COLLARED

TECHNOLOGY FOR THE BEST-DRESSED LEMUR

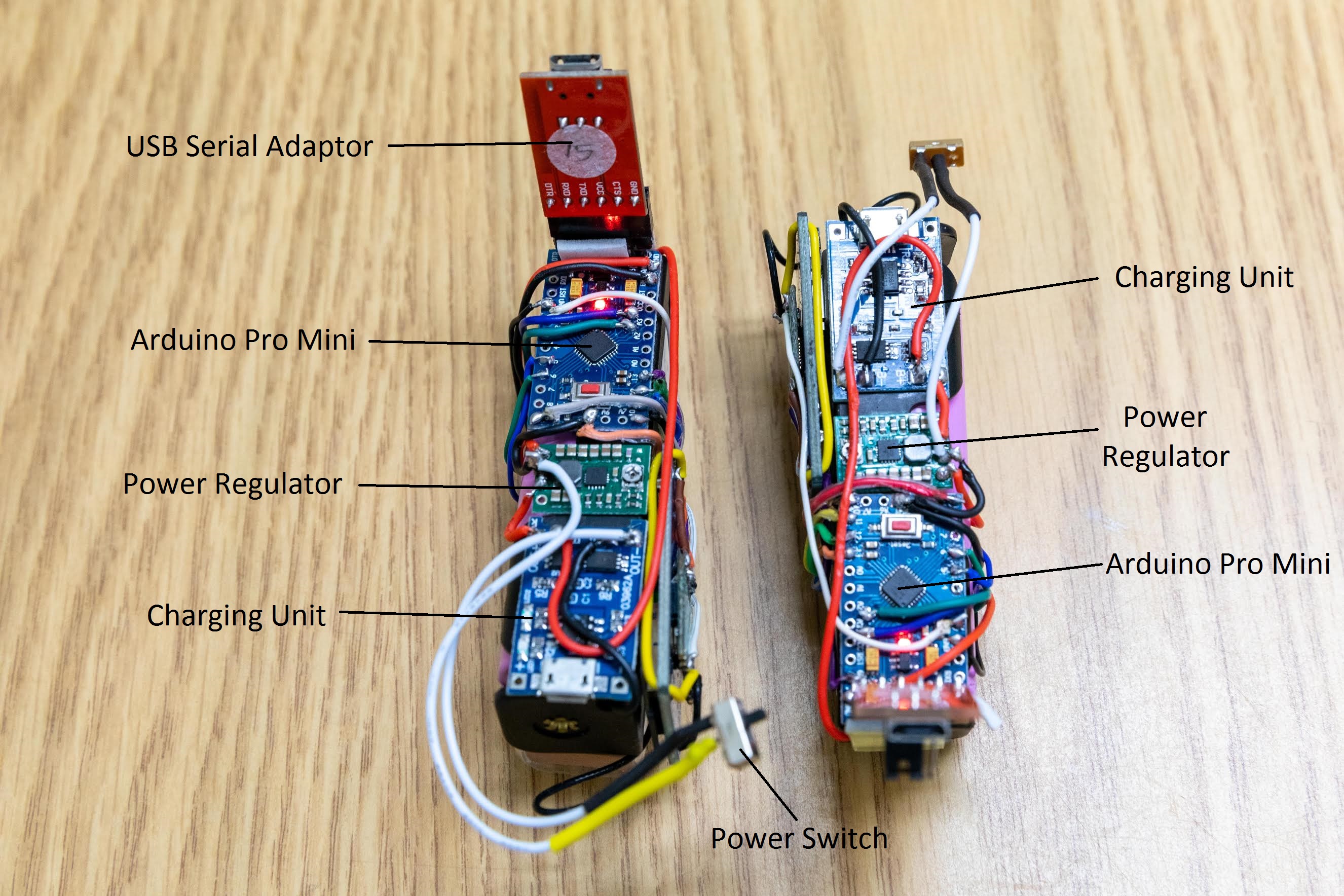

Wearable Computing: The Arduino Pro Mini is a microcontroller and essentially functions as the processor/“computer” on the lemur collar. Its function is to take inputs from other components of the collar (GPS, radio, accelerometer, etc.) and send signals to these components. Without it, the collar wouldn't be able to work.

A Virginia Tech graduate student is working to save an endangered lemur species in northern Madagascar, and a group of engineering students has stepped up to help make the project affordable. (Read about their activity in this issue.)

Meredith Semel, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Biological Sciences, along with a team of undergraduate students and Nicole Abaid, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics, are crafting unique, cost-effective collars to track the critically endangered lemurs.

“The purpose of the collars is to be able to understand lemur behavior, especially their movement patterns, without physically having to observe them,” said Semel.

Semel, who was named a National Science Foundation research fellow at Virginia Tech in 2016, studies Madagascar’s golden-crowned sifaka, a lemur species jeopardized due to deforestation and habitat loss. Abaid is an advisor for the seven undergraduate students who have helped create the collars that Semel will use to track the lemurs.

Parts is Parts: Charging unit: allows the battery to recharge when needed; Power regulator: used to regulate voltage level and it acts to protect the device from damaging power supply inputs; Power switch: turn the device off and on; USB serial adaptor: allows collar to charge during the testing process, using a micro USB cord. Once the collars are ready, this component will be removed.

Scientists often use tracking collars that cost thousands of dollars apiece to learn more about animal behavior, but Semel expects each Virginia Tech-designed collar to cost less than $200. This will allow the team to track more individual lemurs and to study them in different habitats.

Semel began the collar project assuming it would take two semesters. Three years later, she and her team have completed the prototype. The next step is to test the collars on captive lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center, a facility that houses the largest population of lemurs outside Madagascar. Their work will ensure that the collars are safe for future use on lemurs in the wild.

“A lot of wildlife are threatened due to climate change, habitat loss, disease, or overall human encroachment,” Semel said. “Being able to track them in a cost-effective way will allow us to understand their behavior, physiology, and habitat requirements and apply the data to conservation management plans.”

Haley Cummings, a senior majoring in public relations, is an intern with Virginia Tech. Emily Roediger, director of communications for the College of Architecture and Urban Studies, contributed to the story.

Around the Hokie Nation

- Building the Optimal Data Base

- Impact of Giving: Well Spent

- From Vine To Wine—Andy Beckstoffer—alumnus profile

- Dialed In—Tyler Henderson—alumnus profile

- Making a Cyber Difference—Jessica Gulick—alumnus profile

- What’s Important Now?—Bud Foster—profile

- Heavy Lifting—Shaun Hairston—alumnus profile

- In The Spirit Of Orange And Maroon—Mickey Hayes—alumnus profile

- What’s The Hype?

- Class notes

- Alumni shorts

- Alumni travel

- Retro

- Family

- Infographic

- In memoriam