|

by Su Clauson-Wicker

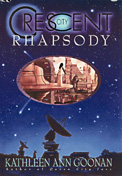

The proof is in her most recent science fiction novel, Crescent City Rhapsody, due out through Avon books in January. In it, a reclusive astrophysicist, who just happens to be tenured at Virginia Tech, finds his life endangered when his homemade radio antenna intercepts weird signals from outer space. Zeb Aberly's troubles are compounded by his unmedicated manic depression, which sometimes befuddles his perceptions but never his scientific integrity. Most of Zeb's adventures on the run occur in Washington, D.C., but before he slips off the Tech campus through a steam tunnel, the book calls up a litany of New River Valley sites: Angels Rest, Ironto, Pearisburg, Floyd, and U.S. 460. The psychic landscape and ethos of the 1970s that Goonan experienced around Blacksburg are revealed in Zebs hands-on, no-frills approach to technology, including his solar-powered tracking station. Zeb is not based on anyone at Tech, Goonan insists, although she thinks he slid into the setting very nicely. "Zeb started out as a woman in Hawaii and migrated to Southwest Virginia, where he made it known he had to be a man," she says. "Fictional characters can get quite independent." Now a novelist with four books to her credit, Goonan shuttles between homes in Lakeland, Fla., where her husband, Joseph Mansy (chemistry 74), is an emergency-room physician, and Plantation Key. Last year, her 1994 first novel, Queen City Jazz, was a finalist for Great Britain's highest award for science fiction. It, with her latest novel and Goonan's third novel, Mississippi Blues, form a nanotechnology trilogy. The basic premise of these and her second novel, The Bones of Time, is that using nanotechnology, almost anything can be created at the molecular level; evolution begins to run amok. "Queen City Jazz is nanotech seen up close from one persons point of view," Goonan says. "Mississippi Blues enlarges the frame. In it, I explore the conscience of a nation and try to show how the future I portrayed is rooted in Americas past and present," she says. "My study of American writers at Tech wasn't wasted." Crescent City Rhapsody begins 12 years from now and chronicles decades of tremendous social, economic, and technological change as old systems fail and nanotechnology gets started. A pregnant pause between technologies is how Goonan puts it. Science fiction is definitely a literature of ideas. "I love the questions you can ask," she says. Publishers Weekly, in fact, says: "Goonan explores serious questions with an intensity and skill that make her a major voice in the field." "In the past century, science has changed our idea of our place in the universe," Goonan says. "When I was at Tech, I took almost enough philosophy and religion courses to qualify for a double major because I thought they might answer the questions I had: What is happening? What is time, space, and consciousness? Why am I here? "I had no idea that science was working on these questions. The excitement that I now feel for science was not something I learned in school. It grew out of my own reading. To me then, science was the psychology department killing the rats that had learned to swim toward the green light instead of the red light, killing the rats rendered useless by their knowledge--a job that one of my roommates had. I didn't know that this research was laying the foundation for understanding brain function in humans. " Now Goonan regularly talks to scientists, who help her with technical aspects of her books--how to get a 200-pound bee to fly, for instance. She also subscribes to Nature and Scientific American and buys tons and tons of science books, most recently tomes dealing with the nature of consciousness, telecommunication, and nanotechnology. Shes also done a lot of reading on voodoo, jazz, Hawaiian culture, and entomology. "I like research. Maybe I do too much of it," she says. Ever since her Tech days, Goonan has taken a maverick, extremely focused approach to her education. "I really didn't go to classes much at Tech. I'd read the books and show up only for exams, unless the professor was a really great lecturers--as Virgil Cook and Guy Hammond were," she says. "I hid out from people during that period. I just sat in the library reading and writing with purple ink on onion-skin paper. I wrote all day. That was all I wanted to do." Mainly to avoid working for anyone else, Goonan says, she became certified as a Montessori teacher. She found she enjoyed the methods and opened her own elementary school in Knoxville, Tenn., where her husband was completing his medical residency. "Then one Saturday in May, my house was all clean and it was around my 32nd birthday; I realized that if I was going to be a writer, Id better start soon," she says. Writing three to five hours a day before and after school, Goonan completed what she calls her "trunk" novel--it's still in storage. Soon after that, her husband gave her the opportunity to write full-time when they moved to Hawaii. Goonan wanted to make money, so she tried her hand at confession stories--African American confessionals--but was turned down because the editor could tell she wasn't black. Goonan tried mainstream; she tried fantasy; she tried mixing the two, a big faux pas at the time. Then she hooked into a writers group of published science fiction writers. She didn't care that the group was known as the Vicious Circle or that she was the sole unpublished member; Goonan eagerly sought professional critique sessions. "I was the only one writing in this group, so when they finished with me, wed all play spades," she says. "The critiquing was really good for me. It was always fair. I sold every story they critiqued." One of her successful sales was The Snail Man, a story she wrote for Carroll Newman's English class in 1972. It was published by Strange Plasma on its 10th time out. Another move and a change to the novel form has made group critiques impractical, although Goonan says one loyal friend has read her finished novels. She's currently working on her fifth novel, Light Music, which will conclude her nanotech quartet. "Im not sure what I'll work on next," says Goonan. "I might try fantasy, maybe a mainstream novel." Science fiction has been provocative, but not lucrative, she says. "You might think that at a time when people are worrying about Y2K computer failure and the possible technological repercussions, that science fiction would be especially popular," she says. "But it's not. So many people aren't interested in looking further into the future these days. They think the future is already here." Not so, says the woman who mines her past to create a future where the dead are resurrected in cocoons of organic jelly, hormonal implants can be activated to cure a bad mood, and scientists construct luxury apartments by starting with a molecule. Back to Features Page |

Although Kathleen Ann Goonan (English 75) doesn't get back to Blacksburg much these days, the memories of her college stomping grounds are indelibly encoded in her brain cells.

Although Kathleen Ann Goonan (English 75) doesn't get back to Blacksburg much these days, the memories of her college stomping grounds are indelibly encoded in her brain cells.