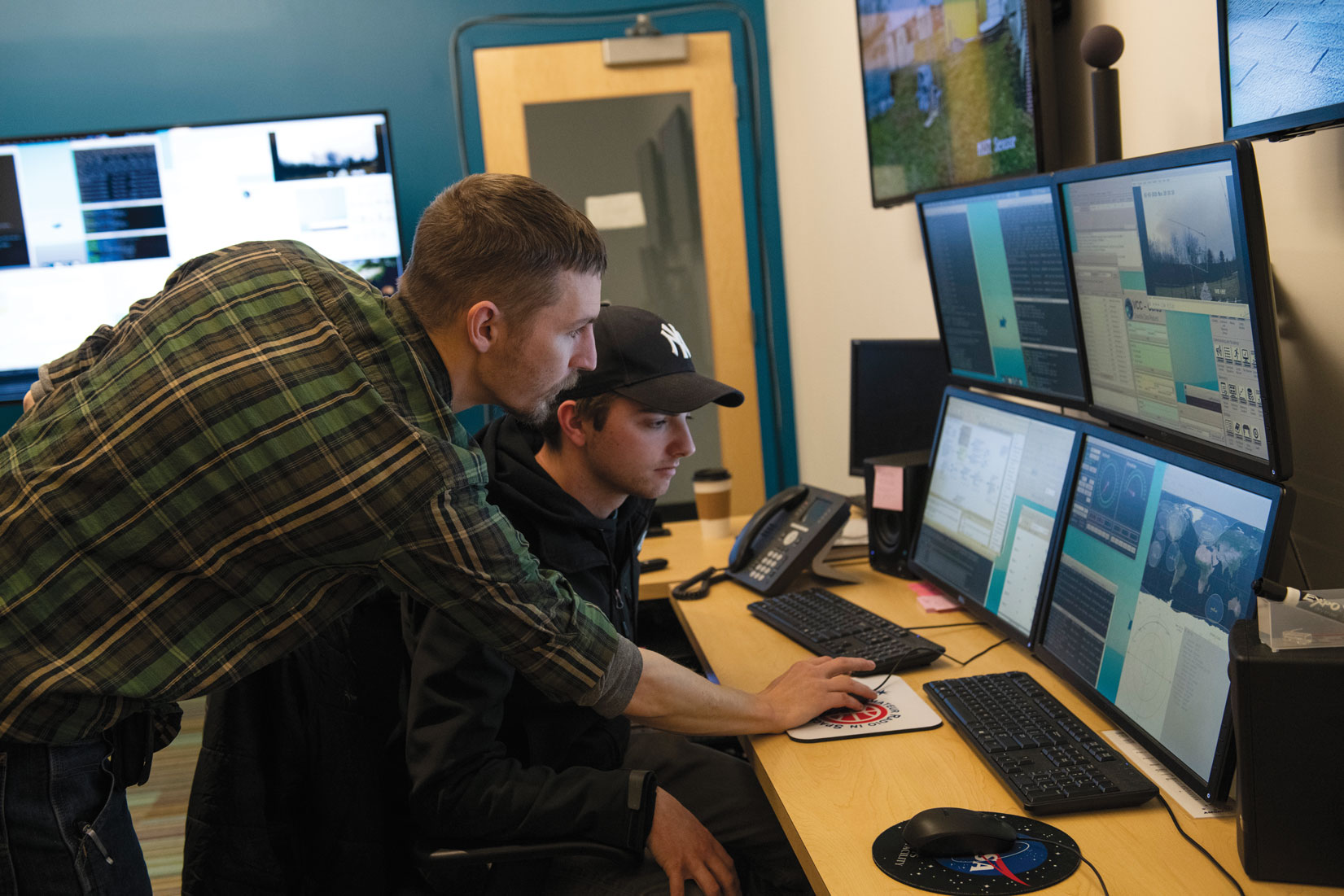

Zach Leffke, research associate, and Gavin Brown, a graduate student in aerospace engineering, track the cubesat constellation satellites as they pass over Virginia.

Since 2007, space research and education have resided in the Center for Space Science and Engineering Research (or Space@VT). The center is a result of a National Science Foundation award to establish university space research and educational programs. Space@VT, housed at the Corporate Research Center in Blacksburg, Virginia, is an internationally recognized space program, fostering space-related research throughout the university.

“Space@VT embodies a blend of basic science, engineering, and aerospace expertise,” said Wayne Scales, founding director of Space@VT and the J. Byron Maupin Professor of Engineering. “This is rare among university space programs.”

And, as the university advanced academic offerings and research, Virginia Tech graduates continued to shape space exploration at NASA and, increasingly, in the private sector.

Patricia “Pat” Remias ’85 strongly considered majoring in biomedical engineering, but during a classroom segment on human life support in space, she started to think more about aerospace. Now vice president of engineering for Sierra Nevada Corp.’s space systems business area, Remias said the strength of Virginia Tech’s academics combined with the university’s service ethic prepared her for a career in the aerospace industry. And she credits touring with the New Virginians musical group as a singer and dancer for developing the leadership skills and the ability to team with people from different backgrounds that would further her success.

“I wound up becoming dance captain in my final year in the group,” Remias said. “That, quite frankly, taught me more about the importance of presentation, leadership, and self-confidence than any other experience I had at Virginia Tech.”

CHASING A DREAM: Patricia “Pat” Remias ’85 is vice president of engineering for Sierra Nevada Corporation’s space systems business area. She stands before the Dream Chaser, a space utility vehicle that numerous Hokies have worked on since the early ’80s.

Sierra Nevada Corp. has been developing the Dream Chaser, a space utility vehicle that will conduct at least six cargo missions to the International Space Station beginning in late 2021. The Dream Chaser is based on a design that NASA drew from spy photos of a Soviet craft that splashed down in the Indian Ocean in 1982. Bill Piland worked with the project during his stint at NASA Langley, and so did Jill Marlowe ’88, whose first job at the center involved studying how people of all sizes enter and exit the craft. Now, Remias’ company is working with the design.

Marlowe, now Langley’s associate center director for technical, was drawn to Virginia Tech’s service mission and its welcoming, iconic campus. After an early-career job designing submarines, she transferred to NASA Langley in the 1990s. Marlowe served in various roles at NASA before advancing to her current position, which aims to not only identify the next wave of revolutionary space research, but also transform the way research is done in the digital age.

“We need to be working in ways that are much more connected and much more agile than we have in the past,” Marlowe said.

A key motivator for Marlowe’s job is oriented around NASA’s Artemis mission, which intends to land the first woman and next American man on the moon by 2024 as the foundation to eventually send humans to explore Mars.

“Artemis is challenging us to deliver breakthrough technologies on a very aggressive timeline, with a strong focus on mission infusion right from the start,” Marlowe said.

Artemis spacecraft

Brett Montoya ’12 contributes to Artemis from a different angle—as an architect designing homes for astronauts in space. “My job is pretty similar to what an architect does terrestrially,” said Montoya, a biology major at Virginia Tech who earned a master’s degree in space architecture at the University of Houston. “We design the spacecraft to accommodate all of the systems necessary to keep astronauts alive. There are quite a few more for a spacecraft than a house, and we make sure the environment we create is intuitive and comfortable for the users.”

Montoya leads a team of space architects and industrial designers at the Center for Design and Space Architecture at NASA. He also has been working with Virginia Tech’s College of Architecture and Urban Studies to recruit undergraduates who want to learn more about the career path and gain real experience. Montoya partners with faculty to offer students the option to pursue space-related design projects for their senior theses.

As Montoya demonstrates, the range of space-related studies has grown deeper and broader as the Space Age has matured. Space exploration has become a launchpad for innovative faculty and students to pursue a wide array of research that benefits the world in ways that have nothing to do with spaceflight itself.

Sean McGinnis, director of the green engineering program at Virginia Tech, has taught a series of green engineering short courses for NASA employees at nine different sites since 2011. NASA hired him to teach the three-day classes for employees interested in gaining a deeper understanding of environmental issues for their work in engineering, research, and operations. The curriculum offers overviews of environmental topics and highlights related implications in NASA’s work.

“A couple of decades ago, people were focused on what the mission was, but not on the broader environmental impacts across the mission life cycle,” said McGinnis, who will teach more courses this spring. “This training is about awareness, and it tries to build an internal culture of considering environmental impacts throughout the entire mission.”

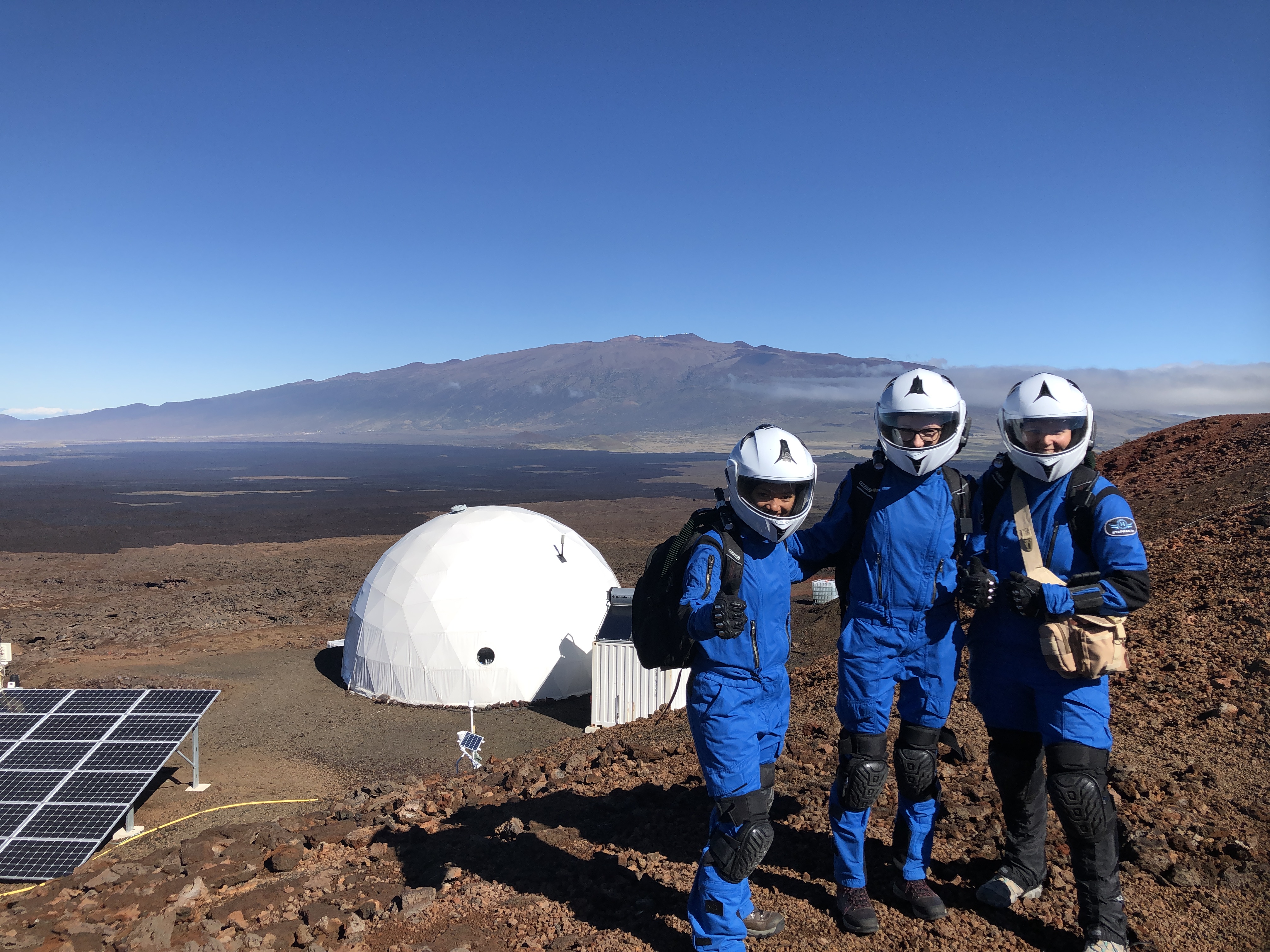

Another Virginia Tech graduate, Erin Bonilla ’04, is studying how astronaut crew members psychologically respond to living in space environments. In January, Bonilla was vice commander of a six-person, all-female crew who spent two weeks living as astronauts in a Mars-simulated environment. The SENSORIA mission, which was held at the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation solar-powered habitat in the Big Island of Hawaii, monitored how the crew’s mental and physical health were affected by the experience.

Life on Mars: Erin Bonilla ’04 stands with some of her crewmates in the SENSORIA mission outside of the Hawaii High Seas Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) habitat on the Big Island of Hawaii. Pictured, from left to right, are Makiah Eustice, Adriana Blachowicz, and Bonilla.

“There are few studies directed at women in the space environment,” said Bonilla, who lives in Arizona. She co-founded Flight Ready Systems, a consultancy specializing in field research, curriculum development, and educational outreach strategy with expertise in space-simulated environments. Bonilla’s research contributes to NASA’s long-duration spaceflight needs.

Bonilla’s fascination with the world of space began when she took a job managing websites for a contractor at NASA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. As she put her degree in graphic design from Virginia Tech to work, she also caught the “space bug.”

“Once you are into space, you want to learn more,” she said. “Working at NASA, you’re part of that family. You’re contributing to that greater mission.”

The Next Generation

Virginia Tech continues to prepare the next generation of Hokies for space work. Today, the university supports a host of student teams and clubs focused on space research and design, and many of these projects are funded through grants from NASA.

In January, several Virginia Tech graduate students and faculty traveled to Alaska’s Poker Flat Research Range to launch a sounding rocket built for NASA through Space@VT. The rocket’s purpose is to measure the accumulation of nitric oxide in the atmosphere as Alaska’s 24-hour darkness surrounds it. Ultimately, the team plans to assess how this gas moves into the stratosphere and destroys ozone.

That experiment sparked doctoral student Saswati Das’s interest in working with space and atmospheric science after graduation. “What captures my attention the most is the attempt to satisfy the human quest to know what lies beyond planet Earth through technology,” said Das, who spent a month in Alaska. “I realized how fascinating it is to see how several missions in the past have successfully uncovered what was for long unknown to mankind.”

Grace Wusk is another example of the next generation of Hokies in space. Wusk, a doctoral student who is studying biomedical engineering, grew up watching rocket launches on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Her parents work at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, so she had easy access to all things space at an early age.

Wusk interned at Langley Research Center and Johnson Space Center in Houston, and then brought her space fascination to Virginia Tech. Using a NASA fellowship, she is researching astronaut health and performance by simulating space walks. Wusk studies factors that impact the physiological state of an astronaut, such as heart rate variability, skin conductance, and brain activity, with a goal of building a model to predict astronauts’ cognitive states.

Space@VT sounding rocket launch

NASA work “can really inspire anyone,” said Wusk, who hopes to work for the agency eventually. “You see how much international collaboration there is. You don’t see borders in space. It’s very unifying.”

Space exploration and the resulting research have transformed everyday life through technology found in smartphones, running shoes, fire-resistant fabric, solar panels, and much more. But humanity’s endeavors to reach the outer realms also inspire us and bring us together.

“I literally watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon in 1969 on a little tiny Sony TV with a tiny antenna to bring in the signal,” remembered Kevin Crofton. “At that point, I was 8 years old. Well, I was just totally blown away by it. I immediately wanted to be an astronaut.”

And Jill Marlowe believes space exploration is capable of “bringing us together for humanity.

“One of the things the Apollo astronauts talked about was that there was really a sense of, ‘We did this. We, humankind, did this,’” Marlowe said. “The world needs some of that right now. Some of these big goals we go after, they have very human purposes at their core, and it’s bringing us together.”